Cash assistance offers

hope to Gazans in distress

Four mattresses lie on the sandy, pot-holed floor of a one-room shack. The walls and roof are made of corrugated metal sheets.

There is no indoor plumbing, piped water or gas for cooking. When night falls, candles and a flashlight – whenever batteries are available – offer the only sources of light amid the darkness.

Since 2018, Majdolene, 28, her husband, Ahmad, 40, and her eldest, Joumana, 4, have called this place home. They live in the slum neighbourhood of Nahr Al-Bared, in the southern Gaza Strip town of Khan Yunis.

The family has recently grown to include daughters Jouri, 2, and Mira, 1. Ahmad also has a 14-year-old son from a previous marriage who lives with his mother.

Nahr Al-Bared sits on government land. To the south is a large informal dumpsite, to the east a cemetery. While no official data exists, residents estimate at least 45 families – some 500 people from across the Gaza Strip – live in deep poverty in this marginalised neighbourhood, according to local media reports.

NRC works to support refugees and displaced people in over 30 countries around the world, including Palestine. Support our work today

The Khan Yunis authorities say the residents are squatters, and provide only limited services on a humanitarian and informal basis. Unable to pay rent, Majdolene says her family’s financial hardship forced them to set up home on government land.

Residents of Nahr Al-Bared report an intense odour during the day and smoke from burning garbage at night. The landfill lures stray dogs and cats, rodents, snakes, scorpions and insects to the neighbourhood.

“We live by a dumpsite that has rats, other rodents, and scorpions,” says Majdolene. “It is not safe here for my children. I am scared to let them out in case a stray dog chases after them.”

Such conditions raise serious safety concerns. The World Health Organization has warned that “inadequately disposed or untreated waste may cause serious health problems for populations surrounding the area of disposal”.

“Life is very difficult,” says Majdolene. “I have small children, my husband is sick, and only God knows how we manage to live. I long to live a dignified life like any other woman, but at the moment, I bear all the responsibility and I feel mentally tired from everything.”

Majdolene says her husband does not have a job or other work. “I am forced to seek handouts from people,” she says. “God only knows how I manage to get diapers and food like soup and such basic things, and I cannot provide for many other needs.”

Root causes

Israel’s siege on Gaza, now entering its 14th year, its recurrent hostilities with Palestinian armed groups, and the internal Palestinian divide have tipped people here into a downward spiral. Severe restrictions imposed by Israel on access, movement and trade have prevented the private sector in Gaza from assuming its natural role as the main driver of job creation and economic growth.

A proposed plan by Israel to formally annex parts of the West Bank prompted the Palestinian Authority to halt coordination with the Israeli government for six months from May 2020. This meant that it stopped accepting tax revenues collected on its behalf, which constitute two thirds of public revenue. The Palestinian Authority struggled to pay public sector employees on time and in full, affecting nearly 40 per cent of Gaza’s workforce, and rolled back social assistance. Some 80,000 families in Gaza who were registered in the Ministry of Social Development’s National Cash Transfer Programme did not receive their last quarterly payment in 2020.

A slum area of the southern Gaza Strip town of Khan Yunis. Photo: Yousef Hammash/NRC

The global pandemic worsened Gaza’s weak economy and eroded people’s already limited purchasing power and resilience. According to the World Bank, the Palestinian economy shrank by 11.5 per cent in 2020. The income of 38 per cent of Gaza families dropped by half or more, according to the Palestinian Central Bureau of Statistics.

The unemployment rate in Gaza during the final quarter of 2020 was 43 per cent, according to the World Bank, with the poverty rate forecast to increase from 53 to 64 per cent by end of 2020. More Palestinians in Gaza were forced into debt, with a growing number of families facing legal action for defaulting on loans. According to OCHA’s 2021 Humanitarian Needs Overview, an estimated 1.6 million people require some form of humanitarian assistance.

