Helping Palestinians stand up to the forces of displacement

A miracle

For Ali Jabarin, 60, it is “a miracle” that his village still exists. This small hamlet called Jinba, in the southern West Bank, stands as a testimony to the residents’ perseverance.

“When Israel declared our land a military firing zone in the 1980s and completely demolished our village, we rebuilt it the same night,” Jabarin says.

“In 1999, they put us on trucks and forcibly transferred us many kilometres to the north – we came back the very same day.”

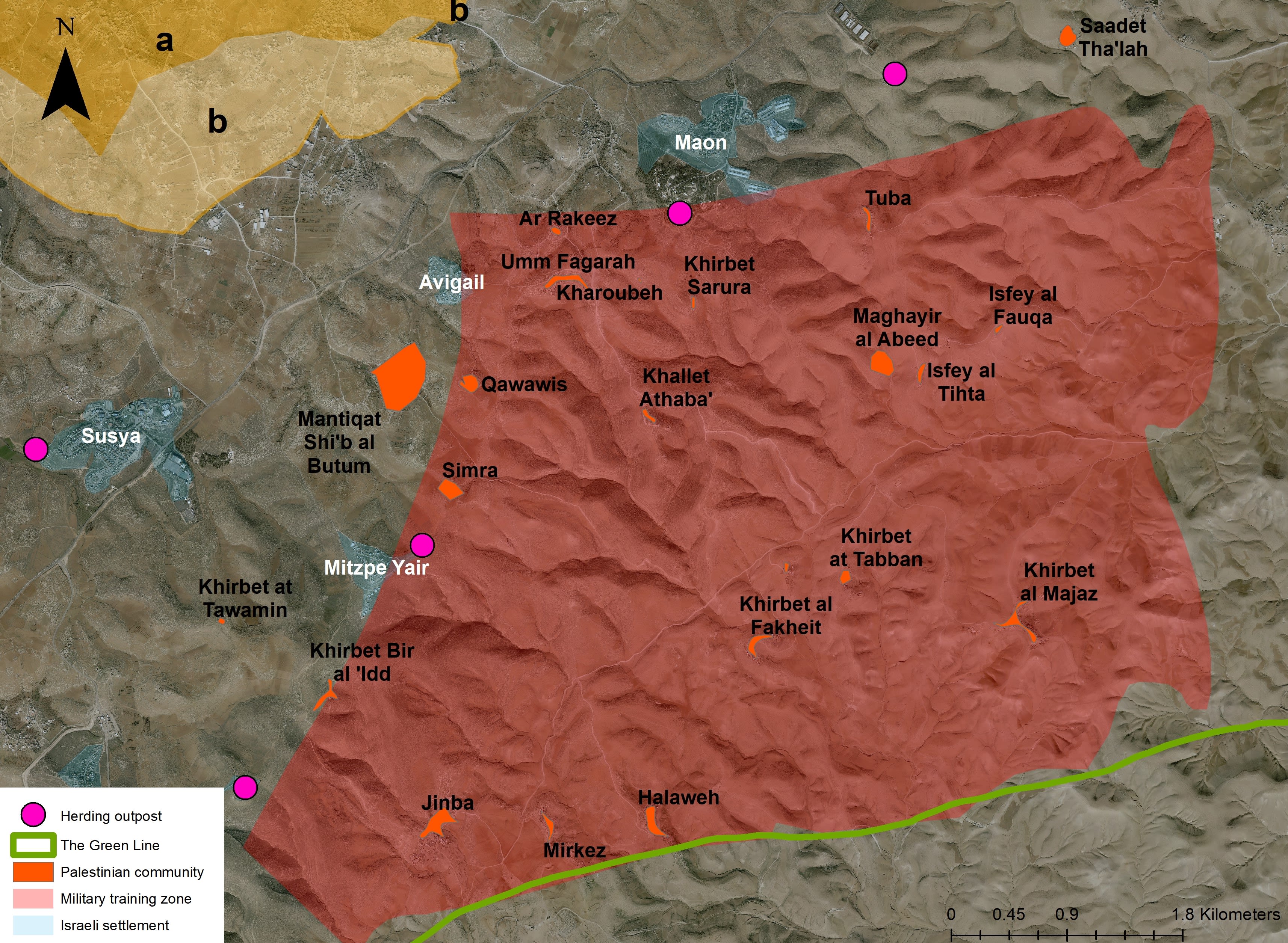

The Israeli army has been trying to drive Palestinians out of Masafer Yatta, an area in the West Bank’s southern Hebron hills, for at least 40 years, since declaring most of the area a closed military zone.

