Forced to flee from Chile

Alfredo was left on his own as a 12-year-old

On 11 September 1973, the presidential palace in Santiago was bombed during the coup against President Salvador Allende’s government. General Augusto Pinochet went on to seize power in Chile.

“The next day they arrested my father. I had no-one else but him. I was left on my own.What would I do? That day, I grew up – in a child’s body, with a child’s mind,” says Alfredo Zamudio.

Around his wrist, he has a bracelet with red, white and black pearls. Reading glasses rest on his nose. He gazes out of the cafe window. Snow. A silent infinity of ice crystals in cloud droplets. An icy, white blanket is settling over the old working-class district of Sagene, in Oslo.

In Arica, there are rarely clouds.

Chile’s northernmost city has a mild, temperate climate with some of the lowest annual rainfall figures in the world.

Alfredo Zamudio, 60, gazes at the snowflakes and says quietly, as if to himself:

“My life was normal until 12 September 1973. That day, my childhood ended.”

He turns around: “Completely without notice.”

Why tell?

A half-full mug of coffee. A plate of leftovers from a vegetarian burger. Also on the cafe table: his black notebook. The one he uses to write down his ideas, thoughts and various concepts on the theme of “dialogue”. On a few pages, he has used a calligraphy pen to create meticulously shaped words and expressions such as: “You have to listen to understand”.

This year, NRC turns 75 years old. To celebrate this, we have dug into the archives and talked to many of the people who have been part of our exciting story. Stay tuned for the coming weeks!

Alfredo is Director on Mission at the Nansen Center for Peace and Dialogue in Lillehammer. He was previously Director of the Norwegian Refugee Council’s (NRC) Internal Displacement Monitoring Centre in Geneva. He has worked for NRC, the UN and the Red Cross.

He looks up:

“I’m telling my story so that people will understand how children feel when they are left on their own. When people demand that children who are alone make rational decisions. It’s difficult to be in such a situation. I had no manual. There is no manual.”

Origins

Alfredo’s father was Alfredo Zamudio Concha. He was a small-scale contractor and specialist in building wells. Father and son lived a few kilometres outside the city of Arica, in a self-built house.

“My grandfather on my father’s side had European ancestry, a mixture of Basque and Italian. Grandfather was born out of wedlock, which was considered a great shame at the time. He had little education and few prospects, but he was hardworking and skilled. He became a mechanic in the saltpetre mines and married my grandmother, who came from a small village in Peru, high up in the Andes. She belonged to the Aymara people, with roots from the time of the Incas. This mixture is typical of our continent.”

“From childhood, I especially remember the beach: mile upon mile of sand, and the Pacific waves rolling in. If we were lucky, we would see small sharks.

“It was like the beach was ‘mine’.

“My mother? I saw her a couple of times during my childhood. My parents divorced when I was two years old. Father never spoke ill of her, and I think that was pretty good.”

“Once, when I was allowed to return to Chile after a long time in exile, I took a taxi through the city of Iquique. The driver looked at me in the mirror and said: ‘I know you’. I answered: ‘I don’t think so, because I’ve just arrived. But maybe you know some of my relatives?’ ‘No, I know you. I know who you are. Your father had a lorry. And it had a funny name: Good-Bye My Money.’

“And it was true. Father’s lorry was always broken, and he spent a lot of money repairing it.

“The driver said: ‘I remember when you were little, and your father drove around with you. You had a huge water tank on the loading platform, where your father would wash your clothes.’”

Socialist newspaper and Batman

“Grandfather worked as a mechanic in the mines. It was hard work. From an early age, Father saw what extreme human exploitation meant. He became a socialist,” says Alfredo.

Alfredo’s first memory of his father as a political person is from when he was seven years old. His father would buy a socialist newspaper for himself and the comic book Batman for his son.

“That was how I learnt to read: socialist newspapers and Batman. But my clearest memory is from 4 September 1970. I was almost ten years old. That was the day that Salvador Allende won the presidential election in Chile. The radio was on. I had fallen asleep while they were counting the results. But then I woke up to my father sitting there, crying on the edge of my bed, saying: ‘We won. We won.’”

“One of the things Allende was elected for was that he said that every child in Chile would receive half a litre of milk a day. I think it must have been the first time in world history that milk was an issue in an election campaign. This was implemented in the schools: the children were given proper milk in addition to powdered milk. Schoolchildren also began receiving protein biscuits, because many Chilean children were malnourished, and their growth was stunted due to vitamin deficiency.