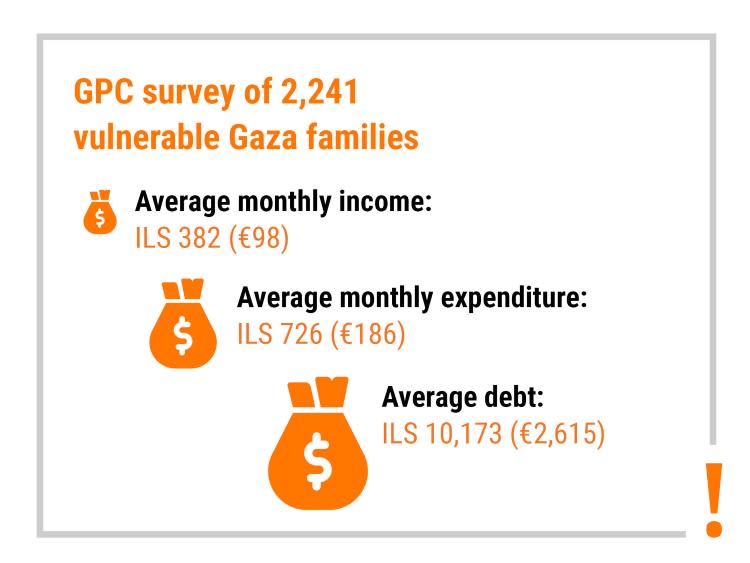

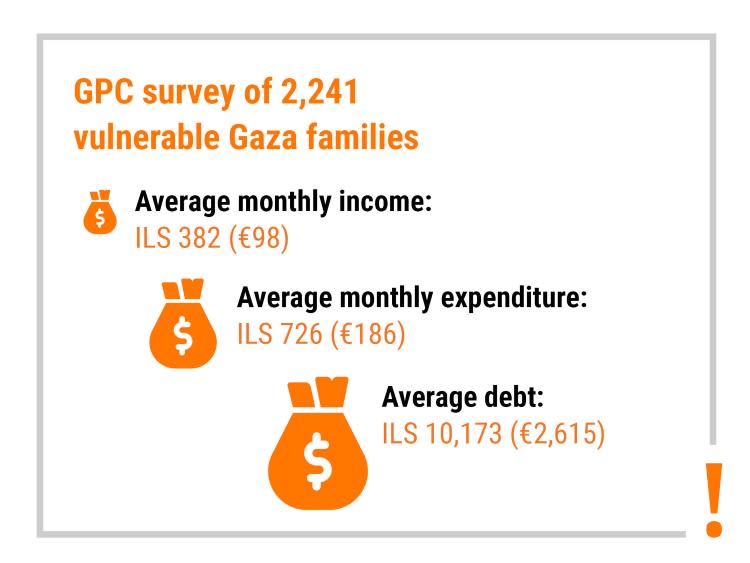

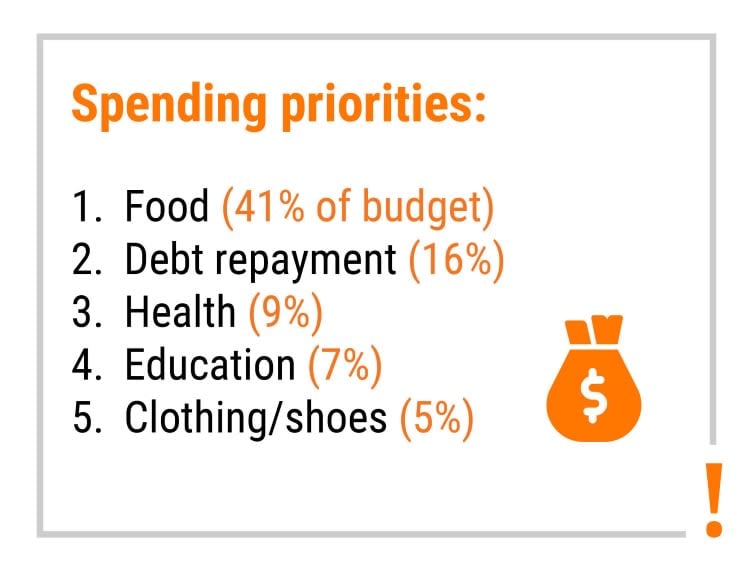

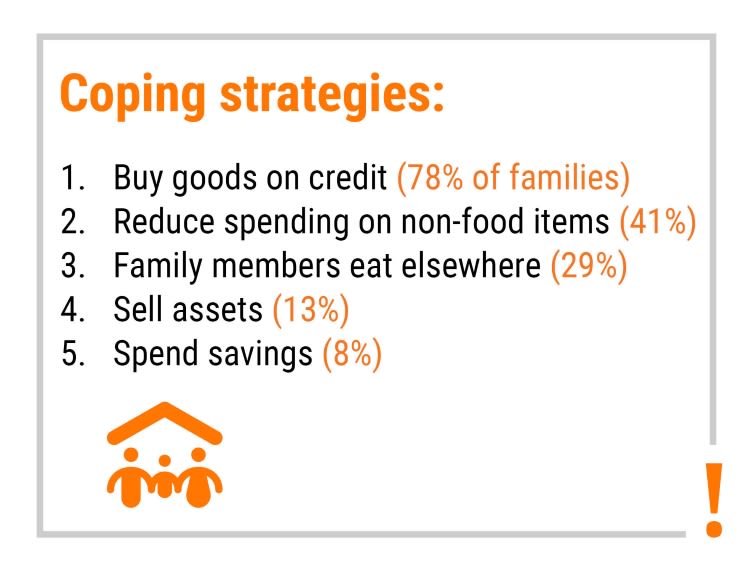

Data from a GPC survey of 2,241 vulnerable Gaza families, conducted in August and September 2020.

Soaring debt

In August and September 2020, the Gaza Protection Consortium (GPC) surveyed 2,241 refugee families, representing more than 14,300 people, across Gaza. The GPC is a joint venture between the Norwegian Refugee Council (NRC) and Mercy Corps, supported by EU Humanitarian Aid.

All the families selected to take part in the survey live in “deep poverty” – i.e. on an income of less than 1,974 shekels (€506) per month – as defined by the Palestinian Central Bureau of Statistics, based on consumption patterns in 2017.