The restricted area, labelled “Firing Zone 918” by the Israeli army, covers 7,400 acres of privately-owned Palestinian agricultural land and encompasses 18 Palestinian communities.

Two of these communities, Kharoubeh and Khirbet Sarura, have been largely abandoned since 2000, when violent settlers drove the families out. Since 2017, attempts to re-establish the Khirbet Sarura community have been blocked by the Israeli army.

Approximately 1,200 Palestinian residents of the other 16 communities in the firing zone are subject to daily Israeli military restrictions and repressive policies. These undermine the residents’ physical security, lower their standard of living, and increase their poverty levels and dependence on humanitarian aid.

That aid – from the European Union (EU), ten of its member states, and the United Kingdom – has made it easier for Palestinian residents to stay on their land, but is no substitute for sustainable solutions.

The West Bank Protection Consortium is supporting these communities through the provision of material and legal assistance. The consortium was formed to prevent the forcible transfer of Palestinians in the West Bank. It is a strategic partnership of five international NGOs led by the Norwegian Refugee Council, 10 EU donors, the United Kingdom, and EU Humanitarian Aid.

The fate of the Masafer Yatta communities located wholly or partly in Firing Zone 918 has reached Israel’s High Court of Justice, and a ruling remains pending.

Waiting for the next demolition

One early November morning, Farisa Abu Aram, 47, was getting ready for a normal working day tending her family’s sheep and goats, when Israeli forces arrived to demolish parts of her home.

“They demolished two living rooms, a kitchen and a toilet unit,” says Abu Aram.

The consortium-funded home was built next to the small cave where she, her husband, and seven sons and daughters live in the Masafer Yatta hamlet of Ar-Rakeez.

“The cave was a small space for my family,” says Abu Aram. “We just wanted to expand.”

The same scene played out twice for Muhammad Dababseh, 42, a resident of Khalet Athaba’, whose home was demolished in 2019 and in 2021. Both structures were partly funded by the EU through the consortium.

“I was living with my wife and children in one room at my family’s house. I wanted to expand by building a modest house on a piece of land I own,” says Dababseh.

While most of the older homes in Masafer Yatta have temporary injunctions protecting against imminent demolition, adding any new structures usually leads to immediate removal.

Israel has demolished or confiscated 217 Palestinian structures in Firing Zone 918 since 2011, displacing 608 Palestinian residents. Some 136 of these had been funded by humanitarian donors, according to the UN Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (OCHA).

Firing Zone 918. Map by Dror Etkes.

Firing Zone 918. Map by Dror Etkes.

Since 2015, the West Bank Protection Consortium, with funding from the EU, ten of its member states, and the UK, has constructed, rebuilt, rehabilitated or replaced 268 structures in the area. These include 150 residential shelters and tents, 69 latrines, four schools and two clinics.

The consortium has also constructed 16 kilometres of a water network and rehabilitated some 17 kilometres of roads. Israeli authorities demolished or confiscated 58 consortium-funded structures during the same period.

New rules make it harder to stop demolitions

The looming threat of demolition has been a constant for decades in Masafer Yatta, but the situation has worsened in recent years. Israeli authorities have stripped away legal protections and sped up the implementation of demolitions and confiscations of materials, structures and vehicles through the use of military orders.

“Palestinian communities are not given enough time to collect the needed documents or to challenge the demolition in court,” says Zvi Avni, an Israeli lawyer who works for the Society of St. Yves, a human rights organisation and NRC partner.

Military Order 1797 expedited procedures for the destruction of any ‘new’ structure without a building permit just 96 hours after Israeli authorities deliver a notice. The order defines ‘new’ structures as those built within six months or inhabited for less than 30 days prior to the issuance of a notice. This has made launching legal challenges much more difficult.

