Stressed

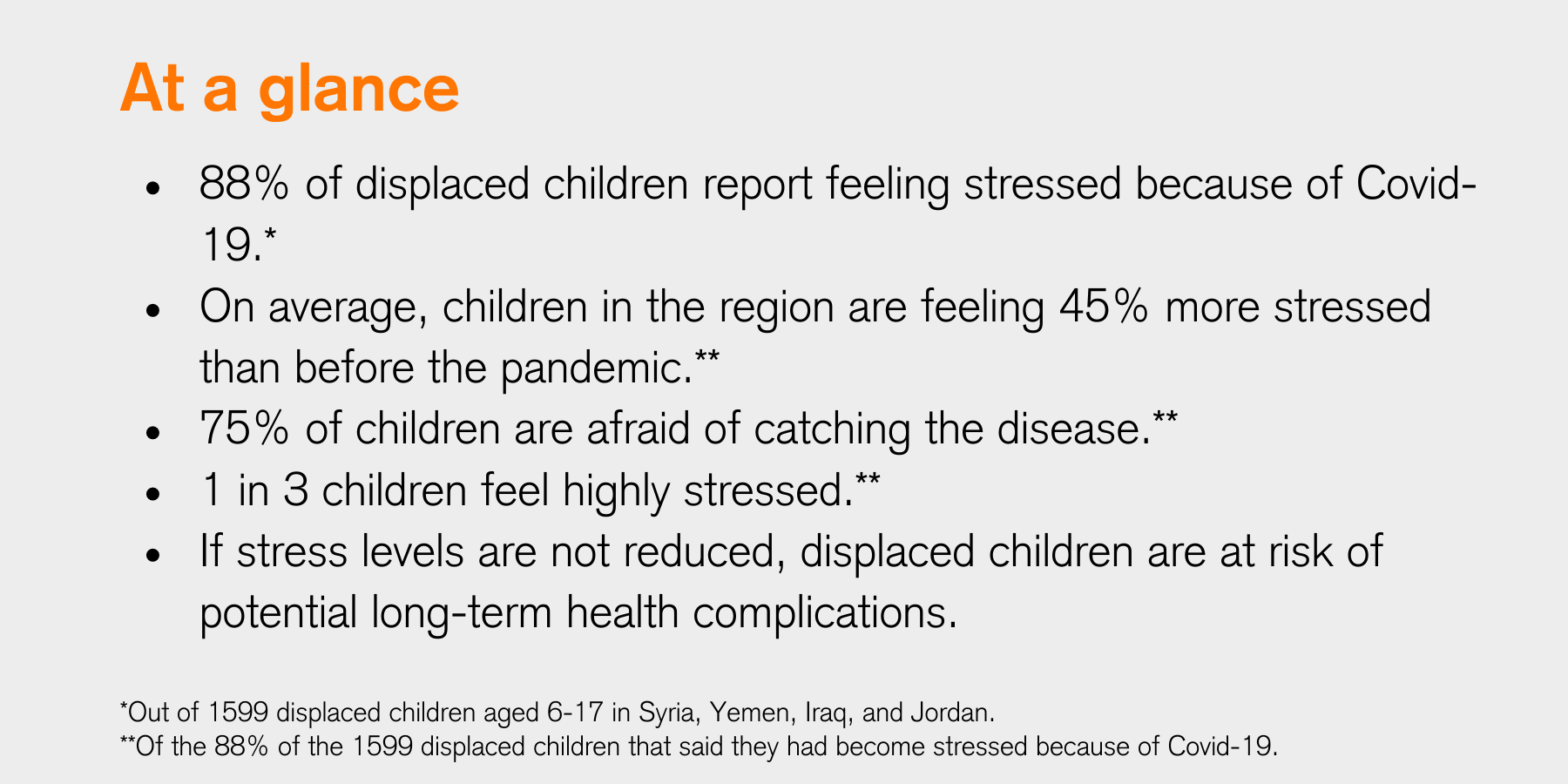

Special report: An NRC investigation finds that the fear of Covid-19 is leading to an alarming rise in stress levels amongst refugee and displaced children in the Middle East.

In late June, we at the Norwegian Refugee Council set out on an eight-week investigation to assess the psychological impact of Covid-19 on refugee and displaced children in the Middle East.

Through a regional survey, qualitative research, expert testimony, and on-the-ground reporting, we have unearthed that children who were once forced to flee hunger, bombs, and bullets, now face an epidemic of fear caused by the global coronavirus. With no end to the outbreak in sight, toxic stress poses a major health threat to the Middle East’s most vulnerable children.

