“The new normal”

Aid work on the frontline

War and violent conflict have forced more than 80 million people to flee their homes in search of a safe haven. Many end up trapped in conflict areas that are difficult for aid workers to reach. Their situation is desperate.

This has become “the new normal” for thousands of communities caught up in conflict, and the aid workers looking to help them, according to Sarah Kilani, global access manager with the Norwegian Refugee Council (NRC).

“This has sadly become part of our daily lives in most of the countries where we work. Humanitarians in highly volatile environments face a wide range of challenges,” says Kilani,

In humanitarian language, these environments are described as “hard-to-reach”: places where political, bureaucratic, physical and security constraints prevent people from getting the help they need.

NRC supports refugees and displaced people in over 30 countries around the world. Support our work today.

Here are nine things you should know about the lives of those trapped in conflict areas and those who are trying to help:

#1

One in three countries

has restricted access

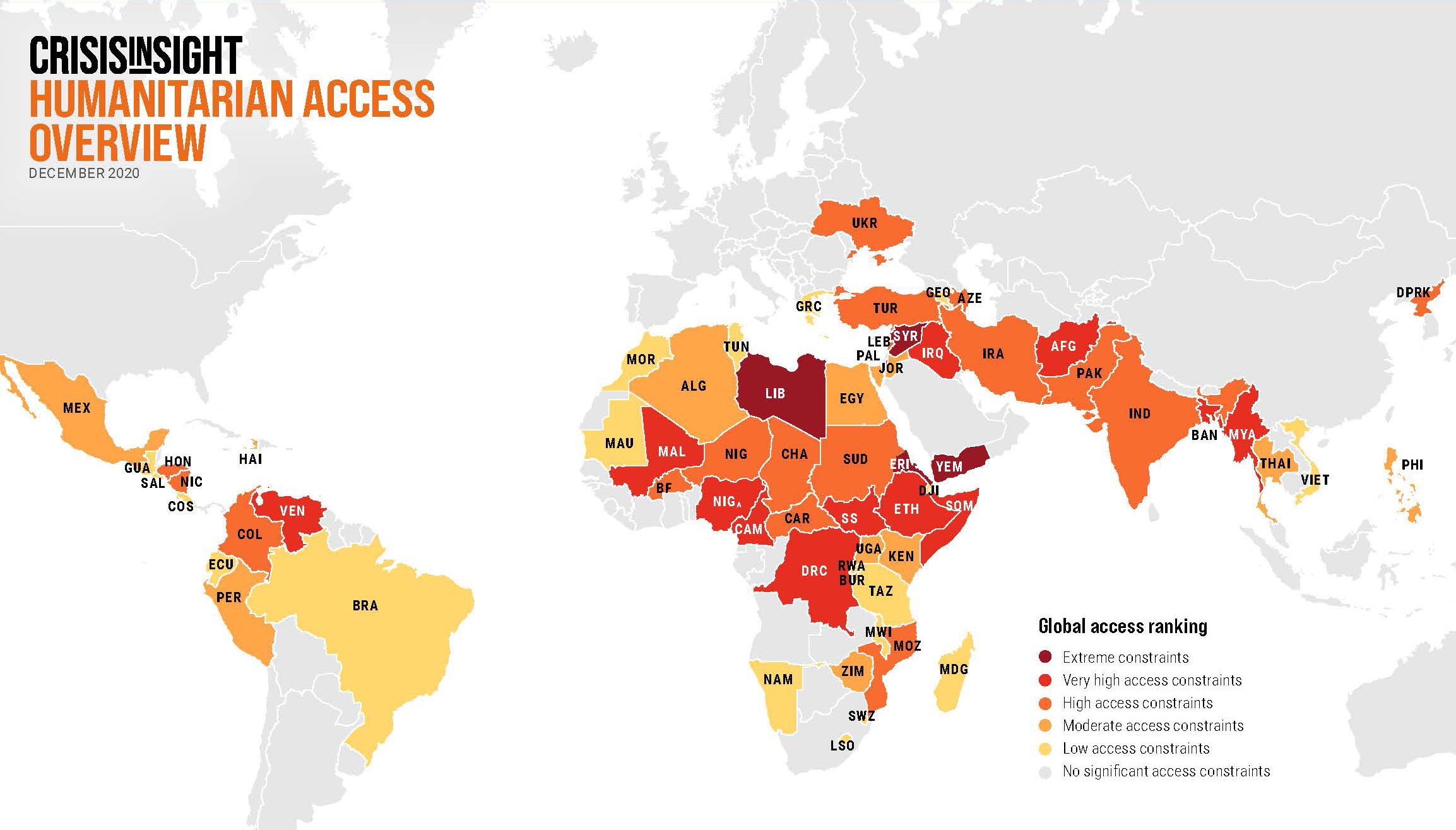

Crisis-affected populations in more than 60 countries are not getting the humanitarian assistance they need because the places they live are hard to access.

