The world’s most neglected displacement

crises in 2021

A display of selectivity

The war in Ukraine has highlighted the immense gap between what is possible when the international community rallies behind a crisis, and the daily reality for the millions of people suffering far from the spotlight.

Each year, the Norwegian Refugee Council (NRC) publishes a list of the ten most neglected displacement crises in the world. The purpose is to focus on the plight of people whose suffering rarely makes international headlines, who receive no or inadequate assistance, and who never become the centre of attention for international diplomacy efforts.

This is the list for 2021.

For the first time, all of the ten crises are on the African continent.

That many African countries are figuring high on the list is far from new. For example, the crisis in the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DR Congo) has become a textbook example of neglect, featuring in this list six times in a row.

Most international media outlets rarely cover these countries beyond ad hoc reporting on new outbreaks of violence or disease, and in several African countries the lack of press freedom is exacerbating the situation. Then there’s donor fatigue, and the fact that many African countries are deemed to be of limited geopolitical interest.

The low level of funding limits the ability of humanitarian organisations both to provide adequate humanitarian relief and to do effective advocacy and communication work for these crises, creating a vicious circle.

Seldom has the selectivity been more striking.

In response to the tragic crisis in Ukraine, we have witnessed an outpouring of humanity and solidarity. Political action has been swift. Donor countries, private companies and the public have all contributed generously. The media has been covering the crisis around the clock. At the same time, the situation is deteriorating for millions of people afflicted by crises taking place in the shadows of the Ukraine crisis.

Hunger levels are on the rise in most of the countries on the neglected crises list, compounded by rising wheat and fuel prices caused by the war in Ukraine. Parents have been forced to cut back on meals for their already malnourished children. Humanitarian organisations have been consistently sounding the alarm since the start of 2022, but the necessary action is yet to be taken by the international community.

On top of this, funding for these neglected crises is under threat. Several donor countries are now considering, or have decided, to reallocate funds from other parts of the world to the Ukraine crisis and the refugee response in Europe.

It is a recipe for disaster. And it will be felt first and foremost by people whose names we do not know and whose stories have gone untold.

Let’s look at what we can learn from the Ukraine response.

The speed at which the UN, the EU and other international partners acted in response to the war in Ukraine should inspire the same urgency for solutions and support to the most neglected crises of our time. Increased awareness about these crises is an important first step towards action.

The methodology

All displacement crises* resulting in more than 200,000 displaced people have been analysed – 41 crises in total. The list was generated based on three criteria, which were given equal weight:

1. Lack of international political will

A qualitative analysis of the international community’s willingness to contribute to political solutions was carried out on all 41 crises. The analysis looked at whether UN Security Council resolutions were adopted, the number and importance of international and government envoys to the conflict, and whether there were any high-level international discussions or other international engagements in, for example, peacebuilding or human rights. The actions taken were analysed in relation to the size and severity of the displacement crisis, and for this we used the FfP Fragile States Index, the ACAPS Severity Index, and relevant displacement figures.

2. Lack of media attention

The level of media attention towards the various crises was measured using figures from the media monitoring company Meltwater, which measures online media coverage. When comparing media attention towards the different crises, we calculated the media coverage relative to the number of people displaced by each crisis, using the latest figures from the UN refugee agency (UNHCR) and NRC’s Internal Displacement Monitoring Centre (IDMC).

3. Lack of international aid

Every year, the UN and its humanitarian partners launch funding appeals to cover peoples’ basic needs in countries affected by large crises. The extent to which these appeals are met varies greatly. The amount of money raised for each crisis in 2021 was assessed as a percentage of the amount required to cover the needs, thus indicating the level of economic support.

*It was not possible to analyse the situation in China and the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea, due to lack of information and reliable figures.

NRC will not ignore these crises. We are responding to the most neglected crises in the world, helping people in desperate need.

1. DR CONGO

The Democratic Republic of the Congo (DR Congo) tops NRC’s neglected crises list for the second year running. Congolese women, men and children continue to suffer in a deafening silence.

In 2021, it took a major geological event, the eruption of Nyiragongo volcano, to trigger some brief international attention to the country. But while the world’s spotlight was on the lava flows, the plight of millions of Congolese in need of urgent assistance across the country remained neglected.

Food insecurity reached the highest level ever recorded, with 27 million people – a third of the country’s population – going hungry. At the end of 2021, DR Congo was home to more than 5.5 million internally displaced people, the third highest figure in the world. A further 1 million Congolese have sought shelter and protection outside the country.

Global indifference

DR Congo was marked by fatigue in 2021. Not from the women, men and children who lived through the daily reality of insecurity and struggle, but from political leaders and the media who once again paid little attention to the crisis. There were no high-level political discussions concerning DR Congo, such as senior officials’ meetings, donor conferences or summits. The absence of strong international political engagement was matched by the lack of media coverage. Of all the 41 humanitarian crises analysed by NRC, DR Congo received the lowest level of media attention when compared to the number of displaced people.

Unprotected civilians

The international community’s inaction compounded its inability to protect civilians. Despite the efforts of MONUSCO, the UN’s peacekeeping mission in DR Congo, the north-east of the country has been continuously plagued by intercommunal tensions and conflicts, with a dramatic increase in targeted attacks on displacement camps since November 2021. Women, men and children who had already fled attacks in their home villages were brutally murdered in the very place where they thought they had found refuge.

Lack of humanitarian funding

The growing level of needs has not been matched by a corresponding increase in support from donors. Only 44 per cent of the 2 billion US dollars required to meet the humanitarian needs inside the country was received last year, and the refugee response remains severely underfunded.

2022 brings more hunger

Food prices are soaring, partly due to the war in Ukraine. Since March 2022, the cost of sugar and cooking oil has risen by 50 per cent, bread by 20 per cent and rice by 11 per cent, posing a huge challenge in a country experiencing historic levels of hunger. Insecurity and violence also persist across the country, leaving little hope for a brighter 2022.

