Post-traumatic nightmares:

When death is the night watchman

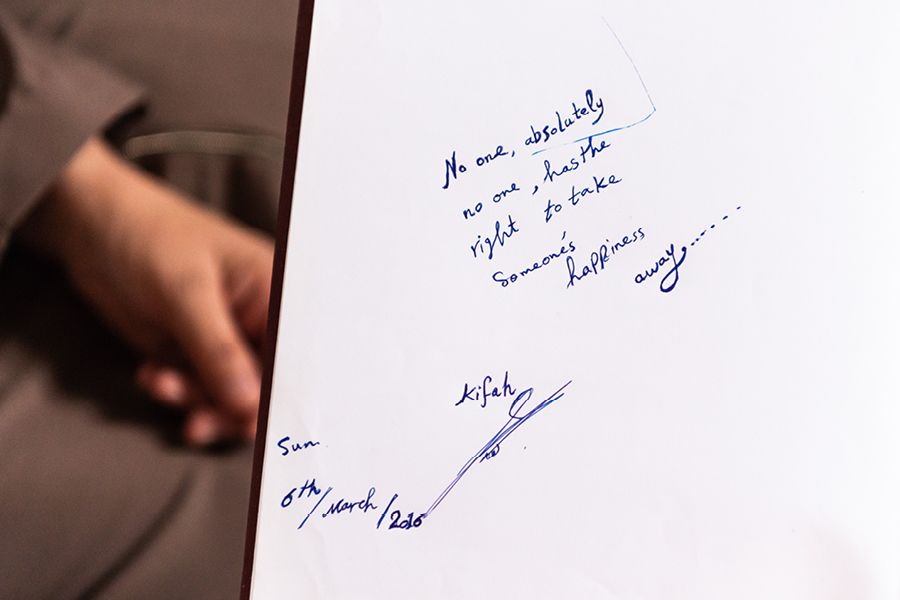

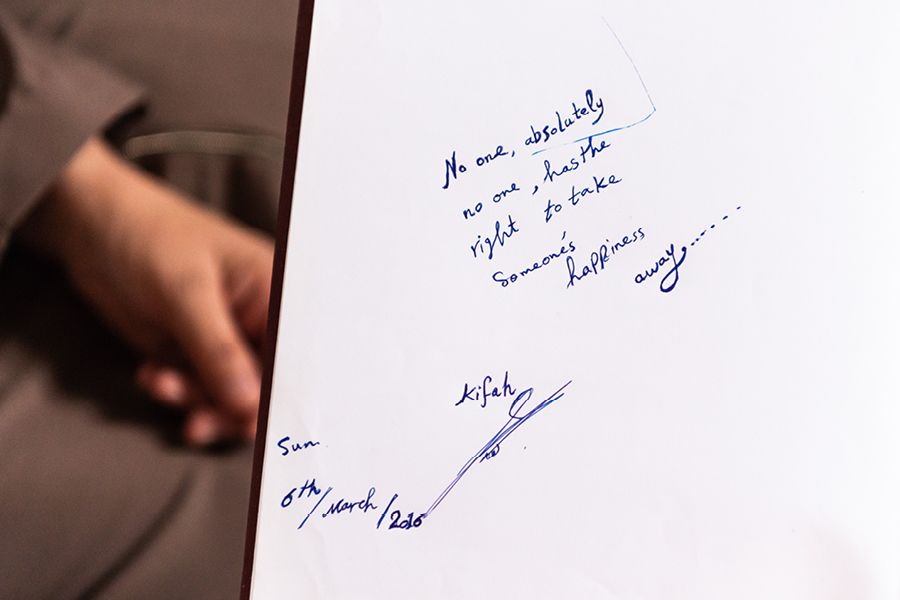

“There are painful memories in here. But the memories also make me remember what I have achieved,” says Kifah. She is one of a handful of Syrian refugees in Jordan who has a very special knowledge of trauma and stress treatment for children.

She has her hands on her notebook, as if to protect it. She says:

“I call the book ‘My stories’. I still look at it. And when I start leafing through the pages, I just want to read it all over again. Afterwards, it feels good to be able to close the book and put it away.”

