Hour of reckoning for European refugee policy

Refugees stranded at sea are being returned to detention camps in Libya where they live under slave-like conditions. Non-governmental organisations are threatened with fines if they bring shipwrecked refugees to land in Italy. Norway and other countries are sending asylum seekers back to Greece, where refugees are already living under inhumane conditions in crowded camps. What happened to Europe?

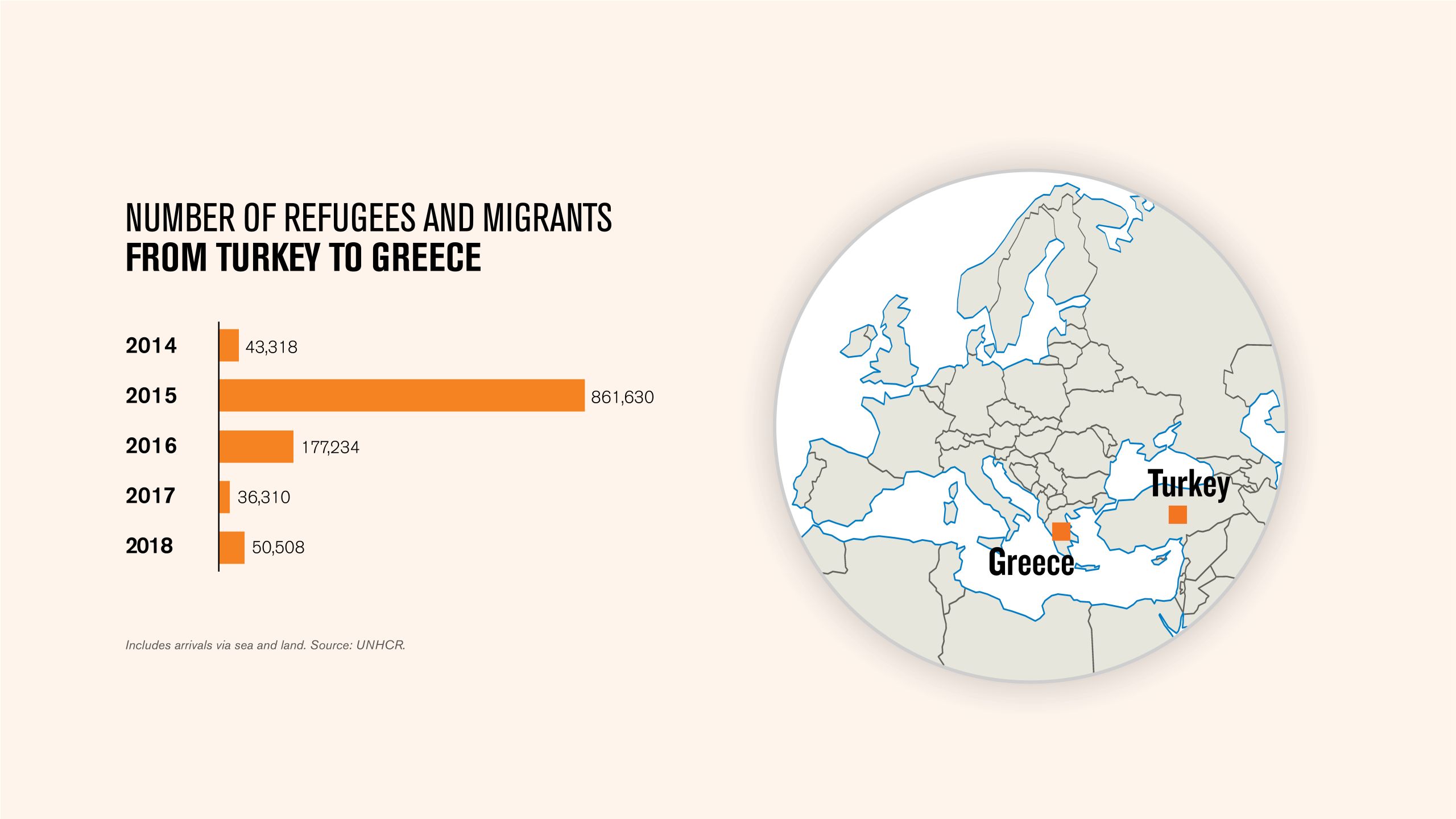

European politicians are struggling to deal with the consequences of the urgent measures introduced after the major influx of asylum seekers in 2015, when more than one million people applied for asylum in European countries. At that time, most came by sea from Turkey to Greece, before travelling further through the Balkans to countries in Western Europe.

Germany and Sweden were the countries that received the most refugees. Both political leaders and public opinion in these countries welcomed the new arrivals at first, but the mood shifted when it became clear that the flow of refugees was showing no signs of slowing. As a result, dramatic measures were introduced.