Data from a GPC survey of 2,241 vulnerable Gaza families, conducted in August and September 2020.

Nearly three out of four families reported that they had not worked during the 30 days prior to responding to the survey. Just 22 per cent reported having a temporary job, and only 4 per cent a permanent job.

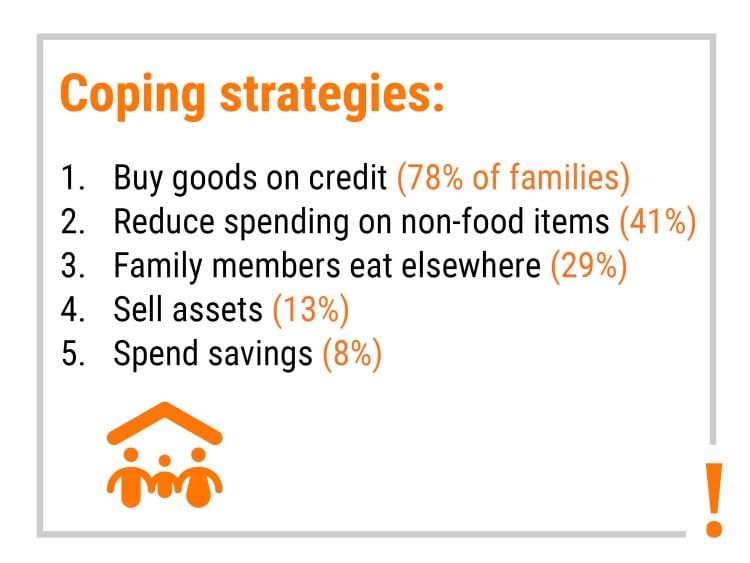

Lack of employment opportunities in Gaza, and the consequent reliance on informal and unreliable sources of income, has driven some 90 per cent of the families to accumulate significant and unsustainable debt.

Data from a GPC survey of 2,241 vulnerable Gaza families, conducted in August and September 2020.

