“Home” is where the hope is

If you are a refugee, you have probably escaped a terrible situation – such as conflict, war and violence. It has affected you deeply and may have ruined you, your family and those around you.

“Maybe you arrive at a refugee camp. There you can find protection and get back on your feet,” says Jon-Håkon Schultz, professor of educational psychology at the University of Tromsø, in northern Norway.

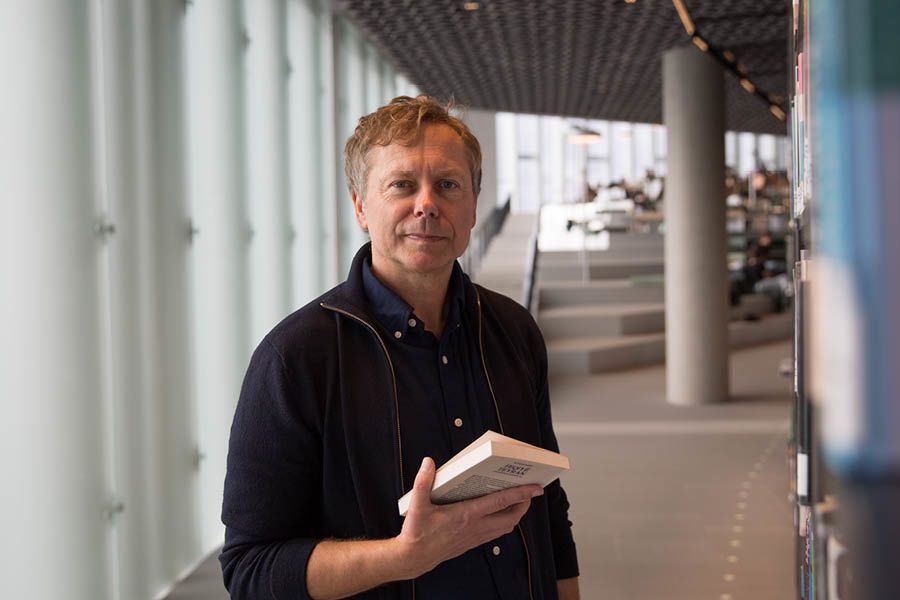

Professor Jon-Håkon Schultz and University of Tromsø have collaborated with the Norwegian Refugee Council for a number of years. Photo: Ingebjørg Kårstad/NRC

Professor Jon-Håkon Schultz and University of Tromsø have collaborated with the Norwegian Refugee Council for a number of years. Photo: Ingebjørg Kårstad/NRC

For years, he has been travelling between Tromsø and refugee camps in countries such as Palestine, Jordan, Lebanon and Iraq. Jon-Håkon Schultz has led the work of developing the Norwegian Refugee Council’s “Better Learning Programme”, which helps children deal with trauma and stress.

When big sister Malak notices that her little siblings are bothered by stress, she gets them to participate in relaxation exercises that she has learned from NRC’s Better Learning Programme. The siblings live in Zaatari camp, Jordan. Photo: Leen Qashu/NRC

“Through the programme, children who struggle with stress and nightmares after traumatic experiences of war and displacement receive help to bring down their high levels of anxiety. This gives them more energy to focus on learning at school,” says Shultz, and continues:

“The children gain routines, security and friends. By giving them structure in their lives, NRC gives them something that helps them survive in their new situation as refugees: hope.”

This also helps the children to feel they have a home away from home.

NRC works to support refugees and displaced people in over 30 countries around the world. Support our work today.

When big sister Malak notices that her little siblings are bothered by stress, she gets them to participate in relaxation exercises that she has learned from NRC’s Better Learning Programme. The siblings live in Zaatari camp, Jordan. Photo: Leen Qashu/NRC

When big sister Malak notices that her little siblings are bothered by stress, she gets them to participate in relaxation exercises that she has learned from NRC’s Better Learning Programme. The siblings live in Zaatari camp, Jordan. Photo: Leen Qashu/NRC

What it’s like to be a refugee

You just had to get away. You couldn’t stay there anymore. You left everything behind. Everything you loved. Your entire livelihood.

Maybe you’ve witnessed people getting killed. Maybe you’ve lost everything you owned. Or maybe you’ve been hungry. Experienced physical abuse. Known extreme fear. Been sexually abused, imprisoned or tortured.

The journey itself may have lasted for days, weeks, months or years. Your family may have been forced to split up. You may have been robbed, mistreated, exploited and forced to commit criminal acts. You may have seen torture and killings. You may have had to watch family and friends die.

Time helps

“Normally, when you are exposed to something very frightening, and a possibly traumatic event, you experience strong reactions,” says Schultz.

But people are adaptable.