“We played marbles and I was really good at it, and I won some protein biscuits from my friends. Now, I’m 2.05 metres tall. When people wonder why I’m so big, I answer: marbles.”

“It was typical of my father that he was unusually tactless. He was no diplomat. Along the whole of one wall of our house, he had painted the symbol of the Socialist Party – a drawing of the continent of South America with the letter ‘P’ on one side and ‘S’ on the other: ‘Partido Socialista de Chile’. On the other wall, he had written slogans in large letters, such as: ‘Forward comrades’ or ‘Victory is ours’.”

“Do you know what? When Father was allowed to return to Chile after living in Norway for several years, he received a piece of land in compensation. It was similar to the land he had had before, just a little further away. He built a house there. On one side of the water tank he had set up, he wrote in large letters: ‘I'm back’.”

Alfredo Zamudio has taken the train to Oslo from Lillehammer, where he is director of the Nansen Center for Peace and Dialogue. Photo: Beate Simarud/NRC

Alfredo Zamudio has taken the train to Oslo from Lillehammer, where he is director of the Nansen Center for Peace and Dialogue. Photo: Beate Simarud/NRC

“You have to listen to understand.” He tells his story mindful of all the children and young people who are alone today, many of them fleeing war and conflict. Photo: Beate Simarud/NRC

“You have to listen to understand.” He tells his story mindful of all the children and young people who are alone today, many of them fleeing war and conflict. Photo: Beate Simarud/NRC