The magical drawings: a child has drawn a terrible war event he has witnessed, which haunts his nightmares. The drawing shows a soldier firing a gun, houses on fire and planes dropping bombs. Later, after the BLP conversations, the child changes the drawing by replacing the scary content with something nice. Thus, the nightmare also disappears. See how the “transformed” drawing turned out, at the bottom of this article.

Kifah, 41, lives in a housing unit in one of the world’s largest refugee camps, Zaatari. The living room smells faintly of roses. The walls are light blue and there are potted flowers. Kifah’s three children, aged from 10 to 14, come in with Arabic coffee. “Made with love” is written on the coffee cups. The children also serve fruit, dates, fizzy drinks and chocolate. Kifah gently overlooks our repeated “no, but thank you very much – it’s too much”.

Subscribe to our newsletter to read more stories!

She picks up her book, and gently strokes the dark brown covers.

“There are painful memories in here. But the memories also make me remember what I have achieved.”

The magical drawings: a child has drawn a terrible war event he has witnessed, which haunts his nightmares. The drawing shows a soldier firing a gun, houses on fire and planes dropping bombs. Later, after the BLP conversations, the child changes the drawing by replacing the scary content with something nice. Thus, the nightmare also disappears. See how the “transformed” drawing turned out, at the bottom of this article.

The magical drawings: a child has drawn a terrible war event he has witnessed, which haunts his nightmares. The drawing shows a soldier firing a gun, houses on fire and planes dropping bombs. Later, after the BLP conversations, the child changes the drawing by replacing the scary content with something nice. Thus, the nightmare also disappears. See how the “transformed” drawing turned out, at the bottom of this article.

The children told Kifah terrible stories from the war. And perhaps it was easier for them to talk to Kifah than to someone else, because she had experienced the war herself.

The children told Kifah terrible stories from the war. And perhaps it was easier for them to talk to Kifah than to someone else, because she had experienced the war herself.

“Master instructors”

As an adviser in the Better Learning Programme (BLP), Kifah helped the war-traumatised students open up. For the first time, they managed to put into words the terrifying darkness that filled their thoughts.

The children told Kifah terrible stories from the war. And perhaps it was easier for them to talk to Kifah than to someone else, because she had experienced the war herself.

These are some of their memories:

One had seen an uncle thrown at an electric fence. Another child witnessed a family member first killed and then thrown onto a railroad track. One saw a family member have his hands cut off. And yet another saw his friend killed by a bomb on the way to school.

Kifah explains:

“These terrible memories returned as post-traumatic nightmares. For the children, they not only led to lack of sleep and difficulty concentrating at school, but also to stress, anxiety and a feeling of despair.”

“We who were trained to help the students knew that we could never make them forget their traumatic experiences from Syria. But, we could teach them how to live with those experiences.”

Kifah and her colleagues have helped 2,906 children in the Zaatari and Azraq camps in Jordan. The programme is considered short-term therapy. With a little effort, you can achieve a significant positive outcome. Studies from the Middle East show that children go from having five nightmares a week to just one. More than half stop having nightmares at all.

Professor of educational psychology at the University of Tromsø and expert on trauma, Jon-Håkon Schultz, is sitting in a car, driving through the golden desert. The goal of his journey is to meet Kifah and the other refugees he trained back in 2015.

Professor Jon-Håkon Schultz has returned to Zaatari refugee camp to learn from the BLP counsellors he once trained. He is collecting data for further research.

Professor Jon-Håkon Schultz has returned to Zaatari refugee camp to learn from the BLP counsellors he once trained. He is collecting data for further research.

“We call these advisers ‘master trainers’. First, we trained six advisers. I followed them up for three years. Since then, we have trained more. I planned to visit them earlier, but was prevented by the pandemic,” says Schultz, who has had a meeting with Kifah on Zoom.

Now, he wants to systematise their knowledge and experiences. He’s going to revise the BLP manual – for the third time.