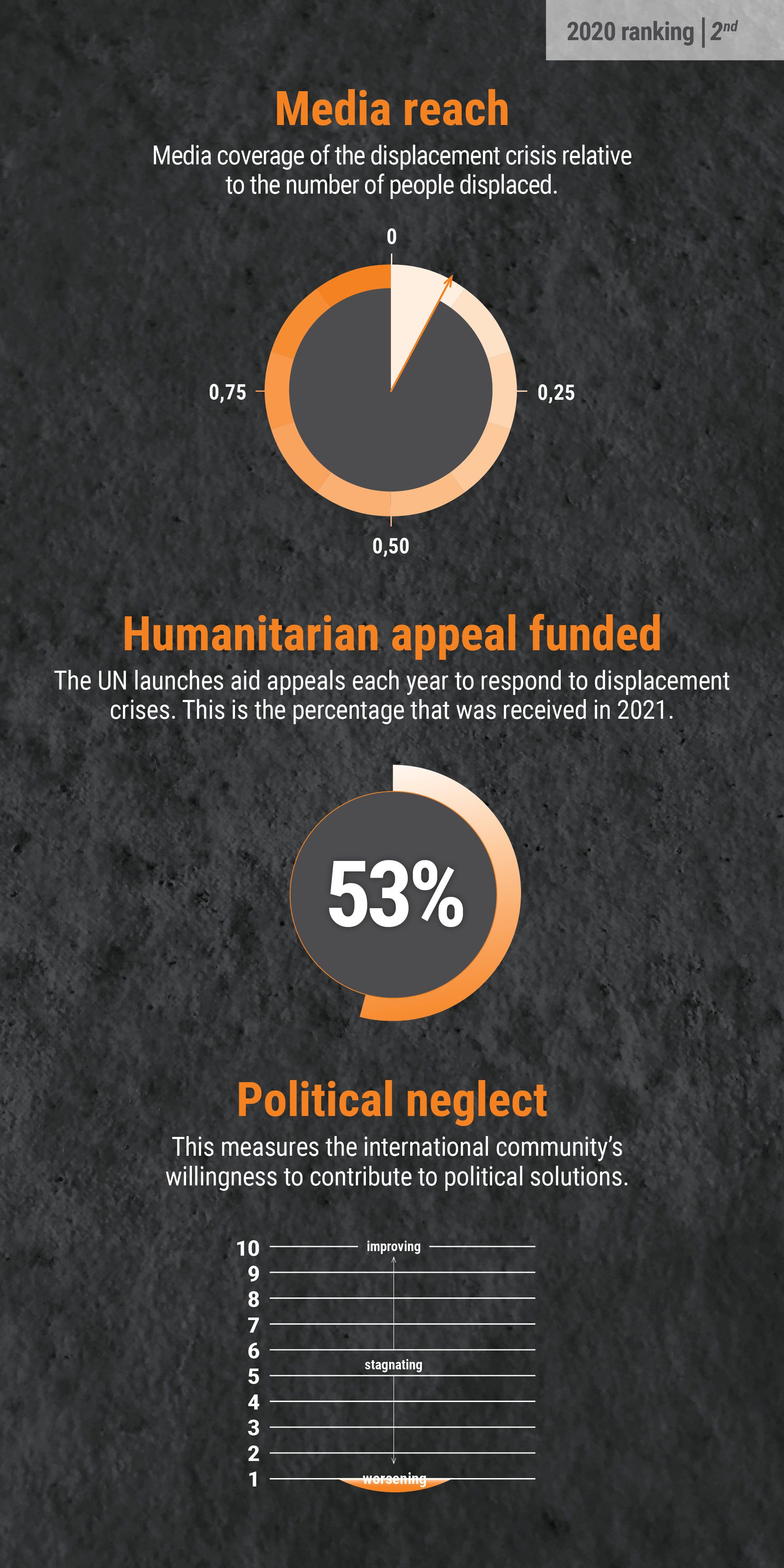

2. BURKINA FASO

Burkina Faso settled into a full-blown crisis for the third year running. After a relatively quiet start to 2021, violence surged once again, leaving more than 800 civilians dead and forcing over half a million people to flee their homes.

The country made international headlines in early June after unidentified gunmen slaughtered over 160 civilians in one night in the town of Solhan, the deadliest single attack in the country to date.

News reporting was otherwise drastically hampered as journalists were de facto banned from accessing displacement sites. Implemented by the previous authorities, this ban significantly contributed to insufficient media coverage of humanitarian issues and a lack of reliable and independent information on attacks and security developments.

Funding of the humanitarian response was less than half of the total needed for the year and fell dramatically in key sectors: for example, only 10 per cent of educational needs were covered in 2021 despite the fact that more than two out of three displaced people in the country are children. Widespread school closures due to insecurity left half a million students without access to learning – a new record in Africa’s Central Sahel region.

With the rate of displacement skyrocketing at the turn of the year and political instability leading to a military coup in January 2022, the humanitarian situation is likely to spiral further this year. The number of displaced is creeping closer to the 2 million mark, while over 3.4 million Burkinabé are expected to go hungry during the upcoming lean season.

NRC will not ignore these crises. We are responding to the most neglected crises in the world, helping people in desperate need.