Stress on the rise

Click on the circles below to discover the average increase in stress levels for each country.

How does stress affect children?

Stress is not always a bad thing. Acute stress can enhance our physical and mental performance in times of need. But when it’s continuous, stress can wreak havoc on the brain.

Repeated and prolonged exposure to high levels of stress can be particularly detrimental to children. Evidence suggests that sustained high levels of stress, also known as chronic or toxic stress, can disrupt the development of major organs and lead to stress-related diseases and cognitive impairment. Some studies even indicate that chronic stress can lead to epigenetic changes in our DNA and affect the genes of future generations.

Exacerbated by previous trauma, displaced children are particularly susceptible to experiencing high levels of stress when encountering a new crisis.

A nine-year-old Syrian boy stares out of the door during lockdown in Azraq Refugee Camp, Jordan. Photo: Daniel Wheeler/NRC

A nine-year-old Syrian boy stares out of the door during lockdown in Azraq Refugee Camp, Jordan. Photo: Daniel Wheeler/NRC

Professor Jon-Håkon Schultz from the Arctic University of Norway, one of NRC’s research partners, is an educational psychologist and an expert in crisis and trauma psychology relating to children.

"Research shows that children who have previously experienced traumatic events are more vulnerable to new stress. The new Covid situation can resemble the previous traumatic experiences. It's the feelings of threat to life, possible severe health issues and death and destruction. And these feelings are the same as they experienced during bombings; during the escape; during the war days. It’s not necessarily Covid per se - it’s what Covid brings up in them. It’s a bad situation made even worse."

"When we first heard of corona we were really scared," says 16-year-old Heba from Za'atari Refugee Camp in Jordan. Photo: Daniel Wheeler/NRC

"When we first heard of corona we were really scared," says 16-year-old Heba from Za'atari Refugee Camp in Jordan. Photo: Daniel Wheeler/NRC

Why are children stressed during Covid-19?

How misinformation is leading to fear

Like with a jigsaw, children who only receive snippets of information will try to fill in the blanks themselves using their imagination – often leading to grave misconceptions.