ACAPS, an organisation specialising in humanitarian analysis, has made an overview of the most challenging areas to access.

“Data from July to December 2020 has shown that there is a significant deterioration in the humanitarian access situation in Cameroon, Ethiopia, Honduras, Libya, Mozambique, and Nicaragua,” says Caroline Draveny, head of support at ACAPS.

“In this report, we have also taken into account that Covid-19 containment measures have heavily impacted access to aid across the globe."

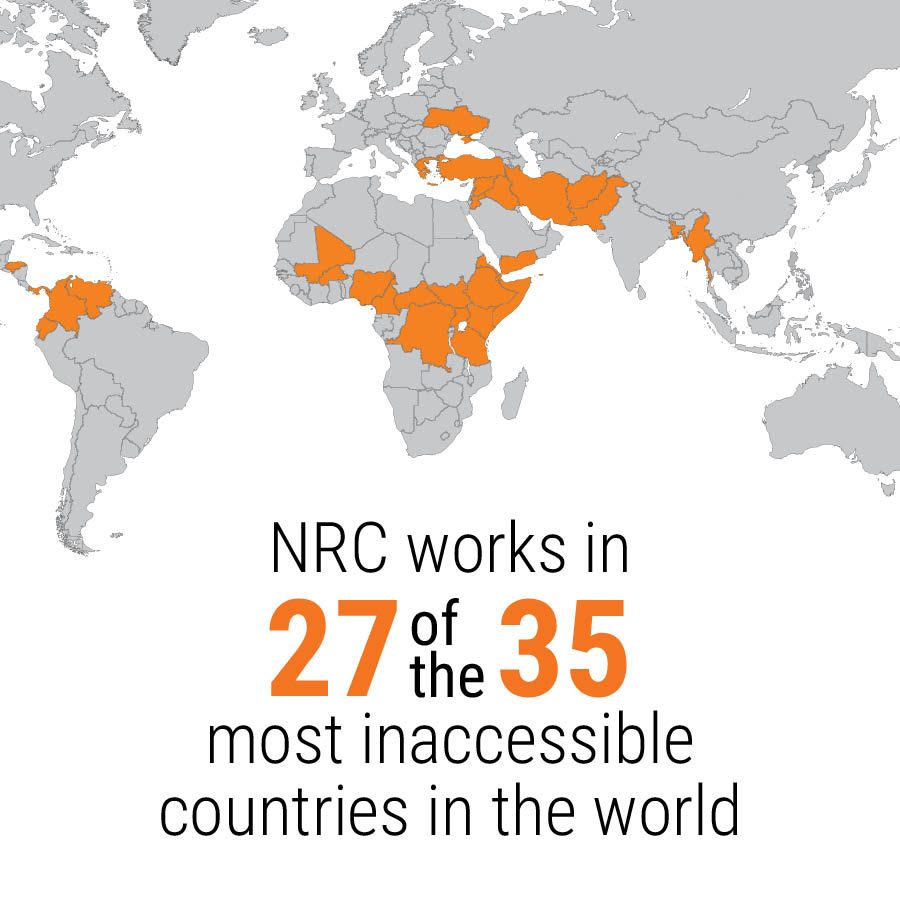

In 2021 NRC worked in 27 of the 35 most inaccessible countries in the world, including the top four: Syria, Yemen, Libya and Eritrea.

This story was first published in January 2021. Figures from ACAPS are from December 2020.

#2

Civilians are paying the price

In Syria, Farrah is a displaced mother of six children. This is how she described the situation in Idlib when we talked to her in February 2020.

Civilians often end up caught in the crossfire between warring parties, which frequently show disrespect for international humanitarian law. Residential areas are affected by direct acts of war and civilian structures become military targets.

“The NRC has provided assistance to displaced people for 75 years. Never have so many people needed help, and never before have the challenges of reaching out with aid been so great.”

Humanitarian access has two elements: the ability of people in need to access aid, and the ability of humanitarians to reach them.

Some areas of north-west and north-east Syria remain completely inaccessible for humanitarian organisations.

In Yemen, conflict across the country continues to disrupt people’s access to markets and services. This causes difficulties for aid workers delivering assistance.