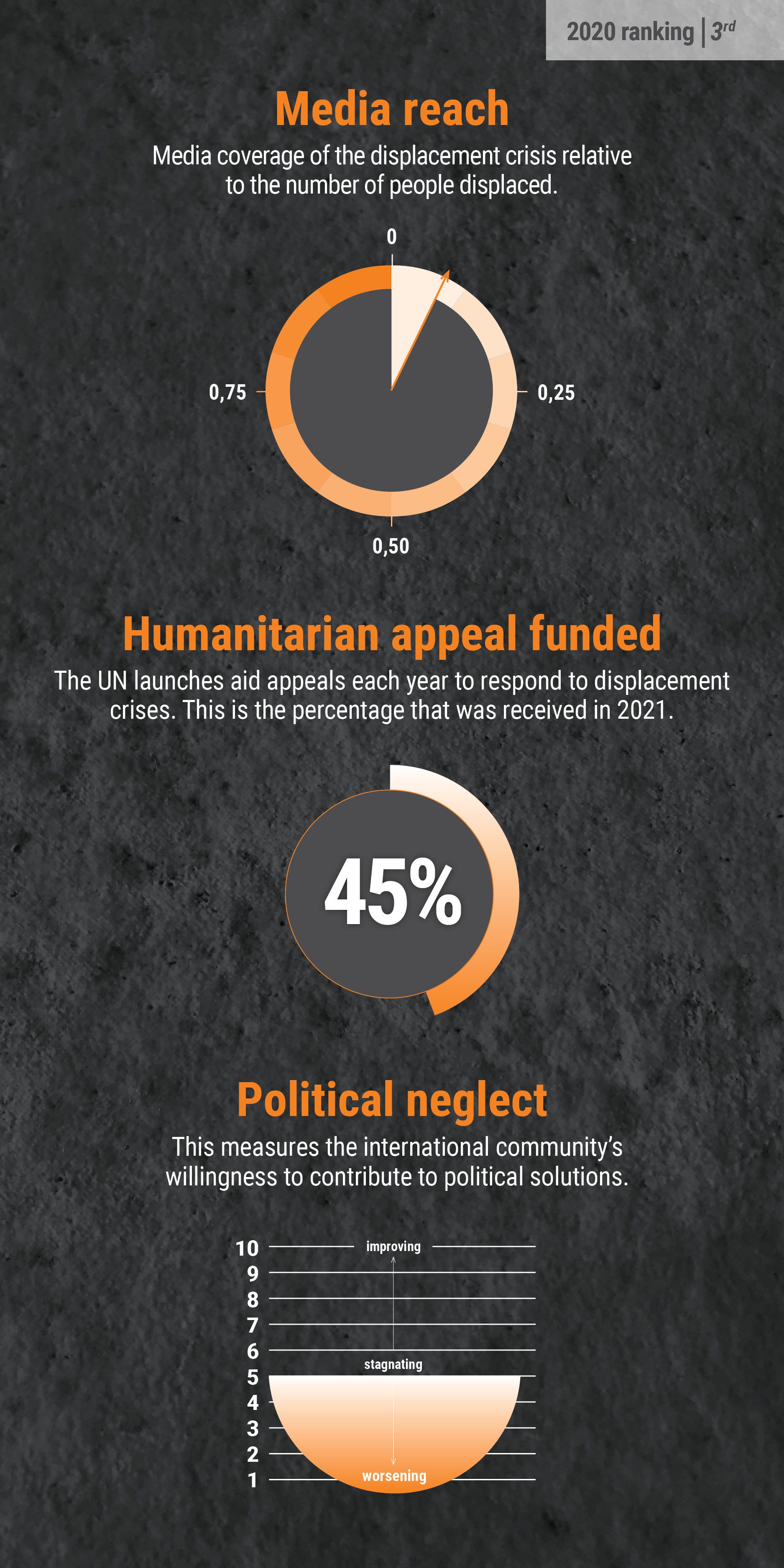

3. CAMEROON

2021 saw three separate crises persist across Cameroon. Widespread insecurity, compounded by climate change and the socio-economic impacts of Covid-19, led to growing humanitarian needs in nine of the country’s ten regions.

The crises left 4.4 million people in need of humanitarian support – almost half of whom had previously been uprooted from their homes. Violence and displacement drove up hunger levels, leaving almost 10 per cent of the population food-insecure by the end of the year.

In the English-speaking regions, growing insecurity and abuses against civilians forced people to flee in search of safety. Attacks on teachers, schools and health facilities continued, leaving 700,000 children unable to go to school.

In the Far North region, violence and attacks significantly hampered humanitarian efforts and access to people in need. Droughts and flooding led to resource shortages, which deepened existing insecurities and drove further displacement. The eastern regions of the country saw an increase in the number of refugees from the Central African Republic, putting further pressure on local host communities.

Cameroon has been ranked in the top three on this list for the last four years due to a consistent lack of political engagement and international attention. 2021 was no different. Aid funding stagnated and international media attention remained limited, in part due to restrictions placed on journalists within the country.

The situation in 2022 shows little sign of let-up for the people of Cameroon, as violence and insecurity persist. The detention of aid workers has led to some organisations suspending their programming, leaving even more people out of reach of aid.

4. SOUTH SUDAN

While the 2018 peace agreement continued to underpin relative stability in South Sudan, widespread violence, ongoing displacement and climate shocks drove growing humanitarian needs in 2021.

A marked lack of international attention, as well as dwindling resources, made it increasingly difficult for humanitarian organisations to support people in need in South Sudan – let alone create the conditions for a sustainable countrywide recovery.

Following a fall in the number of displaced people in the years following the 2018 peace agreement, new displacements meant the number of South Sudanese uprooted from their homes reached 4.3 million at the end of 2021.

The country faced its highest levels of food insecurity and malnutrition since gaining independence in 2011, with the Covid-19 pandemic aggravating the situation for the most vulnerable. A third devastating flood in as many years affected almost a million people last year, not only uprooting people from their homes and spreading disease, but also destroying around 40,000 tonnes of cereals and killing 800,000 livestock.

Slow economic progress and the country’s limited capacity to deliver basic services will mean that creating an environment conducive to the safe return and reintegration of displaced populations will continue to be a challenge in 2022. The ongoing impacts of the floods will lead to an earlier than usual lean season in the first half of the year and widespread hunger across the country, with 8.3 million people predicted to be food-insecure.