“For most people, these reactions will go away on their own over time, and 70 to 80 per cent of people who experience isolated traumatic events will not experience permanent difficulties. It tends to be those who experience many traumatic incidents who are more likely to have long-term problems,” Schultz explains.

He smiles:

“So, in most cases, people will be fine. And why is that? It’s because we manage to remove refugees from ongoing situations – out of war and conflict. We help them. Give them a temporary home. Space to breathe.”

NRC works to support refugees and displaced people in over 30 countries around the world. Support our work today.

Space to breathe

It can be incredibly liberating to come to a refugee camp. Finally, you are safe. A refugee camp is intended – and designed – to be a temporary solution.

It’s a place where you can get back on your feet and get help – “as long as everything is working as it should,” says Schultz. He explains that, in his collaboration with NRC, he has been to many refugee camps.

A reception centre for refugees in Kala Meera village, close to the Iraq-Syria border. The photo is from October 2019. Photo: Alan Ayoubi/NRC

So, where do displaced people live?

Everyone needs a place to live. At the beginning of 2020, there were almost 80 million people worldwide who had been displaced by war and conflict. Nearly half of them were children and young people under the age of 18.

A 2018 report from The World Refugee Council showed that 60 per cent of all those who have fled to another country, and 80 per cent of people who are displaced inside their own country, live in urban areas.

The vast majority move to areas near towns or villages, where there are more opportunities to find work. This can put pressure on the local population, who may also need work and assistance.

The solution is to cooperate with the local population. For example, at NRC we buy goods and services from local people, offer their children schooling or perhaps repair their damaged houses in exchange for refugees being allowed to live there for a while. In this way, we support both the refugees and the local community – and avoid conflict. We work for peace.

In refugee camps, there are few job opportunities and people are unable to become financially independent. This also makes the camps expensive to operate. For NRC, the goal is to find better and lasting solutions.

But sometimes you have no choice: there is an acute crisis and people must have somewhere to live right there and then. In times like that, a refugee camp is the solution.

Refugee camps are typically built either by the authorities, the UN refugee agency, or aid organisations such as NRC. Refugee camps are intended to be a response to an acute crisis and are a temporary measure.

But when the conflicts that people fled from are not resolved and become protracted, people cannot return home. The chance of gaining residency in a third country is usually minimal. Consequently, people have no choice but to stay in the camp. Some camps stand for years and grow as big as cities. For example, the Zaatari refugee camp in Jordan was set up as a temporary camp in 2012, but there are still around 80,000 people living there.

A mother holds her daughter at the reception centre in Kala Meera village, northern Iraq. The refugees face an uncertain future. Photo: Alan Ayoubi/NRC

A reception centre for refugees in Kala Meera village, close to the Iraq-Syria border. The photo is from October 2019. Photo: Alan Ayoubi/NRC

A reception centre for refugees in Kala Meera village, close to the Iraq-Syria border. The photo is from October 2019. Photo: Alan Ayoubi/NRC

A mother holds her daughter at the reception centre in Kala Meera village, northern Iraq. The refugees face an uncertain future. Photo: Alan Ayoubi/NRC

A mother holds her daughter at the reception centre in Kala Meera village, northern Iraq. The refugees face an uncertain future. Photo: Alan Ayoubi/NRC

“I talked to people in camps who were grateful to be there,” recalls Schultz. “And it’s not difficult to understand. They were in mortal danger because they were living inside IS group territory, for example. Finding a refugee camp saved their lives.”

“But when I returned six months later and met the same people, I could see that the camp was now starting to work against its purpose. It was starting to become negative. The people wanted to leave. They wanted to live ordinary lives. They wanted to plan for the future,” says Schultz.

For those of us who live in countries without war, it may be difficult to understand what it means to be unable to plan ahead. Not to have any form of predictability regarding what’s going to happen next in your life. What does it really do to people?

“Without hope, there is only hopelessness,” he answers.

When hope is on the outside

Schultz believes that refugees have far more opportunities when they can live in local communities rather than in refugee camps:

“The big difference is that it is more like leading a normal life. In a refugee camp, everything is temporary.

Women in Zaatari camp, Jordan, wait their turn to collect aid items from the UN refugee agency. The items include mattresses, kitchen equipment and cash. Photo: Leen Qashu/NRC

“I have heard that people live in refugee camps for an average of 15 years. That can be directly harmful. Then, it is absolutely crucial that the children have the chance to go to school.”

Kodo and her children stand in the entrance of their makeshift tent in Ngala camp, north-east Nigeria. Photo: Tom Peyre-Costa/NRC

He taps his index finger on the table:

“I say: school, school, school.”

Then he looks up:

“And NRC are major players in this area.”

