Building peace through connectivity

“The strong message I want to give is this: In every country, if there is peace, people can do everything. But if there is not peace, they cannot.”

In the remote town of Akobo in South Sudan, a group of courageous young leaders have rallied together to address issues facing their community. Fed up with the constant threat of violence, inequality for women and girls, lack of education, and isolation, they have taken the lead in enacting change in their community.

Now, they're spearheading a youth innovation project funded by the Norwegian Refugee Council (NRC), driving change, one connection at a time.

The world became one dish

Skype rang. “Can you hear me?” we asked back and forth until the connection became stable. When the image cleared, I was greeted by the bright smile of Duol Kuey, NRC’s ICT Coordinator in South Sudan.

Duol is responsible for providing project support to the young people leading the innovation project.

When we spoke, he was sitting in a newly renovated youth centre in Akobo County, South Sudan. Sunlight illuminated the corrugated walls of the tin shed, providing a glimpse of where local residents spend their time together.

Duol with a group of young people outside the youth centre. Photo: Ingrid Prestetun/NRC

Duol with a group of young people outside the youth centre. Photo: Ingrid Prestetun/NRC

Duol was born in Akobo, near the border with Ethiopia. Located in a remote corner of the country’s eastern wing, Akobo is NRC’s most hard-to-reach location in South Sudan.

Dirt roads frequently punctured by massive potholes limit travel in the dry season.

During the rainy season, the drowned roads transform into mud or even water passageways that are easier to navigate by boat.

During both seasons, the risk of violence looms over each passenger – the space between towns offers no safety.

Although the conflict in Akobo subsided in 2017, sporadic violence between communities continues to take lives. But for many, this remote corner is place of refuge. Returnees, internally displaced people, and refugees travel for days, taking great risks to return to their place of birth or settle into a new home.

Once they arrive, however, many people become trapped and isolated. Flights are too expensive for them to move in and out. And crossing borders is dangerous or nearly impossible, especially without the right documents.

“You could use the Akobo River to get to Gambela in Ethiopia,” Duol explains. “So, it is hypothetically easier to leave Akobo than get to it from within South Sudan.”

Duol’s familiarity with the routes in and out of South Sudan is due partially to his former life as a refugee. “Conflict broke out when I was 16 and I had to spend the next five years out of school,” he explains.

And he was not alone. Duol belongs to an entire generation of young people whose education has been impaired by conflict and a breakdown in educational centres. Finding their way to neighbouring countries, such as Kenya, Uganda, and Ethiopia, many young people try, often unsuccessfully, to complete their education in refugee camps.

Others are able to make their way to the cities, push through enrolment obstacles, and attempt to pick up where they left off. That was Duol’s story. “When it became possible, I went to Gambela and completed a bachelor's degree in Information Technology (IT),” he says.

Nomadic education has been the norm in South Sudan. People expect to travel out of the country to earn their academic credentials.

“Now, due to Covid-19, young people in Akobo have even fewer options. They are stuck here,” says Duol. He believes that education is important not only as an opportunity to learn. “Education is a means of healing trauma. It erases the image of the conflict in this country – of people killing their brothers.”

“That’s why education changed my life. Studying exposed me to many things and different opportunities.”

Studying IT also exposed Duol to the technology that would open up his world even further.

“With technology, the world became one dish. It became one world connected.”

Youth unite

and innovate

That Duol and I are talking online at all is something to celebrate. Six months prior to our meeting, over 200,000 people living in Akobo lacked internet access – a situation that had been going on for four years. With little opportunity to leave and no internet connection, people became isolated – effectively cut off from the rest of the world.

The youth centre where Duol sits now offers the only point of internet connection. This is thanks to the efforts of young people, who – in the face of colossal obstacles – are driving change.

Gatluak is a youth representative in Akobo. With his round, black-rimmed glasses, he looks like a polished university professor as he sits behind the computer.

His wish: to become president of South Sudan. His starting point: working alongside 11 other youth representatives in Akobo for the betterment of the community.

Gatluak sits at a computer in Akobo’s youth centre. Photo: Ingrid Prestetun/NRC

Gatluak sits at a computer in Akobo’s youth centre. Photo: Ingrid Prestetun/NRC

“I carried out many meetings with young people, other youth representatives and local authorities,” Gatluak explains.

“We have a lot of challenges that all youth are facing [in Akobo]. Young people are isolated. There are no jobs. There is violence. And there is a lack of education. The youth are suffering a lot. They are stressed … and even see themselves as meaningless in the community.”

