Components of a risk management framework

Counterterrorism and risk management frameworks

Identification

Risks can be grouped into two main categories, external and internal, and many subcategories. A SWOT analysis can used to identify risks, with strengths and weaknesses focusing on internal sources of risk and opportunities and threats focusing on external ones.

Organisations should try to identify all risks, including those associated with counterterrorism measures. Once identified, these should be added to an internal risk register, which should be reviewed and updated regularly to account for any changes in context or environment.

Assessment

Once an organisation has identified and classified its risks in a register, it needs to assess them. This tends to be done by assigning each risk a numerical value, often on a scale of one to five, for its likelihood, impact and sometimes an organisation’s vulnerability to it. The values are then combined to establish an overall score for each risk.

There are various ways of assessing risks objectively. This table shows some criteria for evaluating risk impact and likelihood values. The overall scores for each risk can then be put into a risk matrix to create a concise visualisation of the risk assessment.

Establishing a score for residual risk allows an organisation to assess whether the risks are outweighed by the expected humanitarian outcomes of the activity involved. This assessment can be made using programme criticality tools, such as this one used by the UN. The outcome of this assessment can vary depending on an organisation’s risk appetite, or willingness to accept risk, and its risk tolerance, or capacity to accept risk.

Risk mitigation and programme criticality

Once an organisation has identified and put risk mitigation measures into place for a particular risk—for example, counterterrorism measures—it must then assess whether there are any associated residual risks that it is unable to mitigate. After identifying these residual risks, the organisation must then assess them against its own risk appetite, or willingness to accept risk. One way to assess whether a particular risk might be outweighed by the importance of the activity involved is through a programme criticality framework.

A programme criticality framework is an approach to inform decision making around an organisation’s level of acceptable risk, particularly risks that remain after an organisation has put risk mitigation measures into place. A programme criticality framework can provide a structured process to decision making that evaluates the balance of implementing an activity against the residual risks faced. A programme criticality framework should use a set of guiding principles and a systematic, structured approach to decision making to ensure that activities involving an organisation’s personnel, assets, reputation, security, etc., can be balanced against various risks. Programme criticality frameworks can also help an organisation weigh residual risks against commitments to humanitarian principles, particularly those guiding who the organisation assists, and the principles of humanity and impartiality.

In the current context, many donors are pushing implementing organisations to programme in very difficult areas while also maintaining a no-risk expectation. In most of the humanitarian contexts where humanitarian organisations operate today, these two expectations are increasingly at odds and have forced practitioners to try and develop more systematic approaches to navigating these dilemmas. If an organisation has already implemented all of the risk mitigation measures it deems feasible, but it is left with residual counterterrorism risks, the next step could be for the organisation to develop a programme criticality framework.

English: Example criteria for calculating risk impact and likelihood values

English: Example risk matrix

Arabic: Example criteria for calculating risk impact and likelihood values

Arabic: Example risk matrix

French: Example criteria for calculating risk impact and likelihood values

French: Example risk matrix

Monitoring

Approaches to monitoring risk vary, but organisations tend to do so every quarter or trimester. They may also carry out ad-hoc monitoring if a specific trigger occurs. Risks related to specific programmes should be monitored throughout the programme cycle and discussed at programme review meetings.

Reporting

Reporting on risk management should form part of the wider reporting processes that cover an organisation’s overall direction, effectiveness, supervision and accountability.

- Direction: providing leadership, setting strategy and establishing clarity about what an organisation aims to achieve and how

- Effectiveness: making good use of financial and other resources to achieve the desired humanitarian outcomes

- Supervision: establishing and overseeing controls and risk management and monitoring performance to ensure an organisation is achieving its goals, adjusting where necessary and learning from mistakes

- Accountability: reporting to on what the organisation is doing and how, including reporting to donors