“Kifah and the others have gained completely unique experience. There are few psychologists in Norway who have as much insight into these matters as they do. I would go so far as to say that they have the most specific experience with post-traumatic nightmares in the world.”

Life as a refugee

Kifah was an English teacher in Syria for ten years. She lived in a village in the province of Dara’a, just a few kilometres from the Jordanian border.

The capital of the province is also called Dara’a, and is considered the place where the Syrian uprising began in March 2011. The province was long controlled by armed groups and repeatedly attacked by government forces. Just a few months ago, the area was again affected by armed conflict.

On 15 April 2013, Kifah left Syria with her husband and children. They fled across the border into Jordan.

“My husband actually wanted to stay in Syria,” says Kifah, who is currently taking care of their three children by herself. Her husband travelled to Europe a few months ago.

“The plan is that he will find work and that we will follow him later,” she says. “He’s not coming back. I’m worried about the future.”

Kifah’s husband has travelled to Europe in the hope of finding work and creating a better future for his family. The photo has been anonymised.

Kifah’s husband has travelled to Europe in the hope of finding work and creating a better future for his family. The photo has been anonymised.

Trauma in Zaatari

Kifah and her family settled in Zaatari, which today is one of the world’s largest refugee camps. It was established in 2012 and was initially a small tented camp in the middle of the desert – because it was only supposed to be a temporary solution for the Syrian refugees.

It is raining and the streets of Zaatari refugee camp are empty.

Since then, Zaatari has grown into a large settlement, with housing units, high streets, shops and workshops. Here, families live year after year. Here, the old die. Here, new people are born – children who don’t know any other life than this. Today, 80,000 Syrians live in Zaatari.

Fences in Zaatari refugee camp.

Jordan has received more refugees than most other countries. As of December 2021, it had received more than 672,000 Syrian refugees, according to UN figures. The majority live in poverty, and are heavily reliant on humanitarian aid.

Having to live their lives behind high fences, in poverty, and with few or no future prospects, is in itself something that triggers trauma. It has also not helped that the schools in the camps – and in the country in general – have been closed due to the pandemic.

It is raining and the streets of Zaatari refugee camp are empty.

It is raining and the streets of Zaatari refugee camp are empty.

Fences in Zaatari refugee camp.

Fences in Zaatari refugee camp.

“No-one, absolutely no-one, has the right to take someone’s happiness away,” Kifah wrote in her book.

“No-one, absolutely no-one, has the right to take someone’s happiness away,” Kifah wrote in her book.

“The trauma programme was really new to me. The relaxation exercises we did during the training made me laugh – they seemed so childish in their simplicity,” Kifah says with a little laugh.

“The trauma programme was really new to me. The relaxation exercises we did during the training made me laugh – they seemed so childish in their simplicity,” Kifah says with a little laugh.

“I often had anxiety attacks with fainting, even after I came to Zaatari,” she says.

“I often had anxiety attacks with fainting, even after I came to Zaatari,” she says.

Striking gold

Before being introduced to the Better Learning Programme, Kifah had taken several health courses under the auspices of aid organisations working in Zaatari. Her husband, who was also a teacher back home in Syria, worked for a while for Doctors Without Borders in the camp. Kifah herself applied for a temporary position with NRC.

“No-one, absolutely no-one, has the right to take someone’s happiness away,” Kifah wrote in her book.

“The trauma programme was a new thing for me. The relaxation exercises we did during the training made me laugh – they seemed so childish in their simplicity,” she says with a little laugh.

“But the exercises worked! They did make me calmer.”

“The people we picked out among the Syrian refugees in the camps had either a teaching background or experience of psychological work. We were very happy when we ‘found’ Kifah. It was like striking gold,” says Jon-Håkon Schultz, and adds:

“That the refugees received this training from NRC gave them a purpose in life. It meant a lot to them to be in a position where they could help so many traumatised children. For the counsellors, it was a life-changing experience.”

“The trauma programme was really new to me. The relaxation exercises we did during the training made me laugh – they seemed so childish in their simplicity,” Kifah says with a little laugh.

Help for self-help

After each conversation with the children in Zaatari, Kifah wrote down her own thoughts and feelings.