Military Order 1252 and its amendments allow for the seizure of mobile structures—defined as those Israel can dismantle or remove without destroying, such as caravans used as classrooms or residences—without prior notice within 90 days of their construction or delivery, while tools and materials can be seized at any time without prior notice. Since 2016, Israel has confiscated 32 mobile structures in Firing Zone 918.

In April 2021, data acquired from the Israeli Civil Administration (ICA), the branch of the Israeli Defence Ministry that administers the military occupation, showed a dramatic increase in the use of Military Order 1797 across the West Bank, from just 19 instances in 2019 to 134 in 2020.

Between 2017 and 2021, according to Israel's Deputy Defence Minister Alon Schuster, Israeli authorities issued just 33 building permits for Palestinians living in Area C, which comprises 62 per cent of the occupied West Bank, including Masafer Yatta, and is home to around 300,000 Palestinians.

Attorneys now have fewer ways of protecting Palestinians seeking legal reprieve, Avni explains.

EU and European government-funded structures have not been spared in the recent surge in demolitions. In response, NRC and its partners are helping to replace the structures that Israel demolishes and confiscates. They are also involved in funding the legal cases challenging both demolitions and forcible displacement in Masafer Yatta.

A different approach

Other residents have taken a different approach to remaining on their land.

Ashraf Al-Amour, 38, has been living in a cave with his family for years. “When we built residential structures next to the cave, we received demolition orders. But I am challenging it legally,” Al-Amour says.

Today, he says he has realised that his only chance to stay on his own land is to accept living in a cave.

“It was a strange idea for my wife and children at first. Now we are happy and are making the best out of it,” he says.

Military training zone or land grab?

The Palestinians who live in Masafer Yatta argue that declaring most of the area as a closed military training zone was merely an excuse for Israel to take over their land.

They point to the fact that apart from one training exercise held in February 2021, the Israeli army has not held any such manoeuvres in the past eight years, barely justifying such an all-encompassing designation.

Jibreel Hushiyeh, 74, of Mirkez village, witnessed the most recent Israeli military training exercise in early 2021.

“It was taking place between the hills behind our community,” says Hushiyeh. He did not see the soldiers, but says he heard non-stop explosions from tank shells and other live fire.

In the early 1980s, after the area had been declared a firing zone, the army often blocked the main entrance to his village and forced the cancellation of school for days on end as part of its exercises.

“These years we see them less. They don’t really need the area for training. It’s a way to steal more land,” he says.

Israel has designated nearly 30 per cent of Area C in the occupied West Bank as “firing zones”, according to the UN. At least 38 Palestinian communities are located within these areas. Many of the communities have been in these areas for decades, before the firing zone designations and even before Israel occupied the West Bank.

Settler violence

Military training zones and home demolitions are only part of the coercive environment Israeli authorities and policies have created for the Palestinians of Masafer Yatta. Israeli settlers, many of them armed, create constant fear in some areas.

Their settlements were excluded from the firing zone, which ends a few metres short of each settlement, but which includes all of the areas where Palestinian villages are located. These settlements are illegal under international law and condemned, by nearly unanimous consensus, by the international community.

In November 2021, Jaber Dababseh, 34, a Palestinian resident of Khallet Athaba’, noticed a strange tent erected next to his neighbour’s empty house. Dababseh called his neighbour, who was taken aback.

“We approached the area and we saw four settlers,” says Dababseh. He noticed that the door of his neighbour’s house had been broken and the windows smashed.

Israeli forces eventually arrived and removed the tent the settlers had erected, but a group of around 60 settlers stayed in the area until 10 pm, according to Dababseh.

“When the soldiers left, the settlers attacked us with live ammunition and three Palestinians were injured,” he says.

Dababseh says that he was too scared to leave his village for a week after the attack.

A few weeks earlier, Israeli settlers had launched another vicious large-scale attack on the nearby village of Umm Fagarah. A group of armed settlers smashed vehicles and destroyed Palestinian structures.