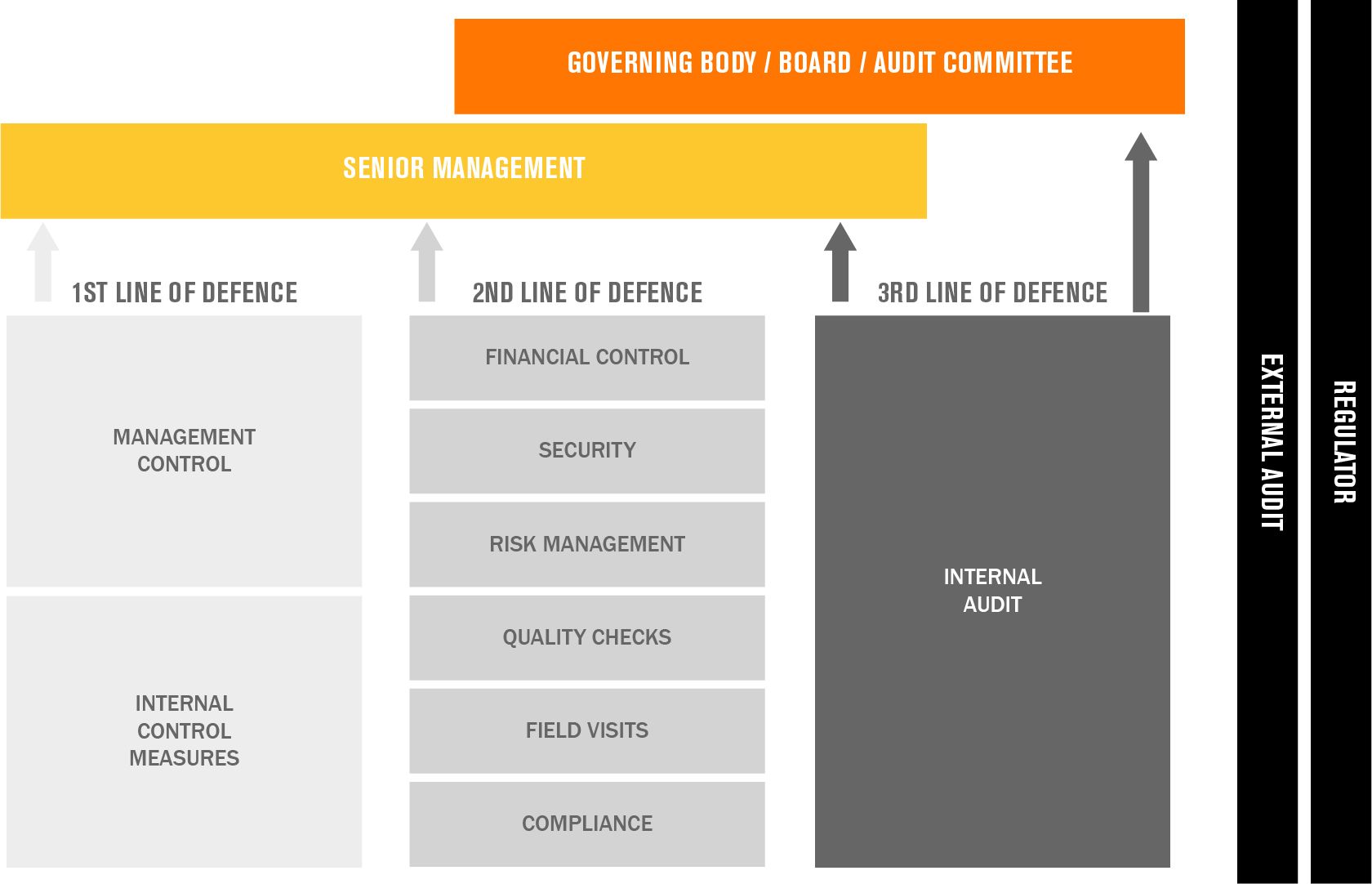

Three lines of defence model

“Three lines of defence” model is an example of a widely adopted governance model of which risk management is a key component.

Management control and internal control measures make up the first line of defence; the various risk control and oversight functions established by management make up the second; and independent assurance makes up the third. Each of the three lines of defence plays a distinct role in an organisation’s wider governance framework.

An example application of this model could relate to a specific counterterrorism measure, such as the vetting of suppliers or employees, that would be implemented by staff in field offices. The process would require oversight from management as the first line of defence. As a second line of defence, compliance staff at the country or regional level would conduct spot checks and review implementation. The third line of defence is the organisation’s internal audit team, which provides overall assurance to global management on the effectiveness of internal control procedures through regular audits.

Sanctions compliance programmes

The US government’s Office of Foreign Assests Control (OFAC), part of the US Treasury Department, is primarily responsible for the implementation and supervision of the US government’s sanctions programmes. Its Framework for OFAC Compliance Commitments strongly encourages organisations bound by sanctions regimes “to employ a risk-based approach to sanctions compliance by developing, implementing and routinely updating a sanctions compliance program (SCP)”. The existence and effectiveness of such a programme is identified as a factor in any enforcement proceedings OFAC takes against organisations that may have violated sanctions and can reduce the amount of any fine imposed.

OFAC states that an effective SCP should have five elements, all of which overlap considerably with the components of a risk management framework:

- Management commitment: Senior management should give compliance functions sufficient resources, authority and autonomy to manage sanctions risks and promote a culture of compliance in which the seriousness of sanctions breaches is recognised.

- Risk assessment: Organisations should conduct frequent risk assessments in relation to sanctions, particularly as part of due diligence processes related to third parties, and develop a methodology to identify, analyse and address the risks they face.

- Internal controls: Organisations should have clear written policies and procedures in relation to counterterrorism-related compliance, which adequately address identified risks, and which are communicated to all staff and enforced through internal and external audits.

- Testing and auditing: Organisations should regularly test internal control procedures to ensure they are effective and identify weaknesses or deficiencies that need to be addressed.

- Training: There should be a training programme for employees and other stakeholders, such as partners and suppliers.

The UK’s Office of Financial Sanctions Implementation (OFSI), part of the UK government’s treasury, performs a similar role. OFSI advises organisations to:

- Understand the scope and coverage of UK financial sanctions.

- Assess all aspects of proposed projects/activities to identify whether any potential third parties are sanctioned entities.

- Tailor the organisation’s compliance approach to the likelihood of dealing directly or indirectly with sanctioned entities.

- Consider other linked types of financial crime, such as terrorist financing or money laundering.

- Where risks are identified, conduct thorough checks of all points in the payment chain for project activities and of those involved in the project on the ground.

OFSI’s compliance and enforcement model has four elements:

- Promote compliance by publicising financial sanctions.

- Enable compliance by providing guidance and alerts to organisations to help them fulfil compliance responsibilities effectively.

- Respond to non-compliance consistently, proportionately, transparently and effectively.

- Change organisations’ behaviour through compliance and enforcement action, which will take account of measures being taken to improve future compliance.