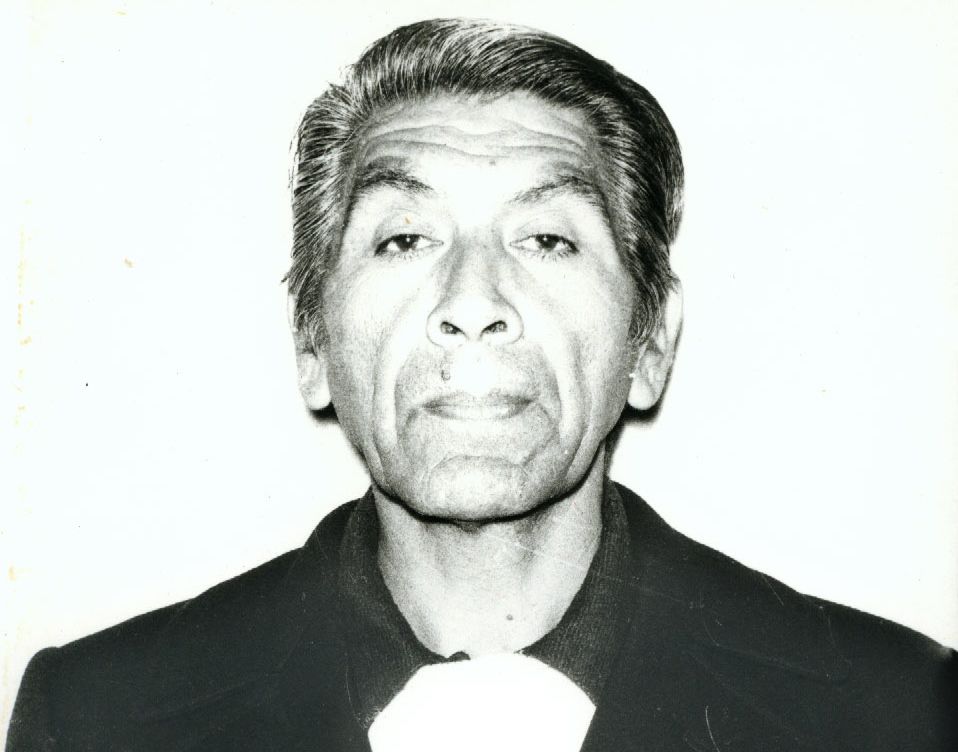

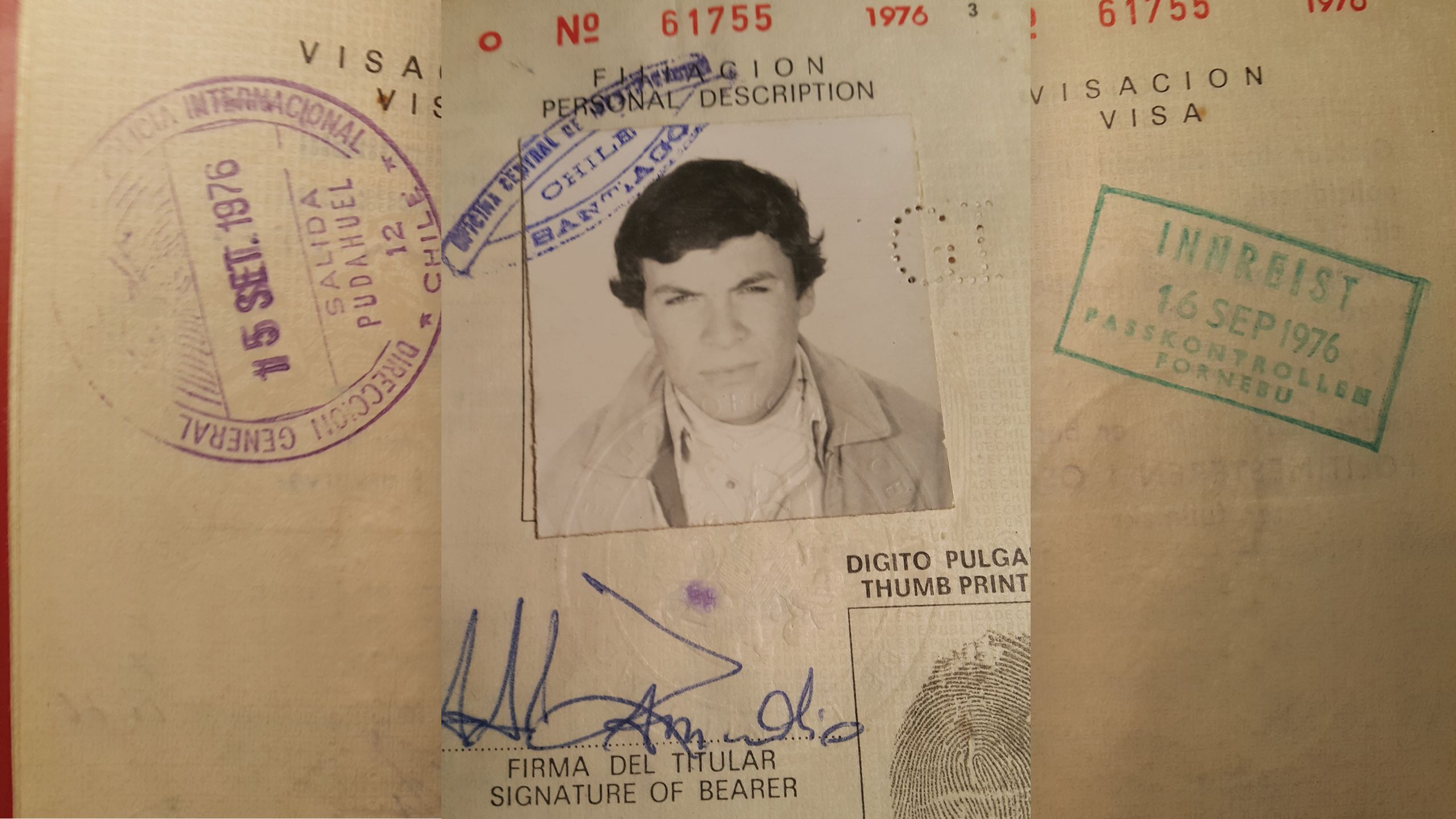

A passport photo of Alfredo Zamudio Concha (1928–1998), Alfredo’s father. Photo: private

A passport photo of Alfredo Zamudio Concha (1928–1998), Alfredo’s father. Photo: private

A touching story about a little boy who had to try to survive on his own. Although it happened many years ago, it’s still fresh in his memory. Photo: Beate Simarud/NRC

A touching story about a little boy who had to try to survive on his own. Although it happened many years ago, it’s still fresh in his memory. Photo: Beate Simarud/NRC

Newly inaugurated president of Chile, Salvador Allende, waves as he walks through the streets from Congress to the cathedral in Santiago, 3 November 1970. Photo: NTB/AP

Newly inaugurated president of Chile, Salvador Allende, waves as he walks through the streets from Congress to the cathedral in Santiago, 3 November 1970. Photo: NTB/AP

“From my childhood, I especially remember the beach. Mile upon mile of sand, and the Pacific waves rolling over it.”