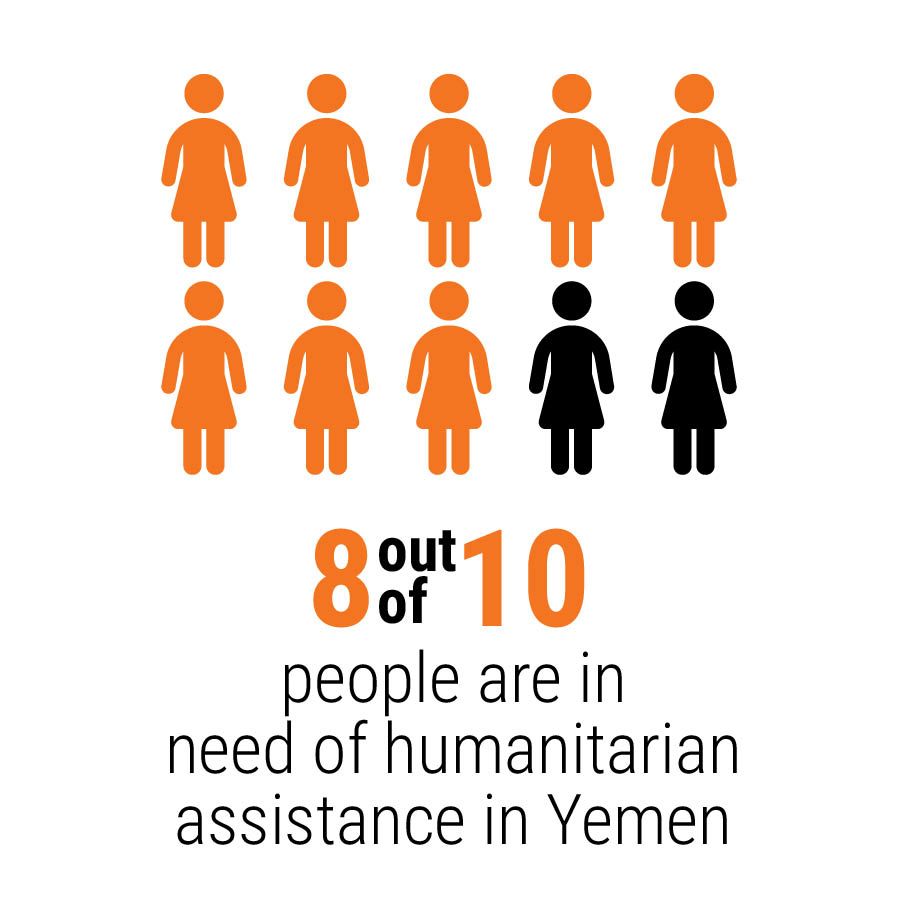

The crisis in Yemen

The war in Yemen, which began in 2015, has resulted in a severe humanitarian crisis, At least 18,557 civilian casualties were reported between March 2015 and November 2020, and up to 4.3 million people were forced to flee their homes. An economic downturn has left more than 24.3 million people (80 per cent of the population) in need of humanitarian assistance

.

#3

Aid work can be highly dangerous

Where armed groups, checkpoints, airstrikes and other dangers are present, humanitarian operations are affected.

Aid work in these areas is challenging and sometimes impossible. Even with adequate resources, it would only be possible to reach a minority of people in need.

In Yemen, landmines, airstrikes and a lack of food and medical help are putting thousands of lives at risk. And delivering aid is no easy mission.

“When driving a car in Yemen’s conflict-affected areas, even the sky above you and the very ground you’re driving on are possible threats. Fastening your seatbelt is minor compared to the many other precautions that have to be taken.”

“When driving a car in Yemen’s conflict-affected areas, even the sky above you and the very ground you’re driving on are possible threats. Fastening your seatbelt is minor compared to the many other precautions that have to be taken,” says Mohamed Abdi, NRC’s country director in Yemen.

On certain routes our cars have a large NRC logo on the roof, clearly visible from above, to reduce the risk of being hit by airstrikes. However, in areas with a high risk of carjacking, we have to ensure our cars are unbranded.

“Drivers must always keep to the main road, or, when off-road, follow the tracks made by other vehicles. The reason is simple: on a regular basis, cars and people are blown to pieces by landmines or unexploded bombs buried in the sand,” says Abdi.

#4

Emergency aid has

become politicised

The four guiding principles of humanitarian work – humanity, neutrality, impartiality and independence – underpin NRC’s approach and that of other aid agencies around the world.

In addition, frameworks such as International Humanitarian Law provide a basis for warring parties to allow humanitarian access during armed conflict.

These principles and frameworks are increasingly coming under threat, however. States and armed groups have created unfavourable conditions and obstructions to safe access in some areas.

“We see that state and

non-state actors can have a huge effect on our ability to reach people.”