“But also, one of our biggest challenges is connectivity,” he continues. “We don’t have connection to our [friends and family].”

For people living in areas where frequent violence takes lives, knowing your loved ones are safe is vital.

Nyawech Nyoat Banygach, a female youth representative in Akobo, likewise believes communication is vital:

“If you are very far away, it will give you a lot of worries, which can even cause you to be traumatised. But when you have a means of communication, you will be able to know the wellbeing of people, and they will also know of yours.”

Nyawech stands by the riverside in Akobo. Photo: Ingrid Prestetun/NRC

Nyawech stands by the riverside in Akobo. Photo: Ingrid Prestetun/NRC

For Gatluak, Nyawech, Duol and other young people in Akobo, connectivity has been a transformational tool. After engaging in a number of meetings with other youth to express their concerns, they arrived at their first solution – access to internet.

Capturing the youth’s collective motivation, Gatluak took that input and got to work.

“I went to NRC and made a proposal. I asked them to support us – to give us the connectivity, to give us access to the internet – so we could connect to ourselves and others.” His eyes light up, as he excitedly explains: “I am proud of my proposal to NRC. They accepted it.”

In Akobo, young people are generally excluded from decision-making processes. But now, their collaboration and Gatluak’s proposal has given rise to a youth-led innovation project, flexibly funded by NRC.

The youth centre provides internet access powered by solar panels. And a new computer lab helps people get online. University access, job training and research, and speaking with people around the world are now only a few clicks away. The youth centre also serves as place to gather – to break down isolation and connect to one another.

Akobo youth centre. The centre is powered by solar panels. Photo: Ingrid Prestetun/NRC

Akobo youth centre. The centre is powered by solar panels. Photo: Ingrid Prestetun/NRC

Six months on, the youth centre is taking on bigger social issues. And the young people who spend time there view it as a tool to achieve gender equality, as well as a way to build a bridge to peace.

In their own words

In the following chapters, young people of Akobo present a striking image of the issues their community faces and how this project is driving the change they hope to achieve.

A bridge to

peace

Nyawech Nyoat Banygach was born in Akobo. Sitting pensively behind the camera, her gaze wise, she shares her story.

“When the war broke out and the crisis started, we ran to an UNMIS [a United Nations camp] in Juba and stayed there for three and a half years. During this difficult time, I got married. But my father and husband decided for me to come back home to Akobo. I have stayed here until now, but my father remains there. There is no [good] road coming to Akobo. So, the only means is commercial flight, but it is so expensive, and it is impossible for him to get here. That is why he is still there.”

Separated from her family for the last seven years, Nyawech had to reacclimatise herself to an unrecognisable hometown, changed by civil war. Now, even after a signed peace treaty, she still faces the threat of local violence. But as a youth leader dedicated to facilitating peace in her community, she’s bringing people together to change that.

Nyawech and her children. Photo: Ingrid Prestetun/NRC

Nyawech and her children. Photo: Ingrid Prestetun/NRC

“Here we have an issue of [violence], which is very fearful to each and everybody. People also target kids and women,” she explains. “My husband had returned for four years, but he had to leave again due to the threat of local violence. He has been gone for three years.”

Nyawech explains that it is not only this imminent threat of violence that is an issue. There is also pressure placed on young people to take revenge. To kill others when their loved ones have been harmed.

“You can be a young boy, but you will even be influenced to revenge other people for your uncle who was killed. You will not [be able to] live with other people, because when you sit with them, they will just start saying, ‘How can your uncle rest without you rebelling or killing some other person?’”

Heavy hearted, she continues: “If you have a talent to continue with education, it can be very hard, [because people] can deny you your education. They can say: ‘We will not accept your school fees – you stay home until you follow what we tell you because you don’t respect us.’”

Young people are trapped in an “eye for an eye” mentality, often bearing the burden of responsibility when violence breaks out. Not only that – their precious lives become a mark for opposing groups.

Gatluak, who lost his father to local violence, adds: “Rival communities target the youth, especially those who have completed their education, because killing them means doing very serious harm to their families, who have invested in them.”

“The youth centre has given people a place to unite on common ground, providing a place of shared activity to ease tension and build peace.”

Under so many competing pressures and lack of options, young people isolate themselves to avoid the threat of death and the pressure to do harm. But the youth centre has given people a place to unite on common ground, providing a place of shared activity to ease tension and build peace.

“When we come here to the youth centre, we try to [engage] all the clans, those who have intercommunal conflict between each other,” says Nyawech.