“They’re taking your father”

On the roof was a large homemade antenna so they could watch TV from Peru – the reception wasn’t strong enough for Chilean TV. On 11 September 1973, Alfredo’s father sat in front of the screen and heard the shocking news: the military had seized power.

Employees leave the Chilean presidential palace after surrendering to the military during the coup of 1973. Photo: NTB/AP/Alberto Bravo

Employees leave the Chilean presidential palace after surrendering to the military during the coup of 1973. Photo: NTB/AP/Alberto Bravo

“He seemed worried and wanted to go into town. I think he must have hitchhiked, because we no longer had that lorry.

“The next day my father said, in all seriousness: ‘We have to go to Peru. We will not take the bus, we will walk.’ That would involve a 60-kilometre hike through the desert. I didn’t understand what was about to happen. On the other hand, we had been to Tacna in Peru several times before, to visit friends and relatives, so the fact that we were going there was not so strange in itself.”

Alfredo remembers thinking it was odd that they were going to walk all the way. He wondered how they would manage.

Alfredo’s father told him to go to the store to buy bread and pasta. While he was there, people in the store noticed something happening a little further down the street. One of them said: “They’re taking your father.”

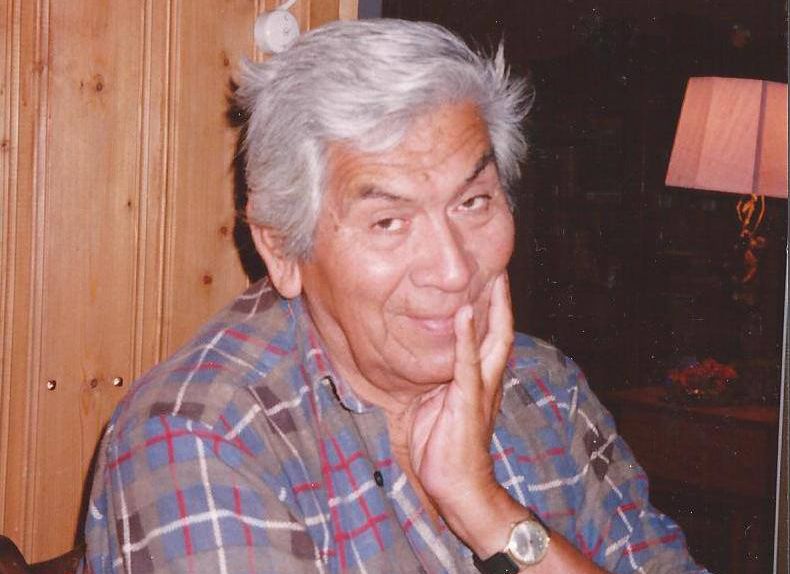

This photo of Alfredo’s father was taken after he had been living in Norway for several years. Photo: Private

This photo of Alfredo’s father was taken after he had been living in Norway for several years. Photo: Private

Alfredo walked down the street towards his house, which was about 400 metres away. He saw a parked car – he no longer remembers if it was a military car or a police car. There were maybe three men on the pavement. A person who looked similar to his father was taken into the car.

“A few seconds later, they drove past me. I saw that there was someone similar to Father in the car. But I could not connect the two things – that it could be my father. My brain simply could not understand what I saw.”