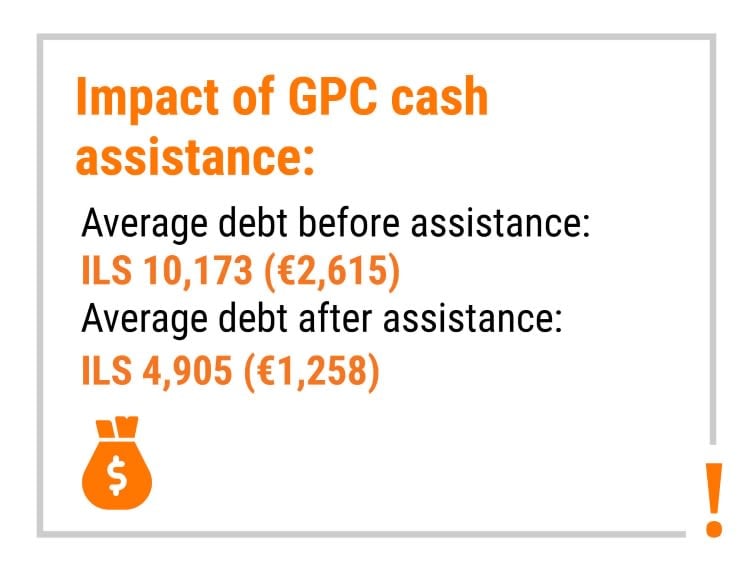

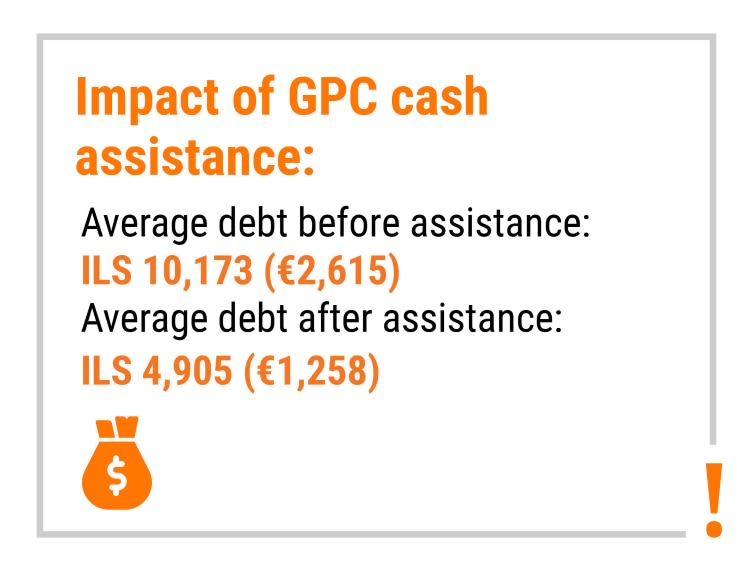

The average monthly income reported by the families amounted to 382 shekels (€98), while the average monthly expenditure was 726 shekels (€186). The average household debt stood at 10,173 shekels (€2,615), equivalent to more than twice the average annual income.

The majority of families said that they resorted to informal borrowing from local shops, family members, friends, other members of the community and employers. Assuming that an average family does not take on new liabilities, it would take six years for them to fully repay their debt without assistance.

The European Union and its Member States are the world’s leading donor of humanitarian aid, helping millions of victims of conflict and disasters every year. With headquarters in Brussels and a global network of field offices, the EU provides assistance to the most vulnerable people on the basis of humanitarian needs.

A slum area of the southern Gaza Strip town of Khan Yunis. Photo: Yousef Hammash/NRC

A slum area of the southern Gaza Strip town of Khan Yunis. Photo: Yousef Hammash/NRC

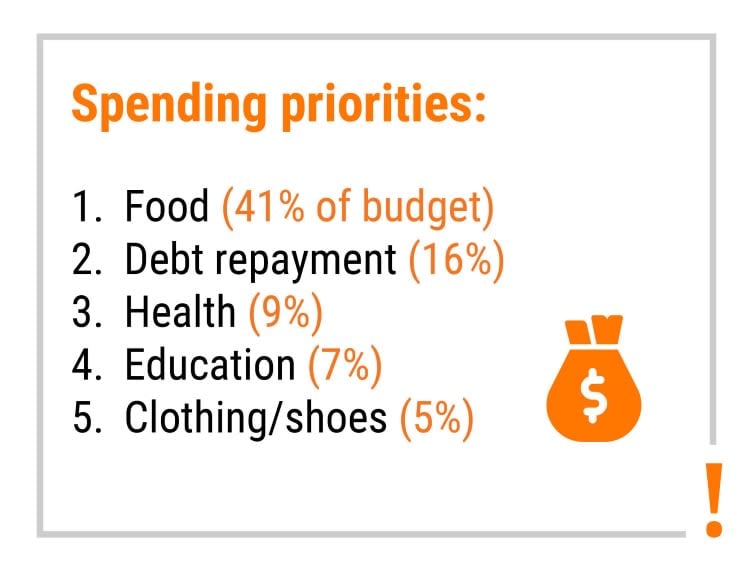

Data from a GPC survey of 2,241 vulnerable Gaza families, conducted in August and September 2020.