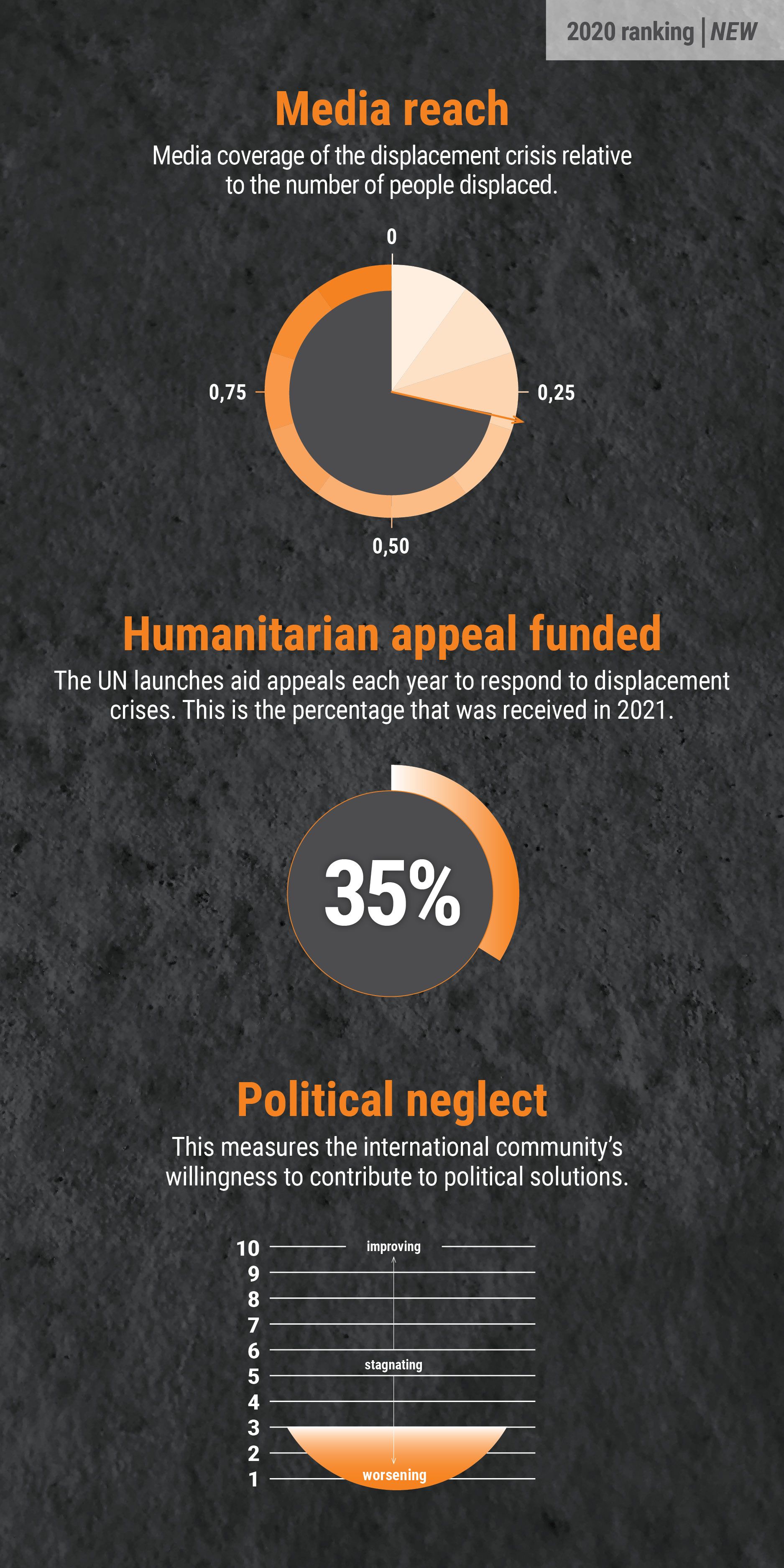

5. CHAD

In 2021, the prolonged humanitarian crisis in Chad continued unabated and conflict escalated. Funding for humanitarian assistance dropped significantly, resulting in more people in need, and bringing the country onto NRC’s neglected crises list for the first time.

A combination of conflict, health emergencies and climate change left around 5.5 million people in need in 2021 – one third of Chad’s population. Hunger and food insecurity levels rose across the country. Children were particularly at risk: both acute malnutrition levels and the mortality rate for children under five years were at critically high levels.

Funding for humanitarian assistance was cut by almost 25 per cent last year when compared to 2020, leading to a limited number of aid organisations operating in the country and inadequate support.

Continued conflicts in both Chad and its neighbouring countries forced people from their homes. In the area surrounding Lake Chad, clashes between government forces and non-state groups, alongside intercommunal violence and climate change, drove displacement. The total number of refugees, internally displaced people and returnees in the country exceeded one million in 2021.

In the political arena, 2021 was marked by the death of President Idriss Deby Itno. Violence flared up in the period that followed, and a transitional military council headed by Idriss’s son Mahamat Idriss Deby Itno took over control, promising an 18 month transition.

A national dialogue was initiated in November 2021, and in early 2022, the military council and opposition groups started talks in Qatar to prepare for national talks. However, the negotiations seem set to drag out.

NRC will not ignore these crises. We are responding to the most neglected crises in the world, helping people in desperate need.