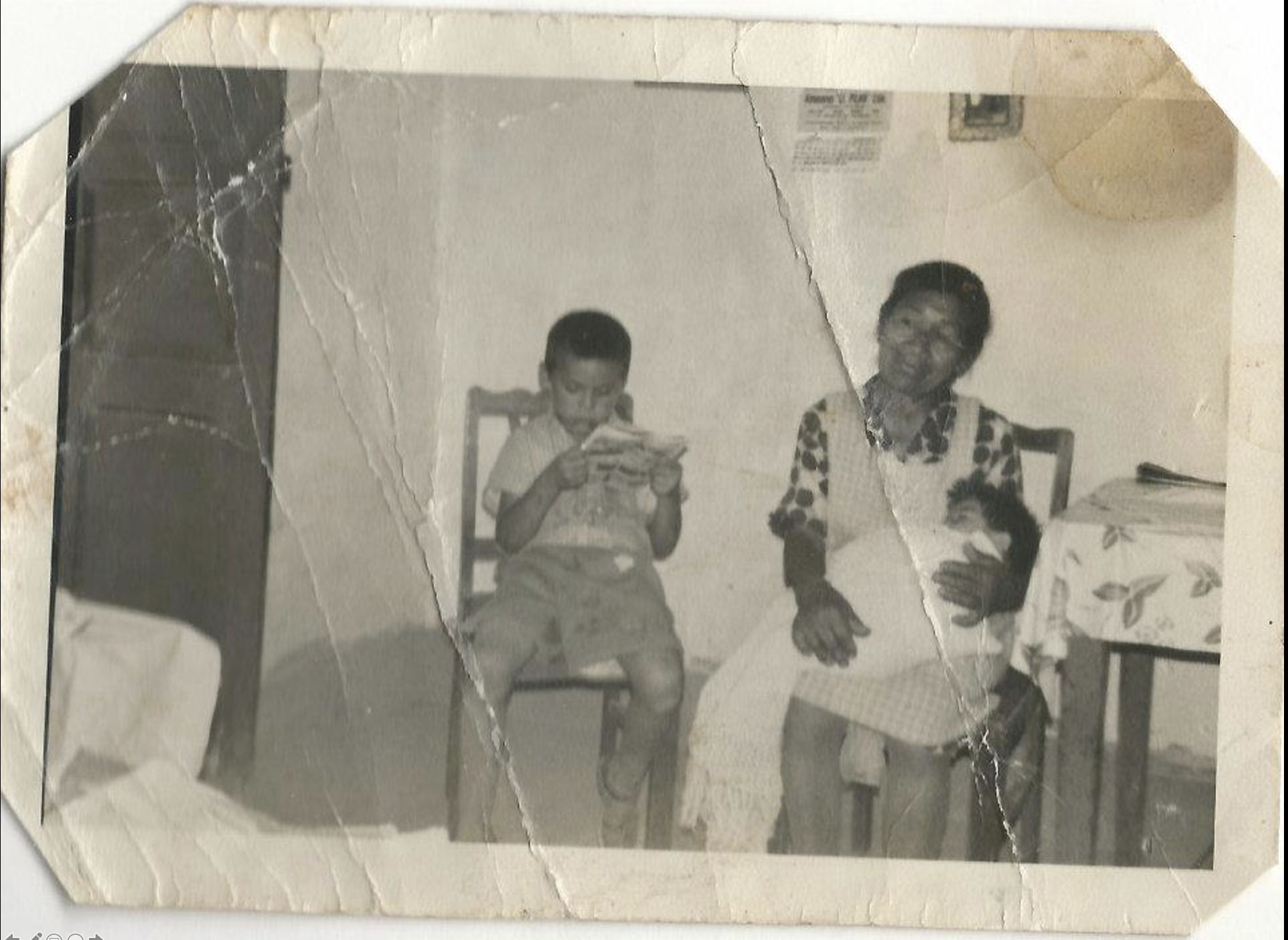

Photo: private

Photo: private

When Alfredo’s father was imprisoned in La Serena prison, he became a kind of all-round caretaker and had the privilege of spending more time out of his cell than the other prisoners. In the yard, he became friendly with a dog. One day the dog was not there. Alfredo’s father became worried and looked around for it. He found his four-legged friend standing in the large square used for the prisoner roll-call. The dog was staring down at the ground – had it gone crazy? It turned out that the dog was staring at ants.

“Many years later, when my father told this story, he laughed. The little creature had given him joy during one of the darkest periods of his life,” says Alfredo, who later got a Chilean artist, Yael Mancilla Gewolb, to make this drawing of his father and the dog.

The North Star

Alfredo walked towards home.

He started to feel anxious.

He opened the door to their house. And he was shocked: their few pieces of furniture had been tossed around. They were broken, and everything looked chaotic.

His father wasn’t there.

“The mattresses were cut up. Father’s shirt was on the bed. I picked it up and smelled it. I smelled him.

“It was the coldest moment of my life. That’s when I understood that he was gone.”

“I tell my story so that people will understand how children who are alone feel.”

He writes down his ideas and thoughts. People from all over the world come to Alfredo and the Nansen Center to learn how to use dialogue constructively.

“Father was my North Star. When I was alone, I often asked myself: ‘What would Father say? What would he do?’ When I was growing up, I had quite a bit of freedom and he trusted me. I could say: ‘Dad, I need books.’ Then he would reply: ‘How many books and how much money do you need?’ As a 12-year-old, I was a pretty independent guy.”