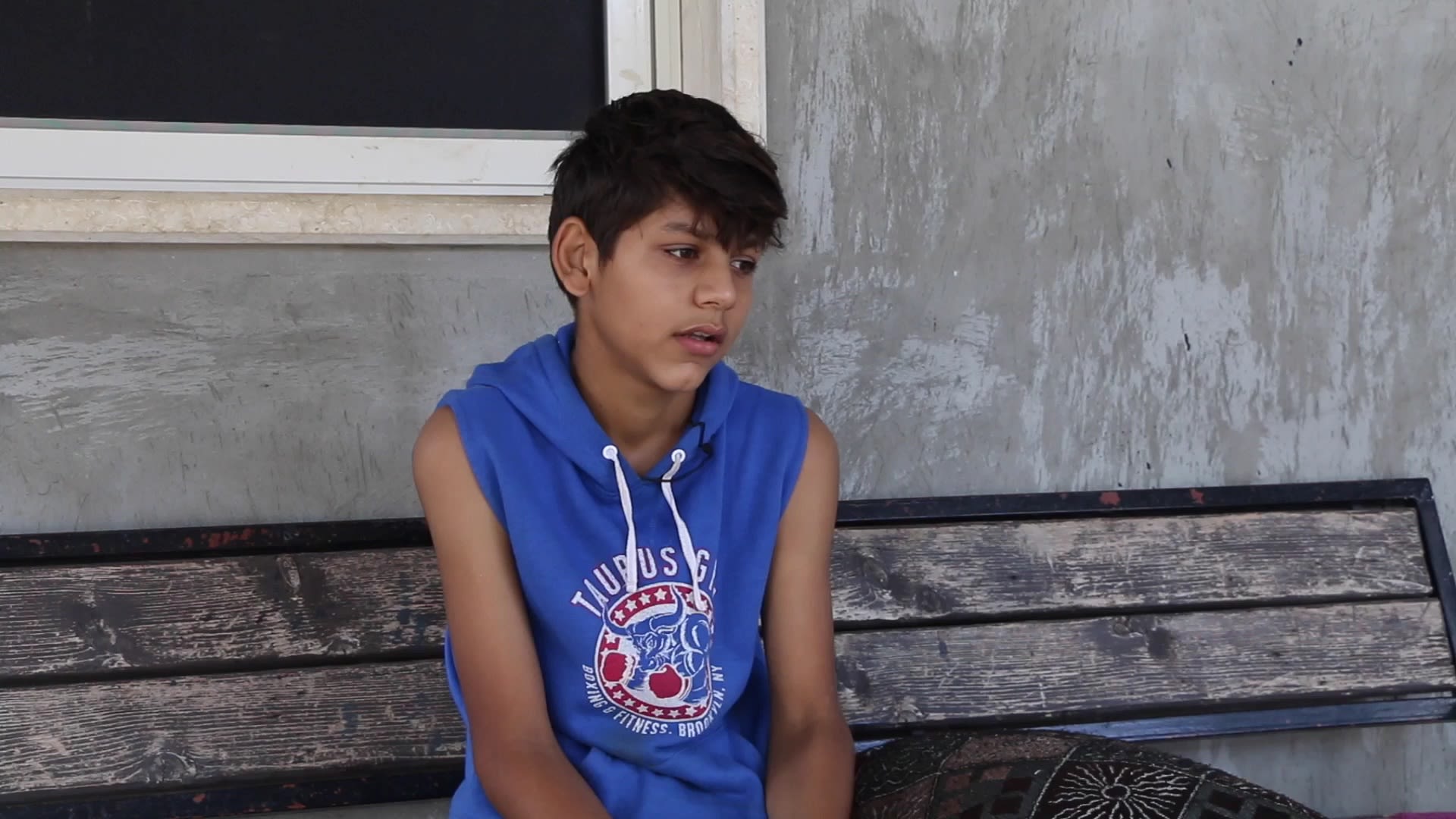

“I feel stressed all the time and it makes my head hurt. We are trapped in a prison with the virus,” says 12-year-old Shaher. When asked what he believes will happen if he becomes infected, Shaher replies: “Maybe life. Maybe death.”

Seemingly unaware that coronavirus is thought to pose very little threat to the physical health of children his age, for Shaher and many other Syrian refugees living in Jordan, fear has become worse than the virus.

Whilst Shaher’s fear is arguably misplaced, it is not completely unfounded. His father, Ashraf, has been unable to work since entry to and from the camp was suspended in early March - a public health measure designed to protect the vulnerable camp population who live in close proximity to one another.

Amongst growing concerns of falling deeper into poverty, Ashraf is worried that his sons are falling even further behind in their education. While Jordan moved quickly to expand online learning to compensate for school closures, not all students have been able to benefit fully, whether due to issues related to accessibility or challenges in following online lessons. "The online classes are not enough,” he says. “The lessons are not interactive, and my sons can’t ask questions if they don’t understand.”

The fear of a missed future

Trapped in the midst of Yemen's brutal war that’s lasted more than five years, 12-year-old Walid lives in a camp for internally displaced people in the south of the country. Although terrified of the virus, Walid is keen to go back to school to pursue his dream of becoming a doctor.

“We are scared of coronavirus, but we want schools to reopen. If the coronavirus continues, our life will be worse. We won’t go to school or play with friends and we can’t do anything,” says Walid.

Walid sits outside his tented home with his schoolbag despite the camp's school being closed. Photo: Mahmoud Al-Filstini/NRC

Walid sits outside his tented home with his schoolbag despite the camp's school being closed. Photo: Mahmoud Al-Filstini/NRC

As the virus establishes a firm foothold across the region, Syrians who once sought refuge in Lebanon now face similar concerns.

"I was happy at school," says Ibrahim. "Now it's so difficult to study or learn. I don't do anything. I sit alone and talk to no one."

Ibrahim's older brother, Mostafa, says his younger sibling's mental health has deteriorated rapidly since schools closed in Lebanon. Photo: Zaynab Mayladan/NRC

Ibrahim's older brother, Mostafa, says his younger sibling's mental health has deteriorated rapidly since schools closed in Lebanon. Photo: Zaynab Mayladan/NRC

Ibrahim was just eight when he fled to Lebanon with his family five years ago. Looking to escape Syria's near decade-long civil war, the family now face even more uncertainty as Lebanon sits on the brink of its own economic and political collapse.

"We watch the situation on the TV. How people are blocking streets and burning tyres," says Ibrahim's 18-year-old brother. "If we are seeing all of these things, how are we supposed to be ok?"

Learn about NRC's response to the recent explosion in Beirut, Lebanon.