Data from a GPC survey of 2,241 vulnerable Gaza families, conducted in August and September 2020.

Data from a GPC survey of 2,241 vulnerable Gaza families, conducted in August and September 2020.

Data from a GPC survey of 2,241 vulnerable Gaza families, conducted in August and September 2020.

Data from a GPC survey of 2,241 vulnerable Gaza families, conducted in August and September 2020.

Data from a GPC survey of 2,241 vulnerable Gaza families, conducted in August and September 2020.

Majdolene says everything they have comes with debt. A friend lent them money to fix the bathroom floor and purchase corrugated metal sheets for the roof. She owes the grocer about 1,200 shekels (€308). She also often finds herself in arrears paying for water to fill the tank the family relies on for domestic use.

A cash lifeline

The high level of debt, coupled with families’ inability to repay, creates a significant source of stress and hardship. A quarter of the surveyed families reported being at risk of imprisonment, and 23 per cent felt unsafe in their community in connection to their debt, presumably due to potential confrontations with lenders.

A previous squatter, who had laid an unofficial claim of ownership over the land where Majdolene’s family lives, has threatened to have Ahmad jailed for not paying him rent. Majdolene and Ahmad had paid him 500 Jordanian dinars (€597) to acquire the plot, but he has since attempted to extort more money from them.

The GPC selected Majdolene’s family and 1,498 others across the Gaza Strip to receive five monthly transfers of 1,196 shekels (€307), starting in October 2020. The families were selected on the basis of vulnerability and comprised some 9,600 individuals in total.

“I was living with the dead,” says Majdolene. “I was running around here and there to find a way to survive, but the grant I received offered a much-needed reprieve from the hands of people who have no mercy… Now, I have the freedom to buy whatever we need and pay off some debts.”

Freedom of choice

The cash assistance is unconditional, and the selected families have the dignity and freedom to choose how best to spend it, using a debit card at any retailer or cash machine.

While Majdolene spends the money on her family’s basic needs, Taraji, 52, uses it to grow her small food business. Since separating from her abusive husband ten years ago, she has raised five daughters and two young grandchildren on her own. They all still live at home in the Khuza’a neighbourhood of Khan Yunis, with Taraji’s eldest daughter, Shatha, 31, moving back in with her two children after a divorce four years ago.

“When we received the grant, we really felt the difference,” says Taraji. “We improved our business a little bit. Now we are able to fill two gas canisters instead of one and cook more food. It took our situation from barely acceptable to quite good.”

Taraji hopes the investment she has made in her business will sustain her family. She continues to supplement her income with embroidery while Shatha, who graduated from university with an English degree, teaches private lessons.

A source of pride for Taraji has been putting all her daughters through university – her youngest still has one more year to graduate. She dreams of getting a bigger home and turning part of it into a kindergarten and nursery, with scope for private lessons, where her daughters can work.

“When a woman is determined to better herself, nothing can get in her way,” says Taraji. “I do not want my daughters to face what I have faced and live my experiences.”

Investing in the home

For Kamel, 36, the five monthly cash transfers allowed him to finish building his home in the northern Gaza village of Um Al-Nasr.

He lives with his wife, their four children, his sister and her three children in a two-bedroom home, with a living room, kitchen and bathroom, on land he bought in 2018 for 6,000 Jordanian dinars (€7,046).

“We can get food. We make do with what we have – a tomato, some tuna, we make it work. But getting a house is difficult to make happen,” says Kamel.

“After I received the grant, we completed the rest of the work. We plastered the walls, laid the floor tiles, did the windows and ceiling. Things began to look up for us,” says Kamel.

The cost of completing the home exceeded the cash assistance and forced Kamel to borrow more money.

“When I completed the rest of the work over the five months, I had to borrow money from people for electricity and water pipes. My debt increased to 8,400 shekels (€2,154).”

Promising results

Post-distribution monitoring by the GPC’s cash experts revealed that 48 per cent of families took on new debt, as the cash they had in hand made it seem less risky and encouraged borrower and lender alike.

However, the data also showed that the average debt for the 1,499 households supported by the GPC had more than halved by the first quarter of 2021, from 10,173 shekels (€2,615) to 4,905 shekels (€1,258). The repayment rate had dropped from six years to 15 months, as families sought to reduce their debt stress.

Some 89 per cent of families reported that their income equalled or exceeded their spending by the third GPC cash instalment, with 98 per cent able to cover all their needs.