Alfredo didn’t know what to do. His neighbour suggested that he go into the city and try to find out what had happened to his father. He walked out to the main road and hitchhiked. The man who stopped turned out to be one of his father’s arch-enemies in the neighbourhood.

“But he was friendly and treated me nicely.”

Alfredo asked to be let off at Gastón Valenzuela’s house, his father’s friend and a representative in the Socialist Party. Gastón lived in the city centre and was a telegraph operator on the train line from Arica to La Paz. He was 27 years old. Alfredo also knew his wife, because from time to time he received messages from her, asking if he could buy eggs for her from the farms near Alfredo’s home.

“On the TV-screen we could see a lifeless Salvador Allende being carried out of the presidential palace.”

Dangerous times

They let the boy in.

But it was with a certain hesitation.

These were dangerous times.

Soon, another of his father’s friends arrived: Oscar Rippol and his wife.

“I remember the adults sitting in the living room watching the news. They started crying. Because on the screen, we could see a lifeless Salvador Allende being carried out of the presidential palace.

“This reaction from the adults really affected me. But I had no-one to ask what had happened.

“Gastón’s house was a short distance from the governor’s office. We heard military vehicles and tanks rolling down the road.

“I got to stay with Gastón and his wife for a couple of days. During that time, he asked me to help him burn anything that could link him to the socialists: various documents, music records, tourist brochures for China.

“A few weeks later, I met Gastón in the city centre. He was riding home from work on his bike.

“He seemed completely normal. But he was also a careful man.

“A few days later, he was arrested.

“Two days after his imprisonment, I read that Gastón had been shot and killed along with Oscar, in addition to a third person.”

“My father (fifth from the left) stands with the other political prisoners in the prison in Arica. The photo was taken around October 1973, when the local newspaper was invited in by the military to show them ‘the good conditions’. The man second from the right was executed sometime later.” Photo: private

“My father (fifth from the left) stands with the other political prisoners in the prison in Arica. The photo was taken around October 1973, when the local newspaper was invited in by the military to show them ‘the good conditions’. The man second from the right was executed sometime later.” Photo: private

Street kid

Alfredo’s neighbours said that police had been asking for him. He realised that he could no longer live at home. He went to the beach, dug a hole, covered himself with sand and slept there.

During the day he went into the city and knocked on doors. “Can I please stay here?” “Sorry, it’s a bad time.” People didn’t want to take any chances.

The weeks passed.

His father was transferred to three different prisons, and Alfredo followed after to be close to him: first in Arica, then in the city of La Serena and finally in the capital Santiago. Alfredo visited him. Father and son also wrote letters to each other.