A separate NRC wellbeing survey carried out in April showed that almost half (44%) of children interpreted the danger from Covid-19 to be high.

"Everyone is talking about it. Every day there are cases of people dying so we feel afraid."

How are children spending their time?

Hover over the segments to discover the types of activities children have been doing during the pandemic.

During the pandemic, many children are having to look after younger siblings - forcing minors to assume adult responsibilities and denying them of their childhood.

With so many displaced families living in one-room homes, some children are being stressed to breaking point.

"When I get stressed I just stay silent and numb. It’s hard because all of us are at home all the time. I have two sisters and two brothers. Often we argue and get mad at each other."

Discover more of Salam's story by clicking on the images below.

Salam, 15, sits on the doorstep of his home - a caravan in a camp for internally displaced people camp in Duhok, Iraq. He and his family have lived in the camp for over four years, after fleeing Sinjar when it was captured by IS group. Photo: Alan Ayoubi /NRC

Salam, 15, sits on the doorstep of his home - a caravan in a camp for internally displaced people camp in Duhok, Iraq. He and his family have lived in the camp for over four years, after fleeing Sinjar when it was captured by IS group. Photo: Alan Ayoubi /NRC

The camp's school shut down following the outbreak of Covid-19 in Iraq. Since then, Salam and his four siblings have been homeschooled for an entire semester. Photo: Alan Ayoubi /NRC

The camp's school shut down following the outbreak of Covid-19 in Iraq. Since then, Salam and his four siblings have been homeschooled for an entire semester. Photo: Alan Ayoubi /NRC

"Their behaviour has changed a lot. There is a lot of tension between them as they are usually at home. They no longer see their friends like before," says Salam's mother, Fatee. Photo: Alan Ayoubi /NRC

"Their behaviour has changed a lot. There is a lot of tension between them as they are usually at home. They no longer see their friends like before," says Salam's mother, Fatee. Photo: Alan Ayoubi /NRC

"I read or do school work for about four to five hours a day, but the slow internet service has been a challenge," says Salam. Photo: Alan Ayoubi /NRC

"I read or do school work for about four to five hours a day, but the slow internet service has been a challenge," says Salam. Photo: Alan Ayoubi /NRC

In an NRC survey conducted at the start of the pandemic, 735 households in Gaza and the West Bank were asked how their children were coping with distance education. Almost half (48 per cent) reported that their children were feeling increasingly stressed by both the pandemic itself and the fear of falling behind in their classes.

"Children are experiencing sleep disturbances, increased anxiety and even violence. We are not able to reach all of the children who need support because we can’t get to them."