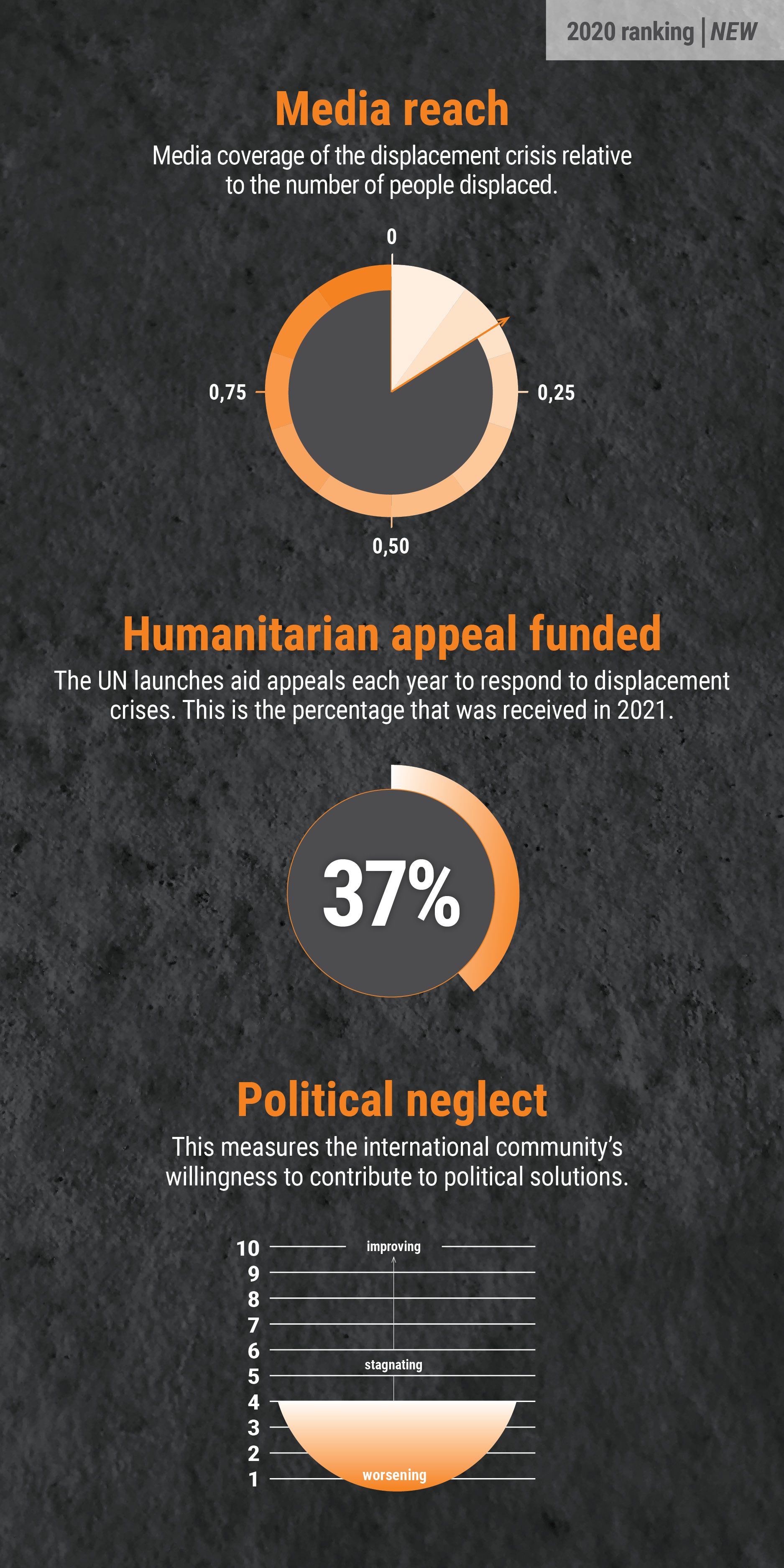

6. MALI

Mali witnessed another military takeover of power, high levels of displacement and an alarming food crisis in 2021, which all contributed to the country’s higher ranking on this year’s neglected crises list.

Food insecurity reached its highest level since the crisis began in 2012, with a staggering 1.2 million people going hungry due to insecurity, drought and the secondary impacts of the Covid-19 pandemic. Attacks by armed groups continued, leaving 350,000 people internally displaced by the end of the year.

Throughout the year, the security situation meant that aid organisations struggled to reach people in need of support. Rising numbers of armed groups, increased criminality, and military operations in the areas where aid organisations were working put both civilians and aid workers at risk.

Despite rising needs, the Malian crisis has gone under the radar of most international media, where the limited coverage has mostly focused on political and military discussions rather than on the plight of civilians. Funding levels were also low, with less than 40 per cent of the humanitarian appeal met.

The international community, including the UN, France and several West African nations, continued to provide military support, but a narrow focus on counterterrorism in the absence of political dialogue has had insufficient effect on protecting civilians.

In 2022, France announced the withdrawal of its troops from the country and a rethink of the counterterrorism plans for the Sahel. The beginning of the year also saw new sanctions put in place, which may have a damaging impact on a country where 7.5 million people are already in need of humanitarian assistance.