“I myself had been traumatised as a result of the war. In Syria, I was very scared. Villages were bombed. People were killed. Homes were destroyed – our own house is just rubble. I was so fond of our house.”

Kifah takes out her mobile phone. She flips through her photo archive until she finds a picture of the ruins.

She says that when she uses the exercise where you close your eyes, breathe calmly and think of a nice, safe place, her safe place is her house as it once was.

“I often had anxiety attacks with fainting, and they continued when I came to Zaatari,” she says.

“I often had anxiety attacks with fainting, even after I came to Zaatari,” she says.

“I struggled with anger and aggression. But never violence. Anyway – it naturally affected my family.

The good thing is that working with the programme had a positive impact on me. My whole way of being changed. And why did that happen?

Well, when I heard the children talk about their own experiences, it made a great impression on me. They trusted me. I felt responsible for them. So, I had to find peace in myself. This also affected my home life.

Things got better.

Sceptical parents

Kifah recalls that they first had to ask the parents for permission before talking with the children.

“They said: ‘Do you think my child is crazy?’ Unfortunately, there is a lot of stigma around mental health. It’s a pity, because there are many who are struggling with mental stress due to the war.

The group discussion brought back memories of loss in her own family for one of the counsellors. She started to cry, and left the classroom to take a short break.

“But it helped that we had parent meetings where we could inform them about our programme. Not only that, but the parents saw that their children eventually got better. The parents even came to us and asked to talk because they also needed help.”

What are post-traumatic nightmares?

“A normal nightmare is when you have a bad dream, wake up and feel a little scared. With trauma-related nightmares, you think you are going to die – either by being very threatened, or witnessing others being threatened or dying. You are taken back there, in a way. You wake up – and then you’re there – in the middle of an incident that may have happened two years ago. And then your body becomes pumped so full of stress hormones that you have problems falling asleep again,” explained Jon-Håkon Schultz in a previous interview with NRC.

You can compare it to anxiety in a bubble. If you don’t puncture that bubble, the post-traumatic nightmares live their own lives and steal your energy.

The counsellor is comforted by an NRC staff member. After a while, the counsellor returns to the classroom and participates in the conversation.

Through the Better Learning Programme, we manage to change children’s post-traumatic nightmares, which leads to massive change in their lives. It’s almost like helping the blind to see.

The group discussion brought back memories of loss in her own family for one of the counsellors. She started to cry, and left the classroom to take a short break.

The group discussion brought back memories of loss in her own family for one of the counsellors. She started to cry, and left the classroom to take a short break.

The counsellor is comforted by an NRC staff member. After a while, the counsellor returns to the classroom and participates in the conversation.

The counsellor is comforted by an NRC staff member. After a while, the counsellor returns to the classroom and participates in the conversation.

Jon-Håkon Schultz has discovered that something very special has happened during the years that NRC’s trauma counsellors have been working in Jordan.

Jon-Håkon Schultz has discovered that something very special has happened during the years that NRC’s trauma counsellors have been working in Jordan.

Schultz describes the method used by Kifah and the other advisers:

Jon-Håkon Schultz has discovered that something very special has happened during the years that NRC’s trauma counsellors have been working in Jordan.

“We sit with the child and talk about the nightmare. And for many children, it is the very first time they have talked about it. We do it in a way that feels safe. In that way, we take away some of the fear. The nightmare becomes less scary.

“We look at elements of the nightmare, and ask the child: is there anything that can be made less frightening? To start with, the child almost always answers: ‘No, it’s not possible.’ But it doesn’t take long before they begin to see that it is possible.

“We ask the children to draw their nightmare. Then we ask them to change something in the drawing. For example, we might say: ‘There are many dark colours here – can we change any of them?’ And we keep going: ‘Can we remove that tank there and rather change it into a car? Can we take away that man in uniform and put in another man instead?’

“This is how we reduce the intensity of the nightmare. Or it might go away entirely. After a while, the child will usually say something like: ‘I had a nightmare last night, but I wasn’t afraid.’

