Mohamed ate grass to survive

Syria has entered its tenth year of conflict. More than 400,000 people have been killed since 2011, according to the UN. One who nearly lost his life was Mohamed. When his neighbourhood was besieged in 2013, no supplies could get in. For a year and a half, he starved in Yarmouk – a neighbourhood of despair.

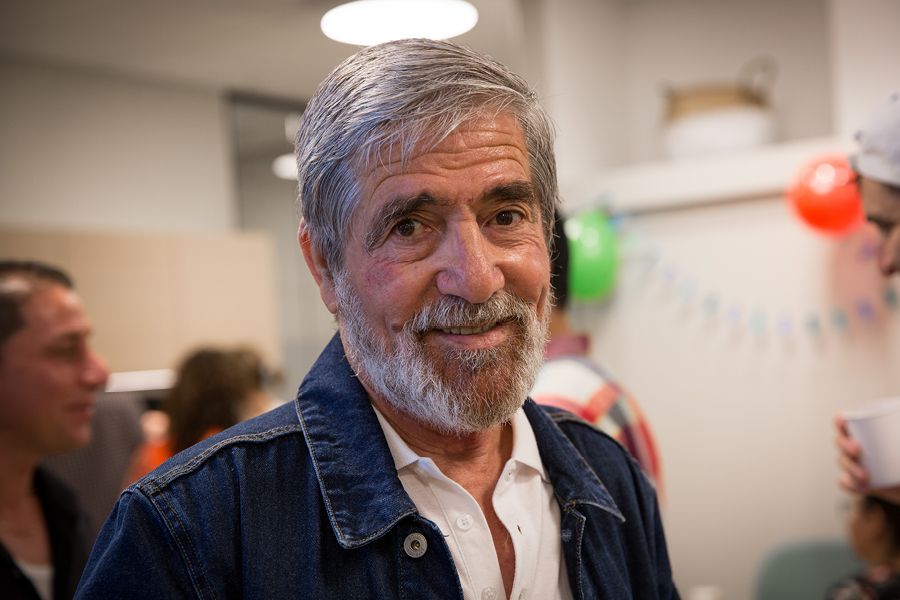

Life is so much better now. He has been through several surgeries and got his teeth fixed. For the first time in his life, Syrian Palestinian Mohamed has received a passport – a Norwegian passport. Photo: Ingebjørg Kårstad/NRC

Life is so much better now. He has been through several surgeries and got his teeth fixed. For the first time in his life, Syrian Palestinian Mohamed has received a passport – a Norwegian passport. Photo: Ingebjørg Kårstad/NRC

Tøyen is a multicultural district of Oslo, home to people from Asia, Africa, America, Eastern Europe and Norway. In the centre of Tøyen is a lively square called Tøyen Torg, lined with cafés, shops and a library.

Every day, Syrian Palestinian Mohamed, 61, fills his jacket pockets with his homemade roasted almonds. He puts on his sunglasses, picks up his cane and walks out of his flat in Tøyen. As he makes his way to Tøyen Torg, he greets his neighbours with a smile and gives them a handful of nuts.

He crosses the square and enters the Centre for Refugee Competence and Integration (SeFI). The people who work there are his friends and family. They have helped him recover through heart surgery, shoulder surgery, eye treatment and rehabilitation. They have helped him get his teeth fixed. They have helped him feel at home in Tøyen.

Mohamed plays cards and talks to the staff and other locals. Afterwards, he returns home to his wife, children and cat.

But the traumas come back to him in the night. In his sleep, he relives the siege of Yarmouk. He dreams that someone is choking him.

Then he wakes up, fearing for his life.

Siege in war

One of the objects of a siege is to cut the enemy’s supply lines; it has been used as a tactic in warfare for centuries. There were sieges during both World Wars. They were used in Vietnam and in Sarajevo, Bosnia and Herzegovina. And more recently, by warring parties in Iraq, Yemen and Syria.

“Essentially, siege as such is not prohibited in warfare. But it is hard to do it lawfully in today’s conflicts where fighting takes place in populated areas,” says Tobias Köhler, 37, of the Norwegian Refugee Council (NRC). He is an expert on international humanitarian law – the rules of conduct for armed conflict. Köhler says that international humanitarian law as defined in the Geneva Conventions and other treaties is designed to ensure that all those not or no longer fighting– in other words, civilians, the wounded and prisoners of war – are treated in a humane manner and not targeted.

NRC’s Tobias Köhler is an expert on international humanitarian law. Photo: Ingebjørg Kårstad/NRC

NRC’s Tobias Köhler is an expert on international humanitarian law. Photo: Ingebjørg Kårstad/NRC

“The rules say that you are not allowed to take from the civilian population what they need to survive. And that you actually have a duty to make sure civilians get what they need. This applies to both sides – both those carrying out the siege and those who have been besieged. They must agree to allow relief,” he explains.