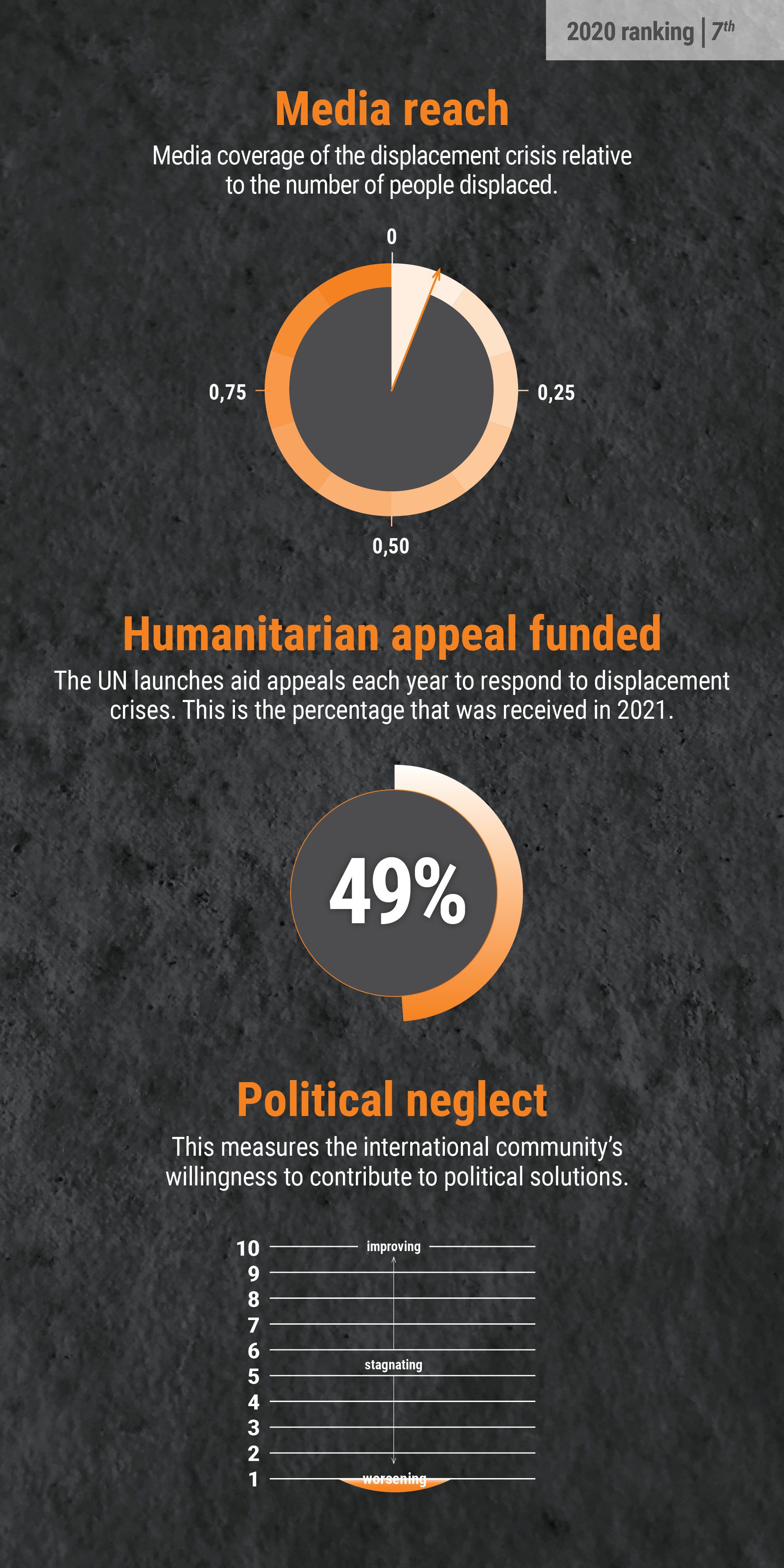

7. SUDAN

In 2021, Sudan experienced soaring numbers of people forcibly displaced, all time high hunger levels and a major political crisis against the backdrop of a sinking economy.

By the end of the year, 14.3 million people were in need of humanitarian assistance. Conflicts over land, resources and the proliferation of weapons continue to be unaddressed.

Over half a million people – mostly in Darfur – were displaced in 2021 alone. This is more than five times the previous year’s figure, and the highest number since 2014. Villages and camps were burned down during attacks. Survivors were forced to flee with nothing and had to find refuge in makeshift camps where they often stayed for months.

In 2021, Sudan also hosted one of the largest refugee populations in Africa. Many refugees received very limited support, and a camp for newly arrived refugees from South Sudan in White Nile State was submerged by flooding.

Hunger levels reached an all-time high, with almost 10 million people acutely food-insecure due to the long-lasting economic crisis, austerity reforms, a difficult harvest and skyrocketing inflation.

The political crisis exacerbated the situation. In November, the civilian-led transitional government was toppled by the military. In reaction, major international donors and financing institutions froze bilateral support and debt relief packages to Sudan. Civil liberties were curtailed, making it harder for human rights defenders and journalists to report on Sudan.

The prospects for 2022 are bleak, and a hunger crisis looms as the number of food-insecure people looks set to almost double by September. The Sudanese people will pay the price of the country’s further isolation from the international community.