“In addition to talking with the children, we give them advice on new bedtime routines. For example, they should think of a nice, safe place. Or of the new drawing of the nightmare, with the positive ending that they gave it.”

Before...

...and after receiving help from the Better Learning Programme.

Before: the trauma nightmare is expressed in the drawing.

But after the child gets help to cope with the nightmares, the drawings become bright and happy.

Before: bombs are falling from the sky and people are scared.

After: the bombs have turned into a shower of roses.

What is Better Learning?

Professor Jon-Håkon Schultz at the University of Tromsø in Norway has collaborated with the Norwegian Refugee Council (NRC) to develop the Better Learning Programme (BLP). The programme aims to help children and young people affected by conflict to process stress and trauma so that they can benefit from education. In 2012, BLP was implemented throughout NRC’s programmes in the Middle East. Since then, it has also been introduced in our programmes in Iraq and Myanmar. In 2022, BLP will be established in 27 of the countries where NRC works.

The Better Learning Programme has also evolved into pure research: Schultz collaborates with researchers at the Murdoch Children’s Research Institute in Australia and the University of Philadelphia in the United States.

Better Learning is based on five principles designed to help participants process trauma:

1: Being able to calm down

2: Having a sense of safety and stability

3: Having the power to change the situation

4: Connecting with others

5: Re-establishing hope

The programme is divided into three modules:

BLP I: A general, classroom-based psychosocial support approach encompassing all children and young people

BLP II: Instruction and psychosocial support for small groups of children who experience reduced concentration and learning ability

BLP III: A specialised, clinical approach to address nightmares, which many children experience as chronic symptoms of post-traumatic stress

The conversation offers both laughter and seriousness.

The conversation offers both laughter and seriousness.

They “cheated” a little

According to Jon-Håkon Schultz, psychologists will usually say that a prerequisite for being healed from a trauma is that you must be exposed to the pain that happened. You have to push through the pain. You have to talk about the worst things.

The conversation offers both laughter and seriousness.

And this is what happens, systematically, from beginning to end. The first time, your heart beats faster and you become stressed. Then, gradually, you have fewer and fewer strong reactions.

The Better Learning Programme is also based on this theory.

But Schultz has discovered that something very special has happened during the years that NRC’s trauma counsellors have been working in Jordan:

Some of the BLP counsellors in Zaatari refugee camp.

Some of the BLP counsellors in Zaatari refugee camp.

“We see that our advisers have ‘cheated’ a little. They don’t quite do what they have been told to do according to the manual: they don’t focus as much on the painful experiences. But they have achieved the same or equally good results! You could say that the ‘medicine’ has become a little milder. Before, we would ask: ‘What happened?’ Now we ask: ‘What do you dream about?’

“The psychology of this is that you can – by making a new drawing – CHANGE the dream. You can manipulate the dream.

“You can take control.”

The BLP app

“NRC operates in many conflict-affected areas. A common problem that we encounter is that we can’t reach those we are helping, for various reasons, whether they are teachers or students. That is why the BLP app is useful,” says education specialist Fabio Mancini.

The Better Learning Programme app.

The Better Learning Programme app.

“When I worked for NRC in Myanmar in 2018, we offered a support programme for BLP teachers to boost their competence. This included activities that involved physical meetings. But there was a problem: because NRC operates in conflict-affected areas, it was often difficult to reach teachers. The idea to create an app came as a direct result of these challenges,” explains Fabio Mancini, who currently works for NRC in Jordan.

“We worked in quite remote areas, where it was often difficult to connect to the internet. It was important to create an app that could work offline.

“We wanted the app to help teachers update and maintain the knowledge they had acquired during personal training. It also included easy-to-use exercises such as breathing exercises and relaxation techniques.”

The design, both in terms of structure and content, was created in consultation with the teachers. After the pilot project, the app was evaluated by teachers and Professor Jon-Håkon Schultz.

NRC’s Fabio Mancini is the man behind the BLP app.

NRC’s Fabio Mancini is the man behind the BLP app.

“We looked at the content, to see if it was relevant. And technically: was the app easy to download? Did it take a long time to download video content? Were there any restrictions related to different types of mobile phones? Then we asked: how did the teachers use the app? And when did they use it?” says Mancini.