“We make peace and reconciliation for those who are traumatised and cannot forget what happened to them or to the people that they love. They come to understand that life is important. And that it is good that they can continue with their life and empower the young generation…, lifting them up instead of continuing with the issue of [violence].”

Nyawech at the youth centre. Photo: Ingrid Prestetun/NRC

Nyawech at the youth centre. Photo: Ingrid Prestetun/NRC

Nyawech also believes that the internet is buying people time to cool down.

When people’s emotions swell and they feel ready to take irreversible action, a video call with family and friends who live in other contexts can change their minds.

Nyawech explains the process: “When you decide to [harm] the other clan, you can communicate with people far away through a video call with people in the outside world, especially if you have relatives in America, or even Kenya and Uganda. They can tell you: ‘You guys, this is not how life should be.’”

Such a lifeline to other people and realities, Nyawech believes, makes internet access a valuable tool for building peace.

“This has [brought] many people together and it has really changed youth here.”

While this project has not eliminated violence completely, Nyawech believes it plays an impactful role in kindling peace. And she hopes to help build a country for her children where it thrives.

“I want to be a peace maker,” she says, “and I also want to be a role model for that.”

Women leaders

rise

“They want to have that capacity and opportunity, but life will keep on neglecting them – since they don’t have that arm to stretch, to make it long or to reach where they want to reach. Every morning and evening that pass by, you would want someone to come grab you and to make a change and twist your story to make it perfect, but that does not happen.”

As a woman in Akobo, Nyawech is all too aware of another issue: pervasive gender inequality. Forced teen marriages, rape, and being denied education afflict many women and girls in the area.

“If you are 13 or 14 years old, your father will just look at you as property. They will just think of how many dowries or how many cows can they get for you. If you are young, you are not involved in [decision making]. So even your marriage can be decided by your father, not you. This is forced marriage,” she explains with fervour.

NRC’s information, counselling and legal assistance (ICLA) project officer, Rhoda, adds: “When it comes to women and girls, we have many cases of gender-based violence, including rape. When women and girls go to collect firewood, they must travel at least two hours from home. We do not have [safe] roads. So, in the middle of cultivation or along the way, they can be attacked.”

Rhoda believes that the youth centre has become a positive place for women to gather and grow stronger together. It has also demonstrated to everyone that accessing the same opportunities enable them to reach the same goals – regardless of gender.

“Female youth are neglected, especially in rural areas,” says Duol, a committed advocate for women’s equality.

“And women in general are marginalised. There is a belief that women cannot do the same as men. Women are often not included, because they must stay home as housewives. Daughters must stay home and get married for cows or money. Being treated like this causes women to think they cannot do something better. This trauma has become a culture.”

In Duol’s view, the youth centre is helping to change that.

“This trauma has become a culture.”

“When we expose youth [to opportunities] together, they know they are not left behind, that they can do just as well. And now there are women at the centre, thanks to our female mobilisers doing local outreach. They are a model to the community. Now [other women] know they can join a school or do business.”

Nyadhiel Biel works with NRC as a mobiliser. She travels to nearby villages to tell others about the youth centre, internet access and online education.

Nyadhiel was born in Akobo but fled with her mother to Kenya to complete her secondary education. When they thought the conflict had ended, they went to South Sudan’s capital, Juba, to work. But when conflict broke out again, they found their way back to their hometown.

NRC mobiliser, Nyadhiel Biel. Photo: Ingrid Prestetun/NRC

NRC mobiliser, Nyadhiel Biel. Photo: Ingrid Prestetun/NRC

“The life I have been through and how I have spent my years, suffering and no-one supporting us, it has encouraged me to be a strong woman,” she says. “Now when I came here, I got this job, which is helping me to help others in the community.”

In this role, Nyadhiel takes on a double task. She informs people of opportunities but also encourages women to join.

Nyadhiel speaking with a group of young women in the community. Photo: Ingrid Prestetun/NRC

Nyadhiel speaking with a group of young women in the community. Photo: Ingrid Prestetun/NRC

“In our village and in our culture, it is very different from others. Some husbands do not want their wives to go in public, and some do not want their wives to study. The only option is sitting at home unless members of your family talk to your husband and tell him the benefits of studying online and the benefit of knowing others,” she explains.

“We can interact with their husbands when we meet them… we tell them about the internet, what is good. Some of them allow their wives to go, because it is very hard for them to get a chance like that.”

Nyadhiel's role as a mobiliser has changed how she views herself.

“I started seeing myself as a person, because the work I am doing makes me a better person. I see myself as a good leader because I communicate with others in good ways. And I think my work has impacted the community because… I go and encourage them. The work I am doing, people respect me,” she says.