The importance of getting children back to school

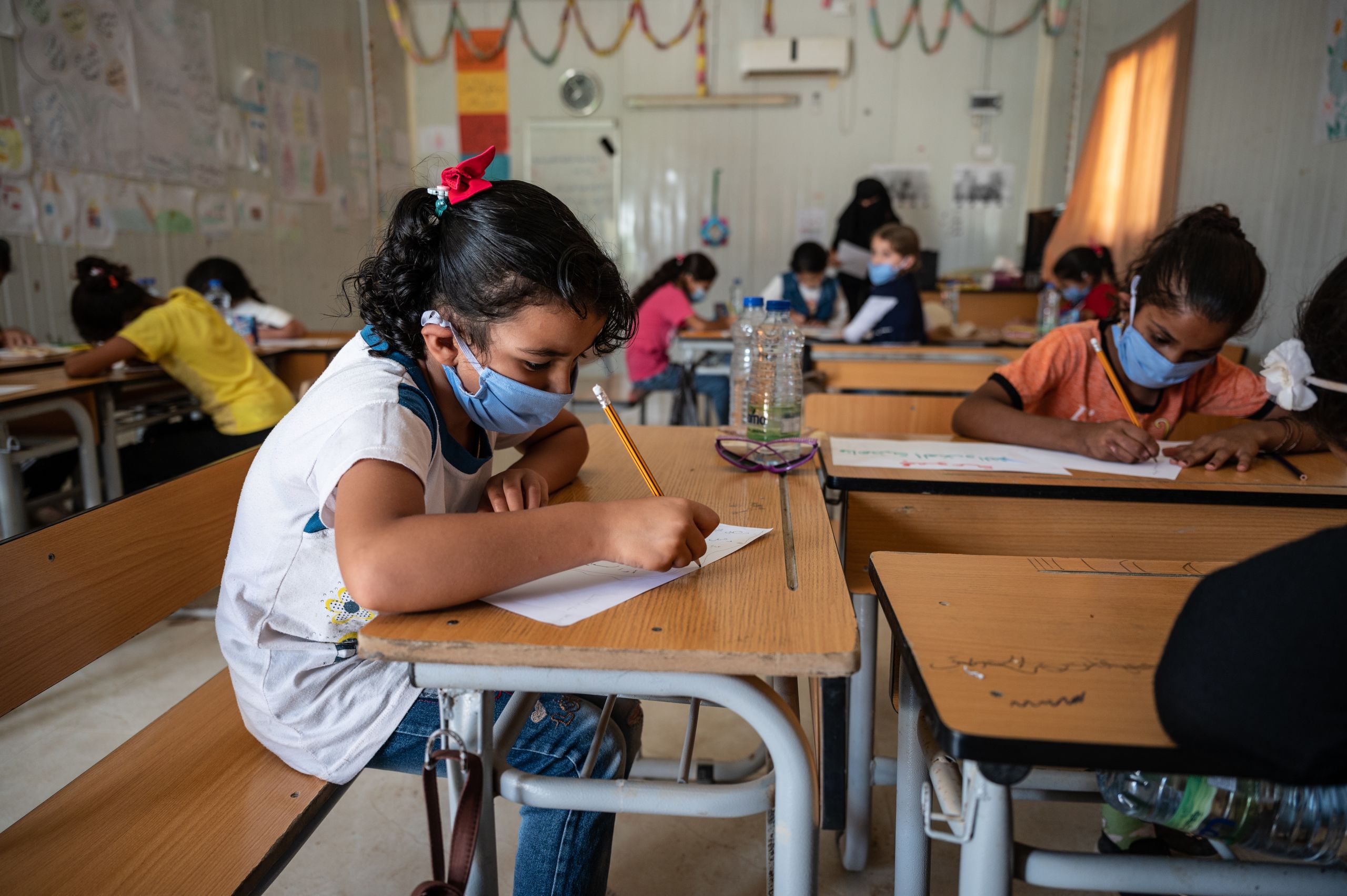

The children of those forced to flee are often at increased risk of not attending school. But getting children back into the classroom is only half the battle.

The hippocampus is one of the regions of the brain strongly associated with learning. In numerous human and animal studies, chronic stress is thought to alter the structure of the hippocampus and ultimately, reduce its volume, shrinking the part of the brain which helps us process emotions, recall memories and learn new things.

That is to say, learning is inextricably linked to emotional wellbeing and without adequate psychosocial support, refugee and displaced children are at risk of falling even further behind in their already fragmented education.

“A very effective way of helping children overcome the negative effects of stress is by having them come back to school. The school environment itself is full of protective factors. In addition, we need to specifically help those students that have had their learning functions impaired. They need extra educational support.”

A young Syrian girl practises her writing at NRC's Learning Centre in Za'atari Refugee Camp. NRC's Photo: Daniel Wheeler/NRC

A young Syrian girl practises her writing at NRC's Learning Centre in Za'atari Refugee Camp. NRC's Photo: Daniel Wheeler/NRC