NRC works to support refugees and displaced people in over 30 countries around the world. Support our work today.

Women in Zaatari camp, Jordan, wait their turn to collect aid items from the UN refugee agency. The items include mattresses, kitchen equipment and cash. Photo: Leen Qashu/NRC

Women in Zaatari camp, Jordan, wait their turn to collect aid items from the UN refugee agency. The items include mattresses, kitchen equipment and cash. Photo: Leen Qashu/NRC

Kodo and her children stand in the entrance of their makeshift tent in Ngala camp, north-east Nigeria. Photo: Tom Peyre-Costa/NRC

Kodo and her children stand in the entrance of their makeshift tent in Ngala camp, north-east Nigeria. Photo: Tom Peyre-Costa/NRC

The nightmares

One day – and hopefully as soon as possible – the children will move out of the refugee camp.

“That’s why it is so important that we – through NRC’s Better Learning Programme – help free them from the stress and traumatic nightmares. So that the children can make use of the time they actually live in the camp. We can help them get into the right frame of mind for learning and learn good routines at school. This lays a good foundation for their future lives,” says Schultz enthusiastically.

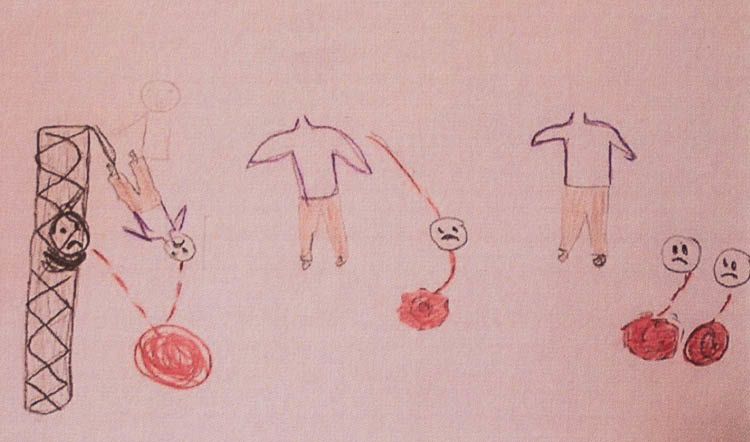

This children’s drawing is from 2018 and shows beheadings. The drawings help the children to talk about their nightmares and what they have experienced. Photo: NRC

This children’s drawing is from 2018 and shows beheadings. The drawings help the children to talk about their nightmares and what they have experienced. Photo: NRC

He explains that the children have not only experienced terrible things during the war, they have also experienced atrocities during their flight. When they finally arrive at a new, safe place, there are a good number of them who struggle with nightmares, fear and lack of sleep.

Activities in between classes at the NRC Learning Centre in Zaatari camp, Jordan. Photo: Thilo Remini/NRC

Many of them have been out of school for a long time. Simply starting school again – although it sounds so easy – can be difficult for many. Even if there is a school, the children must be motivated and helped to return. It must feel safe.

“Here, NRC is doing a great job by

1) making school available,

2) helping children get back to school and

3) helping them learn to relax and make use of their learning,” explains Schultz.

Activities in between classes at the NRC Learning Centre in Zaatari camp, Jordan. Photo: Thilo Remini/NRC

Activities in between classes at the NRC Learning Centre in Zaatari camp, Jordan. Photo: Thilo Remini/NRC

Home

It comes to us early, the feeling that this is where we belong. That this is where we live, and that this is my community. We feel naturally rooted to the place. A feeling of security. As we grow, the world gradually grows larger. But home is still home.

Then, some – as many as 80 million people in the world today – will be forced to flee their homes.

What about homesickness?

“I’ve talked to many displaced children and teachers who say that they think back to their homes. And then it is not recent years they long to return to, but the time before the war. They definitely don’t want to return to their homes as they are now. Now, it’s dangerous.”

Kasaï-Central province in DR Congo was the centre of an armed conflict that displaced 1.6 million people. Today the region is relatively calm and people are returning home – but many find their houses destroyed. Photo: Itunu Kuku/NRC

Schultz smiles:

“That’s why it’s so incredibly liberating – even if you only have a small tent or a shack – that you are able to find safety.

“That you can have a home.”

NRC works to support refugees and displaced people in over 30 countries around the world. Support our work today.

Kasaï-Central province in DR Congo was the centre of an armed conflict that displaced 1.6 million people. Today the region is relatively calm and people are returning home – but many find their houses destroyed. Photo: Itunu Kuku/NRC

Kasaï-Central province in DR Congo was the centre of an armed conflict that displaced 1.6 million people. Today the region is relatively calm and people are returning home – but many find their houses destroyed. Photo: Itunu Kuku/NRC