“All this was important to consider when the app was to be updated.”

Recently, a new version of the app was released. It has now been adapted for use by the students themselves. During the pandemic, the app became a useful aid when children couldn’t go to school. It supported them through exercises and techniques that provided routines and structure for their homework as well as psychosocial support – making a difficult situation a little easier.

Azraq:

Old and new traumas

In Zaatari, the trauma programme was recently put on hold because it is no longer needed. In Azraq refugee camp, on the other hand, there is a need. There are currently 39,000 Syrian refugees living there, according to UN figures.

The fenced-in Azraq camp was established in 2014, and refugees continued arriving here until 2017. Then, the border was closed.

The camp is divided into several villages. Refugees who wish to leave the camp must first obtain a special permit. Those who leave without a permit risk being caught by the police and sent back to the camp.

BLP advisers Alaá, Kefaá, Faisal and Asma work in Village 5.

They have settled down in the shade to talk about how to help children who have seen and experienced terrible things.

They have settled down in the shade to talk about how to help children who have seen and experienced terrible things.

Jon-Håkon: “Congratulations – you’re doing a great job. How is it going?”

Alaá: “There are still children here who remember the war.”

Through a collective effort, pain can be expelled.

Faisal: “Yes, and they remember images more than anything else. We see more of that now than we did before the pandemic.”

Asthma: “It’s not just the war. It is also their life situation. The children see themselves trapped in a black darkness. Some have nightmares because of family conflicts. They dream that they are being kidnapped, killed. They also see death in relation to car accidents. I know of many who struggle with involuntary urination.”

Faisal: “One child experienced a housing unit burning down, and many are afraid that it will happen again. Fires and accidents trigger nightmares.”

Each drawing tells a story of the gruesome images that have invaded a child’s mind …

Asma: “Jon-Håkon, we are focusing on children in fifth and sixth grade here. Can the programme be used for older children as well?”

Jon-Håkon: “Yes! And that’s a very good question because we find that the older you are, the worse the nightmare.”

Alaá: “Everyone here needs support.”

Jon-Håkon: “When you have first have post-traumatic nightmares, they tend to stay.”

Asma: “We are happy with the BLP programme. It helps and protects the children. We know ourselves how the children feel.”

Alaá: “Before I learned about BLP, and a student behaved inappropriately, I didn’t understand what was going on in the child’s head. But now I know that every child has their own story. All children need someone to trust.”

… and about how the child has managed to transform the gruesome into something beautiful.

Asma: “Hearing the children’s stories made us stressed, too. NRC’s BLP expert Cristian De Luca had follow-up conversations with us afterwards. And that was a big help.”

Jon-Håkon: “Yes, it is important. You also need support because you are dealing with children suffering from trauma.”

Faisal: “I am very happy that I had the chance to meet you again and I look forward to our next meeting. I appreciate working with the kids. I want us to revise the manual so that we can include more age groups in the future.”

Jon-Håkon: “I’ll be back in a few months.”

Alaá: “We are strong. We’ve been through a lot. Thank you, Jon-Håkon, for caring for us and our children.”

Jon-Håkon: “Their children are also our children.”

Through a collective effort, pain can be expelled.

Through a collective effort, pain can be expelled.

Each drawing tells a story of the gruesome images that have invaded a child’s mind …

Each drawing tells a story of the gruesome images that have invaded a child’s mind …

… and about how the child has managed to transform the gruesome into something beautiful.

… and about how the child has managed to transform the gruesome into something beautiful.

And this is how the drawing at the top of the article turned out! The soldier has become an ordinary man holding a flower. Bombs have become flowers, the plane is a house (or maybe a colourful rocket with a bird on top?), the children are playing with a ball, and it is sunny. This is how the child regains hope.

And this is how the drawing at the top of the article turned out! The soldier has become an ordinary man holding a flower. Bombs have become flowers, the plane is a house (or maybe a colourful rocket with a bird on top?), the children are playing with a ball, and it is sunny. This is how the child regains hope.