“We see that state and non-state actors can have a huge effect on our ability to reach people,” says Kilani.

“They can hinder or deliberately obstruct access in many places through travel restrictions or excessive documentation requirements. Slowing down or blocking administrative processes means we struggle to reach people as quickly as is needed.”

#5

Counterterrorism can be counter-productive

Problems are not always limited to the countries where we work. A report from NRC shows that the international response to counterterrorism can restrict the ability of aid agencies to remain independent.

“Counterterrorism measures and sanctions can limit the ability of humanitarian organisations to engage with non-state armed groups and to negotiate access,” says Kilani.

In January 2020, outgoing US Secretary of State Mike Pompeo announced that he would be designating the al-Houthi movement, one of the warring parties in Yemen and officially called Ansar Allah, as a terrorist organisation. However, in February, the US government announced that it intended to revoke the designation.

“We welcome the decision by the US government to revoke these designations, which would have had catastrophic humanitarian consequences and hampered our ability to get food, fuel, medicines and aid into the country. This is a sigh of relief and a victory for the Yemeni people, and a strong message from the US that they are putting the interests of Yemenis first,” says Mohamed Abdi, NRC’s country director in Yemen.

Find out more: Risk alert and humanitarian impact in Yemen (ACAPS report)

#6

Aid workers are being

deliberately targeted

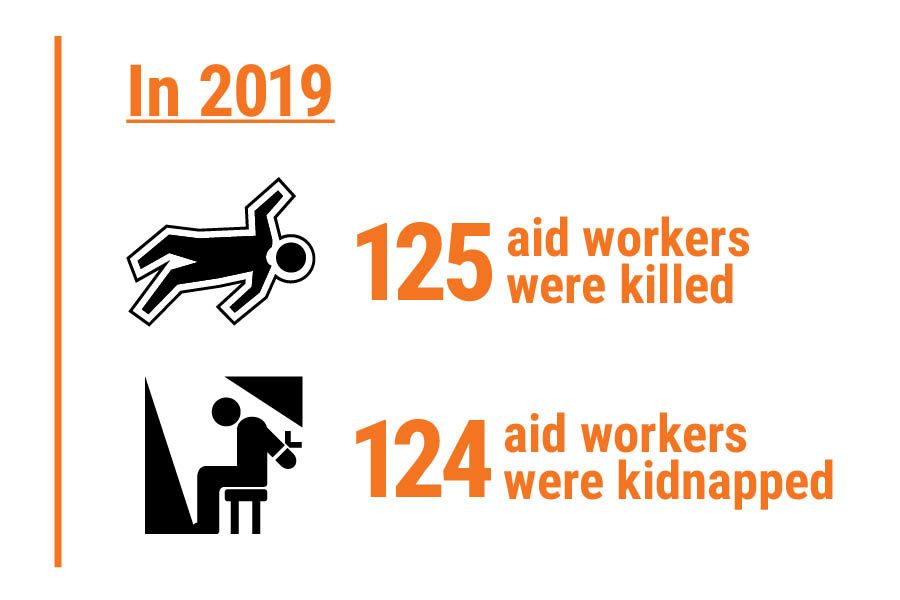

Unprecedented numbers of attacks against aid workers are making it harder to deliver aid to those in need.

Providing humanitarian assistance amid conflict has always been a dangerous and difficult endeavour. However, over the last decade, aid worker casualties have tripled, reaching over 100 deaths per year.

In 2019, 125 aid workers were killed and 124 were kidnapped, according to the Aid Worker Security Database. Aid workers are no longer casual victims but are increasingly being treated as targets.

The most dangerous places to be an aid worker

Syria was, for the first time, the country with the highest number of major attacks on aid workers in 2019 – followed by South Sudan, the Democratic Republic of the Congo, Afghanistan and the Central African Republic.