Rhoda teaching Nyadhiel how to use a bike to make her community mobilising a little easier. Photo: Ingrid Prestetun/NRC

Rhoda teaching Nyadhiel how to use a bike to make her community mobilising a little easier. Photo: Ingrid Prestetun/NRC

“[And this project] has brought change to the community – women have been taught about the internet and some of them even know how to use the phone. Some of them can even use the computers and that is a benefit to the community. I hope to be, in the future, a good mother and a leader to my country.”

By changing women’s access to public life and the way she views herself among others, Nyadhiel is the leader she hopes to be – a role model transforming her community. And importantly, she is working towards goals that she and her peers have defined.

Access to the internet has also helped many women feel more secure.

“The connectivity has helped me to feel so safe, because if I had something happen to me, I can call my friends, my family,” says Tabitha Nyawech Diew, a young Akobo woman who visits the youth centre.

Tabitha says that the Internet helps her feel safer by connecting her with her family. Photo: Ingrid Prestetun/NRC

Tabitha says that the Internet helps her feel safer by connecting her with her family. Photo: Ingrid Prestetun/NRC

She explains that connecting at the youth centre has brought women together to exchange ideas in ways that weren’t possible not before. And like many of her peers, Tabitha also views herself as a leader.

“My big dream is to empower our society,” she says. “And my biggest hope for the future is to support the women and girls, because they don’t have the opportunity to do things on their own. I need to empower them; I need to share ideas with them and sit together and share how we can change our lives.”

Education is the key

Many young people in South Sudan lack educational opportunities. Education facilities have been damaged or destroyed in the conflict.

Today, there is only one university catering to millions of young people, whose ability to travel has been impaired. But by adding internet access and a computer lab to the youth centre, young people have been able to continue their educational journey online.

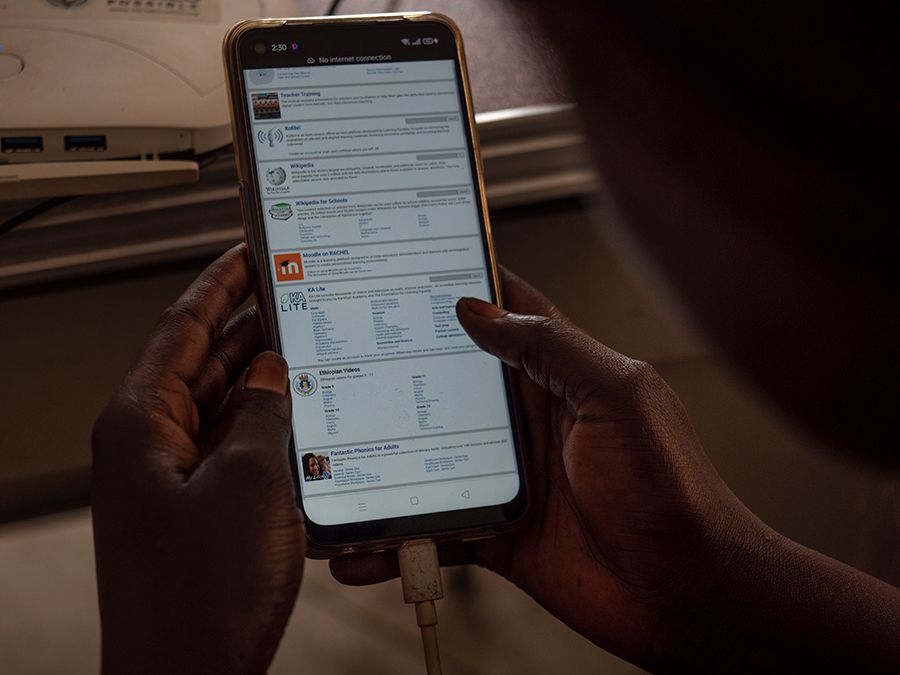

Now young people are attending online courses from the University of Virginia and Distance Education for Africa Inc. (DeAfrica). For days when the internet is unavailable, DeAfrica has provided a remote hotspot device. This enables people to access educational websites and content when they are offline to keep up their studies at home.

The remote hotspot device enables the young people of Akobo to learn, even when the internet is unavailable. Photo: Ingrid Prestetun/NRC

The remote hotspot device enables the young people of Akobo to learn, even when the internet is unavailable. Photo: Ingrid Prestetun/NRC

“We have education online now. We have a Digital Transformation course. We have a Design Thinking and Innovation course, we have a Customer IT Strategy course, we have a Product Management and Production course. We are doing a lot of things. These [courses] help to develop our career,” says Gatluak.