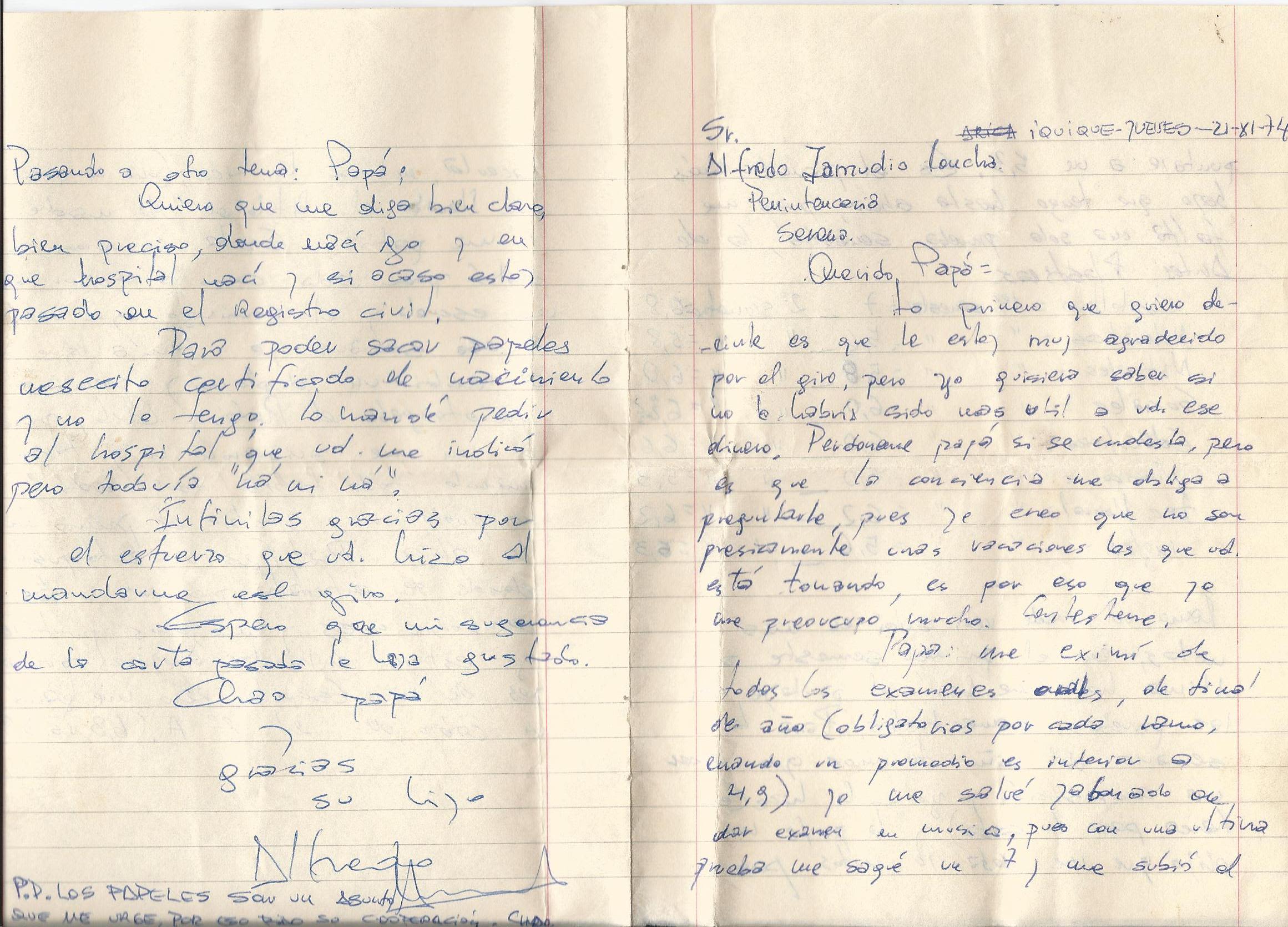

One of the letters Alfredo wrote to his father who was in prison. This is from 1974. A concerned Alfredo writes: “Please do not send clothes to me, Dad. You have better use of clothes than I have.”

(not directly translated)

“I don’t quite remember how, but I got hold of a document that allowed me to visit my father. I had been told that prisoners liked to get cigarettes. So I bought the cheapest cigarettes I could find. The irony is that those cigarettes were called ‘Liberty’. I think it was a blue packet, very similar to the brand that was once advertised with a giant painting on the wall of a building at Majorstuen in Oslo, and which was the brand that King Olav smoked. I liked that painting. Every time I saw it, I was reminded of the packet I bought for Father.”

Alfredo felt great empathy for his father. So, when his father asked him how he was doing, Alfredo would pull himself together, smile cheerfully and say something like: “Great, thanks!”

“One day my father told me to go home and try to sell the TV to make some money. While I was trying to sell the TV to a man, he assaulted me. I was big for my age and hit him. I got away.

“It has always amazed me that paedophiles have such an incredible ability to find vulnerable children.

“I’m not proud to have hit anyone. But I had to. Later I thought: what would have happened if I had not been so big for my age? Or if I had been a less independent child?”

“It was painful to walk barefoot on pebbles all day.”

Child labour

In Arica, Alfredo went to work for a man who ran a small aggregate plant.

“My job was to use a wheelbarrow and sift sand and pebbles. I had no shoes. It was very painful to walk barefoot on those stones all day. I think it took me a couple of days to fill up a lorry. But on my wages, I could only afford to buy a packet of spaghetti. Then I thought: ‘This is no way to make living.’”

“When I visited my father in prison, I saw that he had become very thin. He was about 194 cm and weighed around 60 kg. They had broken his arm. His arm had been previously fractured in the same place in a work accident. He had been operated on at the time. Now, his arm was broken again after a beating from the prison guards when he asked for more food. His arm healed crooked, and there was a deep notch in it. Later, he received an operation in Norway, where the doctors inserted titanium. It was quite funny every time Father went through the security check at airports later in life. He was always ‘beeping’.”

Alfredo was permitted to spend the night at the aggregate plant:

“I slept on the earthen floor and covered myself with potato sacks. That night, I felt a rat coming towards me. And while I was lying there, I heard two men in another part of the room engaging in sexual activity. It was terribly frightening.