#7

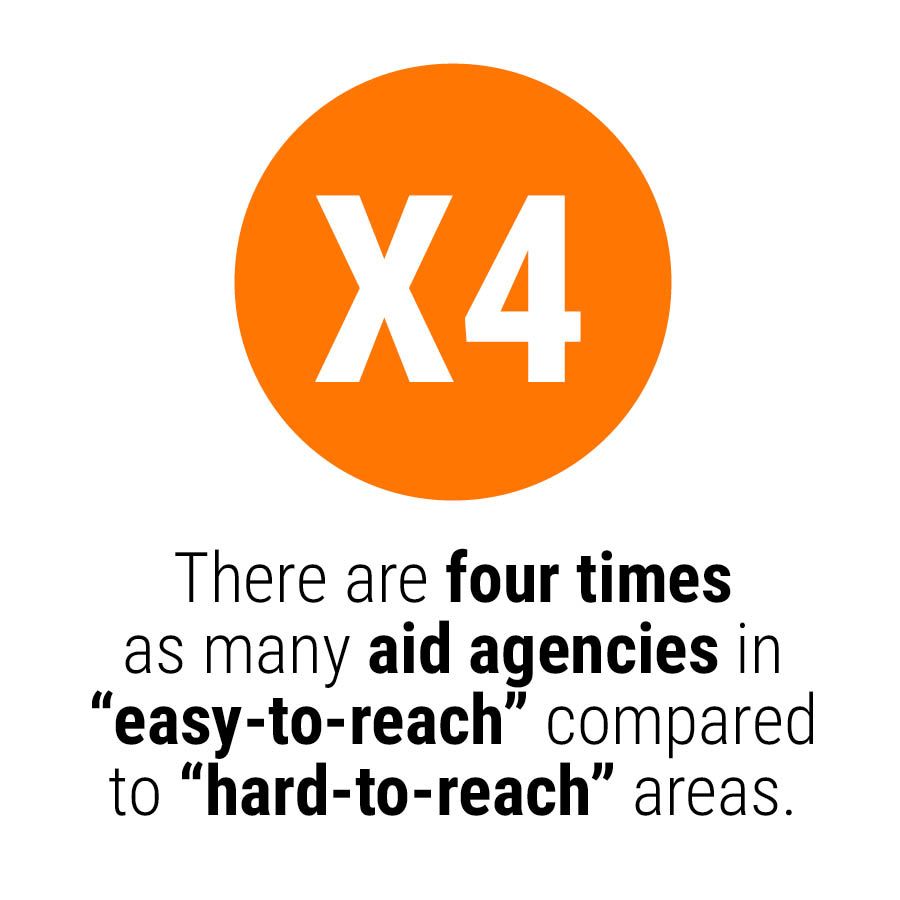

Aid agencies focus

on the easy-to-reach

A high-risk operating environment means some difficult decisions. Aid agencies must balance the needs of people they are trying to serve against the need to avoid harm to those people – as well as to their own personnel, resources and reputation.

“There has been a tendency to focus on the easiest-to-reach populations,” explains Kilani. “In acute emergencies, when assistance is most needed, international staff have been evacuated or go into hibernation, and programmes have been downgraded to skeleton staff or suspended altogether.”

For over 10 years, NRC has been adapting its approaches and ways of working to ensure that this is not the case for our own programmes. A recent survey showed that 50 per cent of the areas where we currently operate are considered “hard to reach” – and we are working hard to increase this figure.

In recent years there has also been a tendency for organisations to “bunkerise” in the face of new threats – cloistering offices in walled compounds, and using armoured cars and armed guards.

“This is a trend NRC and other aid agencies are working hard to change,” says Kilani.

She cites the example of Nigeria: “Developing negotiation strategies and building relationships with other actors … has allowed NRC to overcome some of the constraints faced by other organisations in the country.”

#8

Covid-19 restrictions

are affecting aid

Covid-19 restrictions to reduce the movement of people are having an unintended consequence.

As well as preventing the spread of the virus, they also prevent lifesaving aid from reaching people who have been forced to flee. Hard-to-reach areas are particularly affected.

“If aid workers aren’t allowed to scale up urgent services … because of lockdowns or stay-at-home orders, vital supplies will run out and displaced people will have their lifelines cut off,” says Kilani.

Refugees and internally displaced people are among the most vulnerable people in the world and were already facing multiple crises before Covid-19. The pandemic and governments’ responses to it have tipped many people into a downward spiral that will be difficult to reverse.

Additionally, some assertive governments and armed groups have used the pandemic as an opportunity to extend their control and seek to gain legitimacy. This affects displaced people’s access to services and the ability of aid organisations to reach them.

#9

From hard-to reach

to how-to-reach

NRC has significantly improved its capacity to operate in hard-to-reach areas over the past ten years. As one of the biggest displacement organisations worldwide, working in more than 30 countries, we are committed to taking a lead.

Sarah Kilani has been working with key staff across the organisation to set out a plan for how to make this possible.

“We are already working in 27 of the 35 countries with the most challenging contexts regarding humanitarian access. But there are still a number of areas where NRC can challenge itself to be more relevant,” she explains.

The driving focus of our efforts in these areas is to ensure displaced people have better access to assistance and protection.

“To achieve this, we must change our mindset from ‘when to leave’ to ‘how to stay’. We have to move away from a bunkerised approach towards adopting more nimble, innovative ways to stay and provide assistance despite the odds.”