Health and wellbeing

Basil, 40, a father of four, lost his job as a construction worker in the southern Gaza town of Rafah when the Covid-19 pandemic struck Gaza. He resorted to borrowing money from his mother’s social assistance to repay debts to lenders who were threatening him with jail time.

“I was depressed. People used to tell me that I did not look alright, and I lost weight because of the extreme stress,” says Basil. “This [cash] assistance saved us.”

Before receiving the GPC’s cash support, Basil’s family used to skip breakfast to save money. “We used to cook lentils most of the time,” he says.

NRC works to support refugees and displaced people in over 30 countries around the world, including Palestine. Support our work today

Before the cash distribution, GPS data showed that 54 per cent of the surveyed families had borderline or poor food consumption scores.

These scores measure and rank the frequency of different food groups consumed in a week. Families were resorting to eating unhealthy and cheaper food, asking for food from relatives or neighbours, limiting portion sizes and reducing the number of daily meals.

After the third cash transfer, however, 76 per cent of the families had an acceptable food consumption score and relied less on negative coping measures.

Why cash?

Studies in several countries have found that cash-based assistance provides the most effective and efficient way to meet the needs of vulnerable people. The GPC survey revealed that 83 per cent of families preferred cash over other forms of support. Cash gives people the dignity, freedom and power of choice to spend as they see fit.

It can also boost the local economy by stimulating demand for goods and services. A 2016 review of data from different studies on cash-based humanitarian interventions found that “unconditional cash transfer programmes generated more than $2 of indirect market benefits for each $1 provided to beneficiaries”.

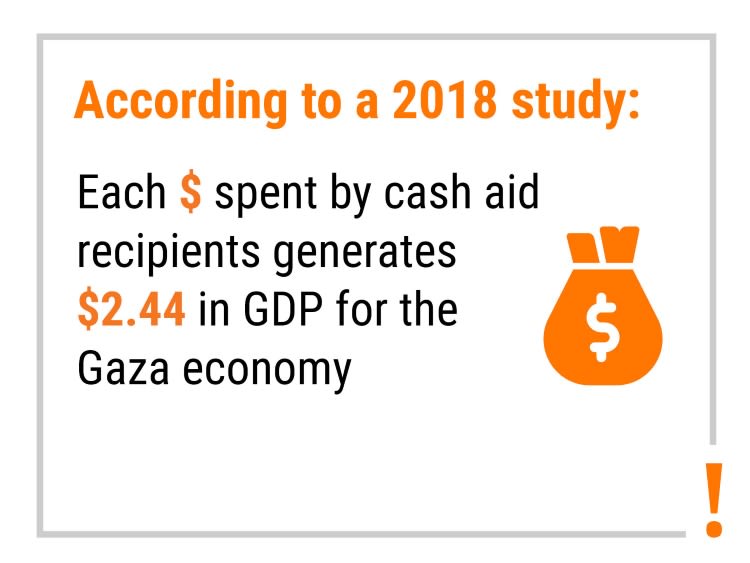

Data taken from a 2018 study commissioned by UNRWA, the UN agency for Palestine refugees.

A 2018 study commissioned by UNRWA, the UN agency for Palestine refugees, likewise reported a significant multiplier effect, with each US dollar spent by cash aid recipients generating US$2.44 in GDP for the Gaza economy.

Data taken from a 2018 study commissioned by UNRWA, the UN agency for Palestine refugees.

Data taken from a 2018 study commissioned by UNRWA, the UN agency for Palestine refugees.

Long-term solutions are needed

The devastating – and preventable – humanitarian crisis in Gaza, compounded by the Covid-19 pandemic and containment measures, has exposed gaps in the social security system. Funding support from donor states is in decline, and thousands of vulnerable families remain on the Palestinian Ministry of Social Development’s waiting list for assistance. Continuation of the GPC’s cash-based assistance programme depends on the willingness of donor states to step up their contributions.

While cash assistance is essential to providing some temporary to medium-term relief for families, it does not offer a long-term solution. Reducing poverty and aid dependency requires significant changes in the policies and practices that shape Gaza’s situation.

These changes include a lifting of Israel’s siege, in line with Security Council Resolution 1860, a long-term halt in hostilities between Palestinian armed groups and Israel, and a resolution of the internal Palestinian divide between rival factions Fatah and Hamas, among others.