“I left when the sun came up.”

Alfredo at NRC

He had never been to Africa before, but in 2005, he travelled to Sudan for NRC. For two years, he worked in Kalma Camp, located in the Darfur region, in the western part of the country. At that time, it was home to about 100,000 displaced people.

While other aid organisations provided services in the refugee camp, NRC’s task was to coordinate it all. Alfredo was hired as coordinator. He was an intermediary between the aid organisations and the village leaders, the sheikhs.

He managed this difficult task by always having an overview of how the camp actually operated. He worked hard to “understand” the camp. The refugee camp had eight teams that reported every day on what was happening. Alfredo and his people used those reports to try to understand the humanitarian needs. This resulted in a good dialogue and good cooperation with the sheiks.

On a mission for NRC in Kalma displacement camp, Darfur, 2006. Photo: Roald Høvring/NRC

On a mission for NRC in Kalma displacement camp, Darfur, 2006. Photo: Roald Høvring/NRC

Alfredo plays with the children in the camp. They line up to be thrown into the air by the tall man. “I remember that I had to be careful when I picked up the children, because they were so thin,” he says. Photo: Roald Høvring/NRC

Alfredo plays with the children in the camp. They line up to be thrown into the air by the tall man. “I remember that I had to be careful when I picked up the children, because they were so thin,” he says. Photo: Roald Høvring/NRC

“I met many very nice and extremely helpful people while I was alone in Chile as a child. During those three years, when I was mostly moving around, I got to stay for seven months with some relatives, where I also had the chance to go to school. That was a great help, and I am very grateful for my time there.

“Others helped me further along my way, helping me to survive. There were also people who said ‘no’ after a while, because they were afraid of the burden. Later, I found my way back to some of those who had helped me. The grandchildren of a lady who was there for me have written and we have had long conversations. They asked me for advice and such, because they have followed my career. Another guy, who also gave me shelter, found me last year. He is an old man now. He still calls me ‘Alfredito’ – ‘Little Alfredo’. I said to him: ‘But I'm not little!’ He answered: ‘To me, you will always be Alfredito.’”

Father’s workmate

One day, as Alfredo was walking down the street in Arica, he met one of his father’s former workmates.

He said: “Come, I have something for you!”

Alfredo was sceptical, but followed.

“I stood in the doorway of his simple house, the walls of which were covered with newspaper. There were some clothes hanging on a nail. He was wearing a miner’s helmet.”

“Father was sentenced to 11 years in prison. But after he had served three years, it became possible to have his prison sentence converted to deportation. In prison, he was visited by the Norwegian ambassador Frode Nilsen. The ambassador recommended Father as a resettlement refugee.

“I was told to get vaccinated and get a passport – I still have that passport. On 15 September 1976, I was to meet up at the airport. I hitchhiked there, which made me a little late.

“Father was surrounded by police officers. He was in handcuffs and shackles, and he had a chain around his waist. When I arrived, he said: ‘You're late.’

“They removed the handcuffs, the shackles and the chain. Ambassador Nilsen took Father by the arm and said to the police: “I'm taking over now.’ Then he led us out.

“My father did not have a higher education and did not know any foreign languages, but Ambassador Nilsen saw that he needed protection and made sure that Norway gave it to him.

“In Norway, we were received by the Norwegian Refugee Council.

“Then our life of freedom began.”

When Alfredo and his father arrived at Fornebu Airport in Oslo, Norway, they were met by a representative from the Norwegian Refugee Council.

“Father’s old workmate walked over to a shirt hanging on the nail. He took money out of the pocket, perhaps the equivalent of 500 Norwegian kroner. I remember that, for him, it was probably a whole week's salary. He handed me the money and said: ‘Take it. Get away from here. Come back one day and show them that they were wrong.’

“At the time, I didn’t understand what he meant.

“But a year ago, at the Nansen Center for Peace and Dialogue, we were asked by the Chilean president if we could assist Chile with conducting talks after the riots in 2019. Since then, a team in Chile and I have, among other things, arranged over 30 dialogue meetings between civil society, the government and academia. We have been asked to continue this work until Chile’s new constitution is ready in 2022.

“My father is dead. But for me, this is a way to repay the many people who helped Father and me in the years when our lives were changed.

“Now I understand what my father’s workmate meant.”