A right to wellbeing

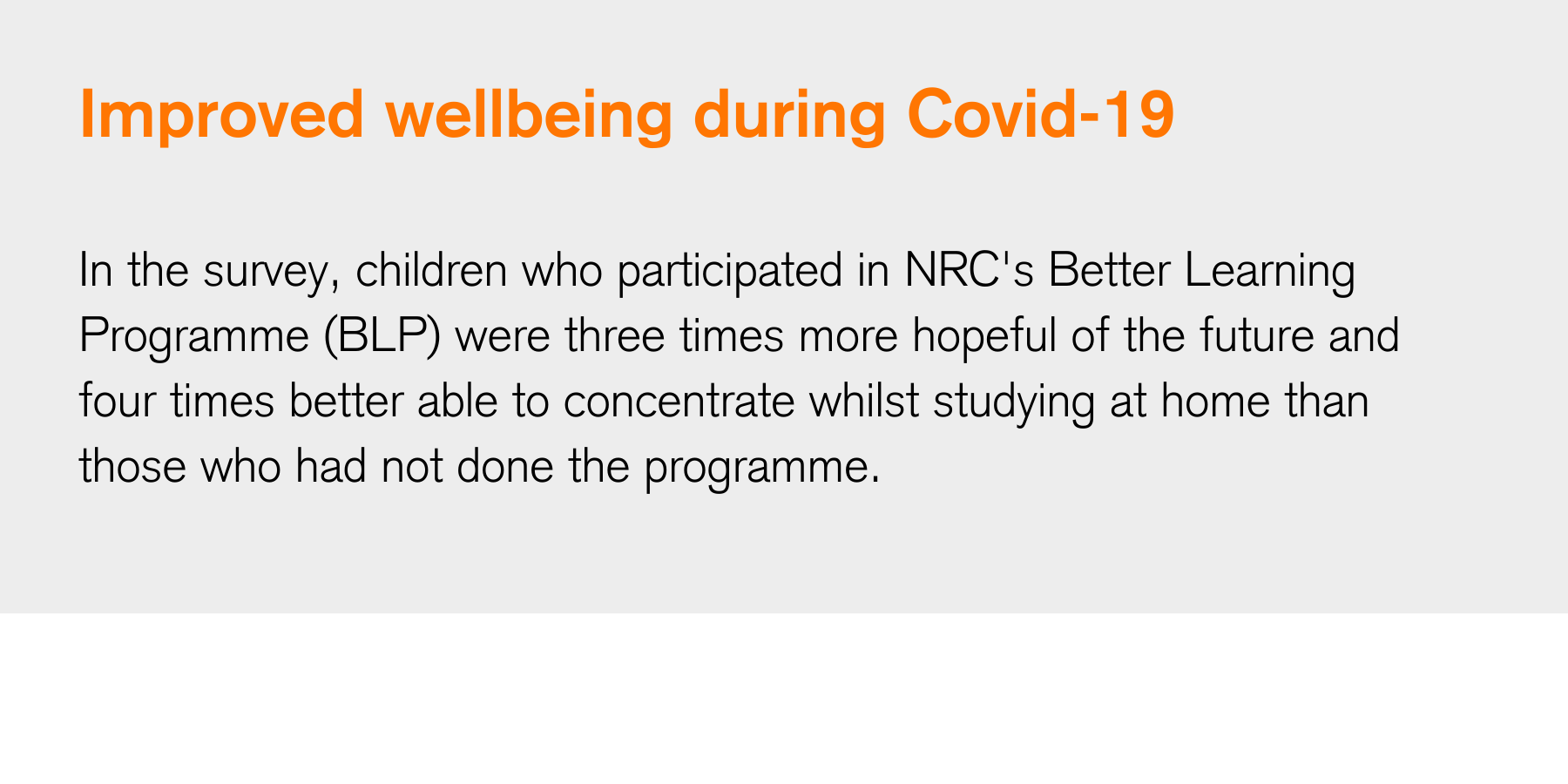

Since 2012, NRC and the Arctic University of Norway have been working with conflict-affected communities as part of NRC’s flagship psychosocial support intervention, the Better Learning Programme.

“Since its inception in Palestine, the Better Learning Programme has helped to improve children’s wellbeing in the most severely conflict-affected communities. Through our collaboration with research partners, we have been able to continuously increase the quality and the relevance of the programme – leading to children having an improved sense of wellbeing and better conditions to learn in the classroom.”

Recognised by a number of international conventions, the right to education is considered a fundamental human right. Now it’s time to ensure that children not only have a right to education but also have a right to wellbeing.

Our recommendations to:

Governments, intergovernmental and nongovernmental actors

- Mental health and psychosocial support services must be made widely available to children and their families in conflict-affected communities during and after displacement in order to respond to the stress caused by the pandemic.

- Longer-term funding for mental health and psychosocial support service programmes is needed to support research as well as longer-term capacity development plans. These two areas contribute to improving the quality of service delivery and developing more sustainable interventions.

- Despite it being important to relay the seriousness of the pandemic and the need to subscribe to the necessary precautions, children should be made aware of the reality of the threat that the virus poses to them, in order to avoid unnecessary suffering. Efforts should be made to combat misinformation and misconceptions about Covid-19 within refugee and displaced communities and ensure that children are communicated with directly.

Members of the public

- Displaced children need your help. The impact of coronavirus will be devastating and far-reaching if we do not reach those who need us.

Suggested reference for this publication:

Norwegian Refugee Council (2020). Stressed: A special report on the psychological impact of Covid-19 on refugee and displaced children in the Middle East. Norwegian Refugee Council: NRC, Ammanhttps://www.nrc.no/shorthand/stories/stressed/index.html