Still, both parties sometimes refuse to allow access to aid – even though it can be a war crime. Then the parties often use arguments against each other that end up affecting the civilian population:

“Those who are under siege might say: ‘You are starving our children, you must stop this.’ And those who are carrying out the siege might say: ‘You give the aid you receive to your fighting forces and we can't allow that’,” continues Köhler.

For NRC and the other aid organisations, the principles of humanity, impartiality, independence and neutrality are essential for us to be able to carry out our humanitarian work. When the population does not get what they need to survive, it is crucial for aid organisations to gain access:

“If the parties have broken the rules, one way to get out of this problem is to allow aid organisations to help the civilian population. To achieve this, we put forward strong arguments to both parties, as to what their obligations actually are: which is to adequately supply the civilian population or otherwise accept the help we can offer. We explain that there is sense behind the law, that it strikes a balance between military necessities and basic humanitarian principles. For example: relief is supposed to reach civilians, not fighting forces, and organizations are doing their best to ensure this. And that without these rules we are left with barbarism,” Köhler concludes.

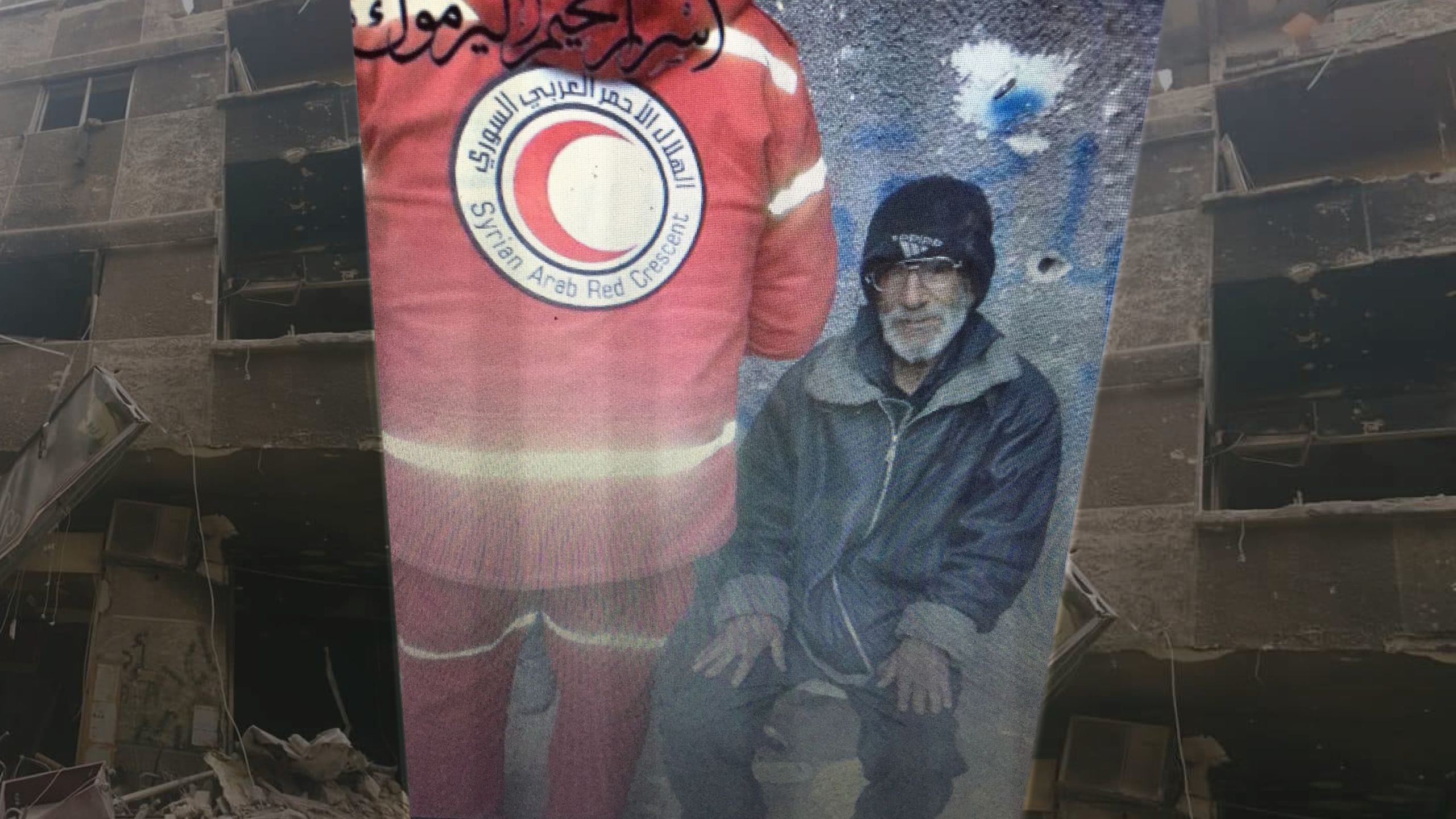

This photo is from the Harasta neighbourhood in Eastern Ghouta, where 400,000 people were besieged during the Syrian war. Today, large parts of the country are in ruins and tens of thousands of Syrians have no home to return to. But some have returned and are trying to rebuild their homes. Photo: Karl Schembri/NRC