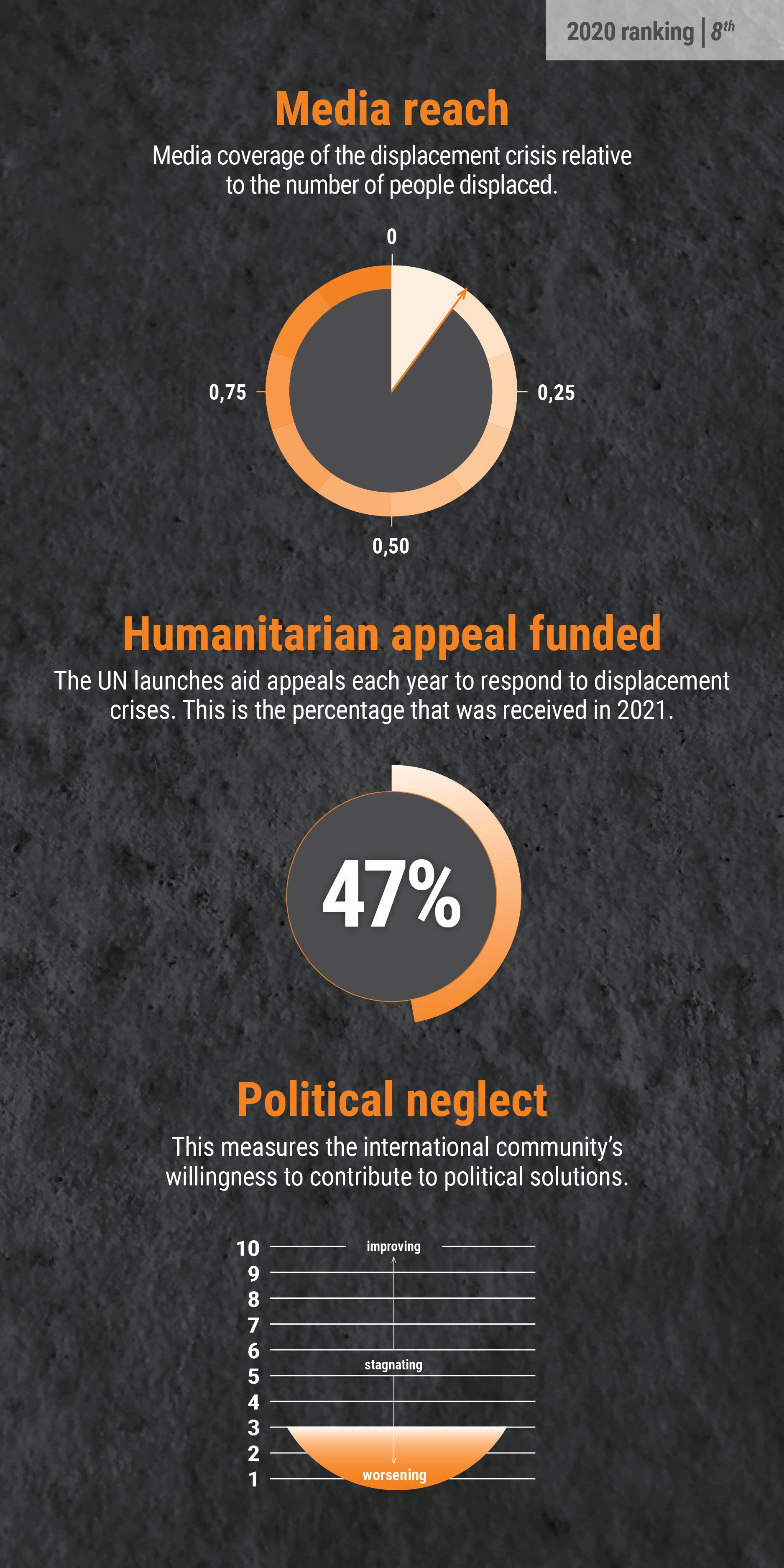

8. NIGERIA

In 2021, the conflict in north-east Nigeria continued unabated. More people were forced from their homes and left out of reach of aid. Meanwhile, in the central and north-west areas of the country, clashes over land and resources, as well as criminality, rose significantly.

Funding for the crisis continued to decline for the fourth year running, despite nearly 13 million people requiring humanitarian assistance.

In the north-east, where the majority of families are thought to face crisis or emergency levels of food insecurity, over one million people remained out of reach of aid organisations. Insecurity meant that humanitarian workers could not travel outside of the city of Maiduguri by road, leaving them heavily reliant on UN helicopters to reach people in need.

2021 was defined by a drive to close all formal displacement camps in Maiduguri and Jere by the end of the year, despite pervasive insecurity and a lack of alternative safe places to live. By the end of 2021, five camps had been closed, leaving 66,000 displaced people searching for a home once again.

The international community continued to neglect the crisis and made very little effort to intervene or remove the barriers preventing the delivery of much-needed aid. Insecurity and a lack of access prevented significant media coverage of the crisis.

In 2022, the authorities continue to implement their plans to close formal displacement camps and return refugees to neighbouring countries. Food security levels are expected to deteriorate in the upcoming lean season, with the highest gap between needs and funding since 2016.

NRC will not ignore these crises. We are responding to the most neglected crises in the world, helping people in desperate need.

9. BURUNDI

In 2021, the situation in Burundi remained fragile and severe human rights violations continued, without generating headlines. Some Burundian refugees living in neighbouring countries felt coerced to return due to harsh policies and a lack of opportunities.

More than 400,000 people fled Burundi in the years following the deadly clashes around the 2015 presidential election. While some have returned to the country, at the end of 2021 more than 260,000 were still living as refugees in DR Congo, Rwanda, Tanzania and Uganda.

Many refugees believe it is still not safe to go home. But life in some neighbouring countries is becoming increasing untenable: refugees are forced to live in camps, unable to work and without access to adequate services. The situation is unlikely to change soon. In 2021, a group of UN human rights experts deplored reports of enforced disappearances, torture and forced returns of Burundian refugees living in Tanzania.

There have been only limited improvements in Burundi’s human rights record since President Evariste Ndayishimiye came to power in 2020. Suspected members of opposition groups continue to disappear, many have been detained and there have been documented cases of torture.

Burundi has appeared on our neglected crises list five years in a row, and the neglect continues. Despite the welcome release of some journalists during the last year, media activities continue to be severely restricted, which partly explains the lack of coverage of the crisis. Funding for both humanitarian needs in Burundi and the refugee response in the neighbouring countries remained poor.

Improvements to international political engagement between the authorities and the European Union, which restarted in 2021, offer an opportunity for much-needed dialogue on the country’s human rights record in 2022.

10. ETHIOPIA

The full-scale conflict between Ethiopia’s federal government and regional authorities in the Tigray region continued into its second year in 2021, resulting in mass killings, sexual violence and widespread displacement and hunger.

In 2021, tens of thousands of people fled Ethiopia to neighbouring Sudan to seek refuge. The ongoing conflict in the north of the country was compounded by instability and violence in several other regions and a devastating drought – leaving almost 4.2 million people internally displaced.

Ethiopia’s humanitarian response plan for 2021 was only 47 per cent funded – a reduction of 11 percentage points from the previous year. Funding failed to match the scale of growing needs, including for the hundreds of thousands of refugees from South Sudan, Somalia and Eritrea who are currently living in the country.

International media coverage of the humanitarian crisis in Ethiopia remained very low and irregular when compared to the scale of the crisis, further deepening the neglect.

On 24 March 2022, the Ethiopian government declared a humanitarian truce, but this has yet to result in any meaningful improvement in aid flows. With extensive humanitarian needs across much of the conflict area in the north, civilians in Tigray continue to suffer from a significant scarcity of food, water and medicines.