Alongside encouraging other young people to participate, Gatluak has been taking courses online himself. “In December I was awarded a certificate for Digital Transformation. I’m very happy for that. Now I will be studying the Design Thinking and Innovation course.”

There are a variety of other course offerings to appeal to a wide range of educational interests.

Gatluak and other young people view education and career development as the foundation of their efforts to restore their country.

With grounded passion, NRC’s ICLA project officer Rhoda says: “Giving young people and children access to educational training – it is building the structure of South Sudan. It is helping them to solve the conflict that has been happening for so long.”

She continues: “Most of the children under the age of 13, due to lack of training and education, have been dragged in to joining the army. That is not something they do of their own will, but something they are being dragged to do with force. The training that we all get will change that. It is going to engage everyone more instead of them thinking of the conflict and crisis of South Sudan.”

To Rhoda, education is a means of replacing harmful practices with others that are more constructive.

Gatluak believes that if youth in Akobo have the opportunity to develop their skills, they can change the system. “Youth, they are the backbone of their countries,” he urges.

“We play an important role in society, and we are desperate to learn because [youth] are most needed to develop their country. We want to promote peace and development in our communities.”

Gatluak plans to develop another proposal calling for microfinance investments so that young people will have job opportunities after school. “We want the world to know of our skills and to give us [something] to be proud of as youth.”

Connectivity cures isolation

In remote areas, internet access plays an essential role in connecting people to the wider world.

“Before this innovation project, youth felt like they were isolated in a black box. They didn’t know what was going on around the world. Once it started, they had new hope. Different windows opened to give new access to global opportunities,” says Duol.

The young people of Akobo are now connecting. Aspiring journalist Khan, middle, sits with his friends. Photo: Ingrid Prestetun/NRC

The young people of Akobo are now connecting. Aspiring journalist Khan, middle, sits with his friends. Photo: Ingrid Prestetun/NRC

The internet has brought people together. And importantly, it has helped give families living all over the world the opportunity to reunite.

“Different windows opened to give new access to global opportunities.”

Tabitha frequents the youth centre regularly to engage in online courses and chat with friends. But before she started with those activities, she used the centre to resolve a heart-pounding problem.

“Before there was no internet. There was no connectivity. It was difficult for everyone in this community. Especially for those who were separated from their children, their husbands, and their families, like me,” she recalls.

When the conflict broke out in South Sudan, Tabitha was in the city of Malakal. Her husband had travelled to Juba. As a mother, she was worried. She had no way to contact him. “He didn’t know if I was alive, and I didn’t know if he was alive,” she says. In the midst of this mystery, she returned to Akobo to avoid the increasing violence in Malakal.

When the internet arrived in Akobo, she was able to make an important connection. “I talked to my husband’s friend,” she explains. At that time, I didn’t know how to use a smart phone, and he used to tell me to go to the youth centre to connect to Facebook in order to find him.”

“That’s how I got [my husband’s] contact. We spoke and he was safely out of Juba. Now he has joined me in Akobo. I was so happy. At the time when we were separated, I had only one child. And now I have two and he is with me. It is important.”

Khan Banguot Gok is a local author and aspiring journalist, who contributes to a Facebook page called Akobo TV. There he posts news of Akobo to keep people up to date on the latest events.

NRC’s innovation project has been important for Khan’s digital media reporting and ambitions. But also, it has connected him face-to-face with youth in the community he had never previously met.

This innovation project enables Khan to build new friendships and reach towards his ambitions. Photo: Ingrid Prestetun/NRC

This innovation project enables Khan to build new friendships and reach towards his ambitions. Photo: Ingrid Prestetun/NRC

“This project impacted me in many ways. First of all, it connected me with other youth that I did not sit with, because they might stay in a place I cannot reach,” he explains. “Once I came here, I met many new people, chatted with them and built new friendships.”

At the youth centre, which is one of the only places to meet, Khan has made a new best friend, bringing more joy to each of his days. “Before, if there was no place for us to meet like this place, it might have been difficult for me to make that very important friend that I have now.”

NRC’s ICLA project officer Rhoda agrees. She sees the project as a unifying force, bringing youth together to empower each other.

“To me, this innovation project is a solution,” Rhoda says. “Since the project launched, I am seeing youth coming together. This was not there before. People were doing their own thing, and many of them were engaging in local violence. But now, when you go to the centre, you see that the youth are uniting. Before, the peace was not there. But through this project, it has helped bring peace to South Sudan.”