Life before the war

Yarmouk is located outside of the capital of Damascus. It started as a Palestinian refugee camp, but quickly developed into a large and well-functioning city district. Before the war broke out in 2011, around 160,000 Palestinian refugees and more than half a million Syrians lived in Yarmouk.

“In 1948, my parents were forced to flee Palestine. They went to Syria, and I was born in Damascus. I have six siblings.

“In Damascus, my father first started working as a roadworker, and later he became a driver,” Mohamed says.

Mohamed talks about his life. Something he will never forget was when he woke up to a man standing over him pointing a firearm at his forehead. The event comes back in the dreams at night. Photo: Ingebjørg Kårstad/NRC

Mohamed talks about his life. Something he will never forget was when he woke up to a man standing over him pointing a firearm at his forehead. The event comes back in the dreams at night. Photo: Ingebjørg Kårstad/NRC

It is summer 2019 and we are sitting in the living room in his flat in Tøyen. The table is set with coffee cups and a plate of biscuits. Syrian music is playing on the TV. Mohamed and his wife have seven children between the ages of 14 and 35. The three youngest live at home. One of their daughters lives in Syria. Their eldest son fled Syria to Thailand and from there to New Zealand.

“When my parents fled, they had to leave everything they had built up throughout their lives. They had to start all over again in a place that was lacking in most things.

“As children, we didn’t get what we needed or wanted. We couldn’t afford to buy anything. The conditions were terrible. There was no proper sewage system, and we lived in run-down houses. We didn’t have electricity. We had to read by the light of a gas lamp. But we went to school – Palestinians are very concerned about their children getting an education, whatever the cost,” says Mohamed, who completed high school.

As a young man in Syria, Mohamed built his own house. Photo: Private

As a young man in Syria, Mohamed built his own house. Photo: Private

“Then, like most others my age, I wanted to start working so I could start a family. I learnt how to build concrete houses. I bought tools, started my own business and built my own house. After a while, I had ten employees, and later I had 20. Life was good. I was only 23 years old, but I owned a four-bedroom house with a living room, a bathroom and a kitchen. I was married and had two children.

“Then, new building regulations were passed. People were no longer allowed to build and the market dried up. So I went to Libya. Life was hard there. I was still working in the construction industry, and I had brought my own equipment. I had people working for me. But when the Libyans were supposed to pay us, they would say: ‘No, you’ve had enough.’

This picture was taken in Libya, where Mohamed stayed for several years. This was not a happy time. Photo: Private

This picture was taken in Libya, where Mohamed stayed for several years. This was not a happy time. Photo: Private

“I was there for a long time, but not of my own accord. Libya was under blockade and, as a Palestinian, I couldn’t travel anywhere. I lost 17 years of my life.

“Finally, I was able to return to Syria. In Yarmouk, I had to start from scratch again. But things went fast, very fast. I bought tools and equipment, and I bought a car. I built my business back up again.

“Then the war came.”

“Hell on earth”

Eastern Ghouta, Idlib, Aleppo. We know all the names from the news. Sieges have been widely used in Syria since 2011. In November 2016, according to the UN, there were nearly one million civilians suffering under siege.

Yarmouk became a battlefield as early as 2012. The civilian population ended up in the line of fire between the warring parties. The area was destroyed by urban warfare, air strikes and missile attacks.

A photograph of the sea of humanity pushing through the ruins of the destroyed neighbourhood made an impression on the whole world. The picture was taken in the third year of the war. Thousands of people in Yarmouk were desperate for their rations of very delayed, and far too scarce, emergency aid. This photograph led to Yarmouk becoming known as “hell on earth.”

One of those who lived there at the time was Mohamed.

NRC is one of the few aid organisations operating throughout the whole of Syria helping hundreds of thousands each year across conflict lines. We cover the needs of as many as possible who have been affected by the conflict. We also help Syrian refugees in neighbouring countries, including Iraq, Lebanon and Jordan. Read more about our work in Syria here.