Ethiopia now has the highest number of people in need in the world, with a staggering 29.7 million people requiring humanitarian assistance. The number of people estimated to be in need because of the drought increased from 6.8 million to 8 million in April this year.

Conclusions

While each of the ten crises outlined in this report should be given dedicated support and attention, we can draw several broad conclusions across them:

- Once on the neglected crises list, it is difficult for a country to move off it. Out of the ten, seven have featured on the list repeatedly during recent years. This points to a vicious cycle of international political neglect, limited media coverage, donor fatigue, and ever-deepening humanitarian needs.

- The ten most neglected displacement crises this year are all on the African continent. Addressing them will require overcoming donor fatigue, finding lasting political solutions, and reassessing the effectiveness of years of humanitarian response.

- The majority of today’s humanitarian crises are protracted in nature and involve more than one crisis happening at the same time. Across the countries on the list, a disastrous combination of conflict, displacement and recurring climate induced disasters makes humanitarian needs all the more severe.

- Hunger levels are on the rise in most of the countries on this list, an issue exacerbated by rising wheat and fuel prices caused by the war in Ukraine.

- In conflict-affected countries, only lasting peace deals and inclusive political solutions will allow conflict-affected populations to resume or rebuild their lives. Further political efforts – at both national and international level – and humanitarian diplomacy are essential to encourage parties to join, or return to, the negotiating table.

- The lack of media attention towards these neglected crises is compounded by the strict restrictions on freedom of the press in several of the countries on the list.

Recommendations

Although an identical formula will not work for all crises on the list, the recommendations below provide some practical steps to improve the situation for people currently neglected by the international community.

Recommendations to the UN Security Council (UNSC) and member states

- Ensure that neglected or protracted crises across Africa are given adequate attention by the UNSC and relevant bodies. This includes dedicated geographic and thematic meetings, and tabling resolutions where appropriate.

- To help avoid the normalisation of neglected or protracted crises, consider establishing a “Group of Friends” of neglected contexts, championed by one or several UNSC members. This group can push for the appointment of Secretary-General Special Envoys, recurring high-level pledging events, accountability mechanisms, and other initiatives as needed.

- Translate “humanitarian diplomacy” into practice by helping humanitarian organisations overcome barriers to safe and unimpeded access in hard-to- reach areas, negotiate with all parties to a conflict, and lessen the administrative constraints under assertive governments.

- Ensure that counterterrorism measures and sanctions do not unintentionally impact humanitarian organisations working in difficult operating environments and trying to reach those most in need quickly and safely.

- Use your mandate to urge all conflict parties to respect international humanitarian law. Where violations are identified, support international accountability mechanisms.

- Recognising that only an end to conflicts will bring longer-term stability in complex and protracted displacement crises, foster high-level political engagement at national and regional level in support of inclusive political solutions.

- Ensure that the mandate of UN peacekeeping missions across African states – and beyond – is sensitive to humanitarian concerns, adequately resourced, and prioritises the protection of civilians. Close coordination with aid agencies and accountability to local populations is equally important.

Recommendations to donor governments

- Provide humanitarian assistance according to the needs of people affected by crises, and not according to geopolitical interests or levels of media attention.

- Seek to overcome fatigue around particularly complex or protracted crises. Together with a small group of states, lead on organising high-level pledging events or senior officials’ meetings. Beyond financial commitments, these events should also seek to address underlying political causes and identify measurable commitments by parties.

- Increase flexible and longer-term predictable funding so that the humanitarian response can better address overlapping factors, including conflict, displacement, and recurring climate-related disasters.

- Support the ability of humanitarians to work in complex contexts by simplifying due diligence procedures, providing guidance on navigating counterterrorism or sanctions where applicable, and offering more manageable risk-sharing models for aid agencies and local partners.

- Advocate across government for an increase in humanitarian spending, and externally with international financial institutions for complementary funding in humanitarian settings.

- Commit to increasing refugee resettlement quotas to the global north and ensure safe and legal pathways for those fleeing all crises – not just those in the headlines.

Recommendations to journalists and editors

- Invest in quality journalism from underreported crises, beyond news coverage of sudden onset disasters or outbreaks in violence. Inform and stimulate debate, and act as a watchdog.

- If red tape, such as lack of media permissions or visas, hinders reporting from a crisis, use media platforms to advocate for the necessary changes, and explore digital solutions to get first-hand accounts from people on the ground.

- Engage in the protection of press freedom and the safety of journalists to ensure domestic and international journalists working in crisis-affected countries can continue to report.

- Report in a way that focuses on solutions and does not contribute to exacerbating conflicts or stereotypes.

Recommendations to humanitarian organisations

- Provide evidence-based analysis to donors to help shape annual humanitarian aid allocations based on the severity of needs.

- Press for strong humanitarian leadership in country that can engage with national and international stake holders on behalf of the humanitarian community and raise concerns at the highest level.

- Improve coordination between aid organisations on the ground. Optimise the use of resources and avoid unnecessary competition for the limited resources available.

- Invest in advocacy. Often countries that receive the least funding cannot afford advocacy and communication resources, creating a vicious circle and making it difficult to draw attention to these crises at an international level.

- Link up with foreign policy think tanks, research institutions and other organisations that can help approach neglected crises from different perspectives, to collectively press for humanitarian issues to be included in broader policy debates or decisions.

Recommendations to the general public

- Hold your government and politicians to account against aid commitments and policy pledges by writing letters, signing petitions and submitting questions to national parliaments.

- Read up about neglected crises and support quality journalism that covers forgotten conflicts. Speak up about these crises and share the stories on social media.

- When donating to a crisis, avoid giving to the crises that receive most media attention, as this may not necessarily be where your support is most needed. If you can, consider making a recurrent or regular donation.

NRC will not ignore these crises. We are responding to the most neglected crises in the world, helping people in desperate need.