A Jewish settler from the illegal settlement of Mitzpe Yair chases the flock and threatens the shepherds of Qawawis. Photo: Activestills

A Jewish settler from the illegal settlement of Mitzpe Yair chases the flock and threatens the shepherds of Qawawis. Photo: Activestills

In 2021, the West Bank Protection Consortium recorded at least 27 attacks by settlers that resulted in Palestinian casualties or property damage in Firing Zone 918. So far this year, three such incidents have taken place.

According to OCHA figures, there were 498 such attacks across the West Bank as a whole in 2021, compared to 361 incidents in 2020 and 341 in 2019.

A Jewish settler from the illegal settlement of Mitzpe Yair chases the flock and threatens the shepherds of Qawawis. Photo: Activestills

Israeli authorities rarely arrest settlers for attacks on Palestinians. It is even rarer that settlers face any meaningful punishment for their violence, according to data published by Israeli human rights organisation and NRC partner Yesh Din. Out of 60 settler violence cases tracked by the organisation between 2017 and 2020, not a single indictment was filed.

The EU, ten of its member states, and the UK, through the West Bank Protection Consortium, provide material humanitarian responses to the Palestinian victims of settler violence and support their access to legal recourse.

Much-needed infrastructure

Those Palestinians who manage to stay in Masafer Yatta despite the threats by Israeli authorities and settlers must also contend with structural violence that targets their most basic human needs.

Masafer Yatta’s 18 communities in Firing Zone 918 are scattered throughout arid hills and linked together by rough dirt roads. Some 20 kilometres from the Dead Sea, and abutting the armistice line that separates the West Bank from Israel, these Palestinian hamlets have for the most part never been provided with many of the basic trappings of modern life.

Most of the residents get their power from solar panels, almost all of which are funded by international donors. There is no formal water infrastructure.

In 2018, the West Bank Protection Consortium and the Humanitarian Fund (the emergency pooled fund for the occupied Palestinian territory, managed by OCHA) co-funded the construction of a water network for the communities in Firing Zone 918, at a cost of 136,000 euros.

A concrete drainage pipe in Masafer Yatta, destroyed by Israeli authorities. Photo: Ahmad Al-Bazz/NRC

The EU, other European states and Australia have funded the water network, though this has not stopped the Israeli army from regularly confiscating or destroying the pipes.

Between 2020 and 2021, the West Bank Protection Consortium installed nearly 16 kilometres of water piping in the area. Israeli authorities have destroyed or confiscated more than 3.85 kilometres of that infrastructure during the same period. This included 3.7 kilometres during one day in November 2020, directly affecting four Palestinian communities.

A concrete drainage pipe in Masafer Yatta, destroyed by Israeli authorities. Photo: Ahmad Al-Bazz/NRC

A concrete drainage pipe in Masafer Yatta, destroyed by Israeli authorities. Photo: Ahmad Al-Bazz/NRC

Ismail Abu Aram, 56, a resident of Isfey Al-Fauqa, was among those who lost their water connection in the incident. “They cut the pipes every ten metres to prevent residents from reconnecting it,” Abu Aram says.

The dismantling of the donor-funded water network took place the day after the community received piped water for the first time.

“Now I pay 400 shekels [109 euros] for water I get by truck. I need four trucks per month for the exorbitant sum of 1,200 shekels [327 euros]. That is a lot of money,” Abu Aram says. The trucks can be confiscated if the Israeli military catches them delivering water in the area, he adds.

“I am always worried about access to water. This is what occupies my mind.”

An act of perseverance

Naim Hamamdeh, of Umm Fagarah, refuses to accept the lack of water and decided to plant several almond, grape and olive groves.

“Olives don’t need to be irrigated in the West Bank. However, in our dry area of Masafer Yatta, I have to [irrigate them] to keep them alive in summer,” says Hamamdeh.

Hamamdeh planted his first olive grove eight years ago. Today, he has 15 dunams (3.7 acres).

“Financially, it’s not a profitable project to be created here, but I feel happy to maintain my land,” he says.

Three years ago, his community was connected to a water network for the first time. The new water pipes, however, do not reach all of his orchards, and he has to transport water with his tractor and store it in wells to irrigate his trees.

“One day, I will be able to reach a stage where I can make a good income, and enjoy freedom in this area, God willing,” he says.