NRC is one of the few aid organisations operating throughout the whole of Syria helping hundreds of thousands each year across conflict lines. We cover the needs of as many as possible who have been affected by the conflict. We also help Syrian refugees in neighbouring countries, including Iraq, Lebanon and Jordan. Read more about our work in Syria here.

Hunger

Yarmouk was besieged by various groups including forces aligned with the government, the opposition and the Islamic State (IS) group.

“They were shooting at each other. I was told that a little boy got shot when he was collecting leaves to eat”.

“Armed men entered our neighbourhood, committing vandalism, robbing shops and stealing cars. I sent my wife and children out of Yarmouk to a home we rented. I stayed behind to look after our house.

This clip is of Eastern Ghouta, outside Damascus. It shows how devastating the situation is after all the bombings. Photo: NRC

This clip is of Eastern Ghouta, outside Damascus. It shows how devastating the situation is after all the bombings. Photo: NRC

“There was no electricity. For the first few months, food was still getting into Yarmouk. But eventually it stopped. People had to be careful with the food they still had at home. I had hidden away some rice and sugar.

“I lived in our house along with my friend. One night I woke to a strange man pointing a rifle at my head. They blindfolded us and tied us together. They stole all the food I had. When they left, we tried to get loose. My friend managed to and then he helped me.

“There is an edible plant with green leaves. We call it khubese [a green similar to spinach]. I don’t think it exists in Norway. Some people risked their lives by going to the outer limit of the siege area to pick this plant, which they then sold to us. They could have been shot.

“Other times, we ate cactus leaves. We cleaned the leaves, divided them into pieces and dipped them in bouillon.

“For a period, there was no food at all. We heard that someone was handing out soup so we went to see. It was watered down bouillon. We got one and a half cups each. My body could no longer tolerate the salt in the broth, and I woke up the next day with such swollen feet that I couldn’t put on my shoes.

“After 550 days, 128 people had starved to death. Today, I look like a human. But I’ll show you a picture that was taken right after I left the camp. You won’t recognise me. I dropped from 75 to 40 kilos. I lost so much muscle mass that I could barely stand.”

Food

May 2015. All Mohamed could think about was getting out of Yarmouk. He tried to think of anyone he knew who might be able to help him.

In the end, he just could not go on. He called his wife and sister and said: “I can't go on. I have to get out or I’ll die.”

“My sister’s husband knew people. They managed to get me out by bribing someone. I thought: the first thing I’ll do when I get out is eat. Bread and harissa [a chilli paste containing smoked red pepper],” says Mohamed and laughs:

“We came to some friends. They made so much food that it filled the table! I didn’t know where to start. I was voracious. I just ate and ate. I wanted to taste everything. But it wasn’t enough!

“When I got to the home we rented, I told my wife I wanted more food! The first few days, I ate all the time. I’m usually not fond of sweets, but I ate lots of cakes.”

“Father, have some Red Bull”

One of Mohamed’s daughters had lived in Norway for 15 years, and was married to a Norwegian Syrian.

“My daughter called and asked me if I was in good shape. I told her I was, and she said: ‘Then you can come to Norway. You will have to walk most of the way.’

“Naturally, I was scared. We had to walk at night. I was afraid of being stopped and getting caught. Turkey, Greece, Macedonia, Hungary.

The journey through Europe. Mohamed was ill and had trouble walking, but he received help. Photo: Private

The journey through Europe. Mohamed was ill and had trouble walking, but he received help. Photo: Private

“There were 18 of us walking through the forest. I had pain in my legs and hips. I could barely breathe. I had a bad heart. One of the others pulled out an energy drink from his bag and said: ‘Father, have some Red Bull.’ They took turns helping me. I was very tired. Finally, I said: ‘Just go ahead, forget me.’

“But they waited for me.

“We slept in the woods. It was cold, we nearly froze to death. All I had on was a pair of trousers, a shirt and a jacket. We had to cross a river, and the icy water came up to my waist.

“You never knew what might happen. You didn’t know if someone might come and kill us.

“In Austria, we managed to get a car and drove to Germany. The trip from Germany to Norway went smoothly.

“We drove straight to Oslo.”

In Oslo

Mohamed says there were some months at the asylum reception centre when he was not well. He struggled with health problems. Later, he moved and underwent several operations. He received help and found friends at SeFI. After a year and a half, his wife and children came from Syria to Norway to join him.

“I like living in Tøyen. I am grateful for all the help I have received”, says Mohamed.

He looks worried. He then adds:

“But we have been told that the municipality plans to shut down SeFI. That makes me very sad. I don’t want to lose my friends. They are the only ones I have.

“It feels like I’m being displaced again.

Sources: UNWRA, the Great Norwegian Encyclopedia, Marte Heian-Engdal at Dagsavisen, Wikipedia, NTB, Aftenposten.