A woman comforts her injured son on a beach shortly after they arrived with other migrants and refugees on the Greek island of Lesbos in 2016. Photo: NTB/Scanpix (Markus Heine/Nurphoto/REX)

The consequences of the EU-Turkey agreement

The most important measure to limit the number of refugees and migrants was the agreement between Turkey and the EU, negotiated by the German Chancellor, Andrea Merkel. It meant that anyone who arrived in Greece without valid papers would be sent back to Turkey. In return, the EU would accept a corresponding number of Syrian refugees from Turkey. Turkey also received six billion euros from the EU to handle the large number of refugees within its borders. The agreement between the EU and Turkey has led to a decline of over 90 per cent in the number of refugees and migrants arriving in Greece.

Although fewer people are arriving in Greece, the number of asylum seekers there has risen sharply. This is because it has proved to be very difficult from a legal perspective to return refugees and migrants to Turkey, and because the EU now requires Greece to take responsibility for all refugees and migrants who enter the country.

A child wrapped in a survival blanket on the Greek island of Lesbos after having crossed the Aegean Sea from Turkey in 2016. Photo: NTB/Scanpix (Markus Heine/Nurphoto/REX)

In 2015, the EU adopted a temporary relocation scheme for asylum seekers who had come to Greece and Italy, which Norway also signed up to. The scheme was sabotaged by many European countries, and it was not extended when it expired in autumn 2017. In addition, under the terms of the Dublin Regulation, the EU insists that the first European country where asylum seekers come to register their fingerprints should be responsible for the asylum process and provide protection to those who need it.

Greece left to fend for itself

This requirement of the Dublin Regulation was previously practised only to a limited extent, to the benefit of both the border countries within the Schengen Area and refugees themselves. Fingerprints were often not registered in countries such as Italy and Greece, allowing refugees to travel through them to the country where they wanted to apply for asylum. There was also a certain understanding from countries in other parts of Europe that it would be unreasonable for a few countries to receive a disproportionate share of refugees because of their geographical location.

A woman holds her baby as young girls wash the dishes in Moria refugee camp on the Greek island of Lesbos in March 2019. Photo: NTB/Scanpix (Aris Messinis / AFP)

In recent years, this has changed dramatically. The growing support for immigration-critical parties has frightened many governments into using all available means to limit immigration to their country as much as possible. In addition, the EU fears a new flow of refugees such as the one it experienced in 2015 and wants to deter them from travelling by signalling that anyone arriving in Greece should expect to stay in Greece.

Even before the recent influx, Greece was among the European countries with the least capacity to handle large numbers of asylum seekers. In 2010, most EU countries halted the return of asylum seekers to Greece after the European Court of Justice ruled that conditions there violated human rights. But in 2016, the EU Commission concluded that it was prudent to gradually resume returns because the EU had contributed significantly to strengthening the asylum system – in the face of strong protests from Greece.

Greece is still struggling with the aftermath of its financial crisis, and the large increase in the number of asylum seekers means that its reception capacity is at breaking point. Asylum applications often take several years to process, while asylum seekers live under reprehensible conditions in reception centres, especially on the Greek islands.

A woman comforts her injured son on a beach shortly after they arrived with other migrants and refugees on the Greek island of Lesbos in 2016. Photo: NTB/Scanpix (Markus Heine/Nurphoto/REX)

A woman comforts her injured son on a beach shortly after they arrived with other migrants and refugees on the Greek island of Lesbos in 2016. Photo: NTB/Scanpix (Markus Heine/Nurphoto/REX)

A child wrapped in a survival blanket on the Greek island of Lesbos after having crossed the Aegean Sea from Turkey in 2016. Photo: NTB/Scanpix (Markus Heine/Nurphoto/REX)

A child wrapped in a survival blanket on the Greek island of Lesbos after having crossed the Aegean Sea from Turkey in 2016. Photo: NTB/Scanpix (Markus Heine/Nurphoto/REX)

A woman holds her baby as young girls wash the dishes in Moria refugee camp on the Greek island of Lesbos in March 2019. Photo: NTB/Scanpix (Aris Messinis / AFP)

A woman holds her baby as young girls wash the dishes in Moria refugee camp on the Greek island of Lesbos in March 2019. Photo: NTB/Scanpix (Aris Messinis / AFP)

Poorly allocated responsibilities produce dangerous consequences

If the Dublin cooperation is to survive, a proper division of responsibility must be put in place. The EU itself has acknowledged this, and member states have been negotiating for some time to arrive at such an arrangement. These negotiations have now reached a deadlock.

In particular, Hungary, Poland and other Eastern European countries are opposed to receiving refugees. The EU has put great pressure on these countries without success. Hungary’s Prime Minister, Viktor Orbán, presents himself as the protector of Christian Europe and is particularly critical of accepting Muslim refugees. The EU elections in 2019 showed that Orbán and his extreme policies have the support of the majority of the country’s population.

People demonstrate on the Sicilian port of Catania against Italian authorities’ refusal of letting 150 migrants on the Coast Guard "Diciotti" vessel disembark in August 2018. The refugees were disembarked after ten days standoff and political crisis. Photo: NTB/Scanpix (Alessio Mamo/redux)

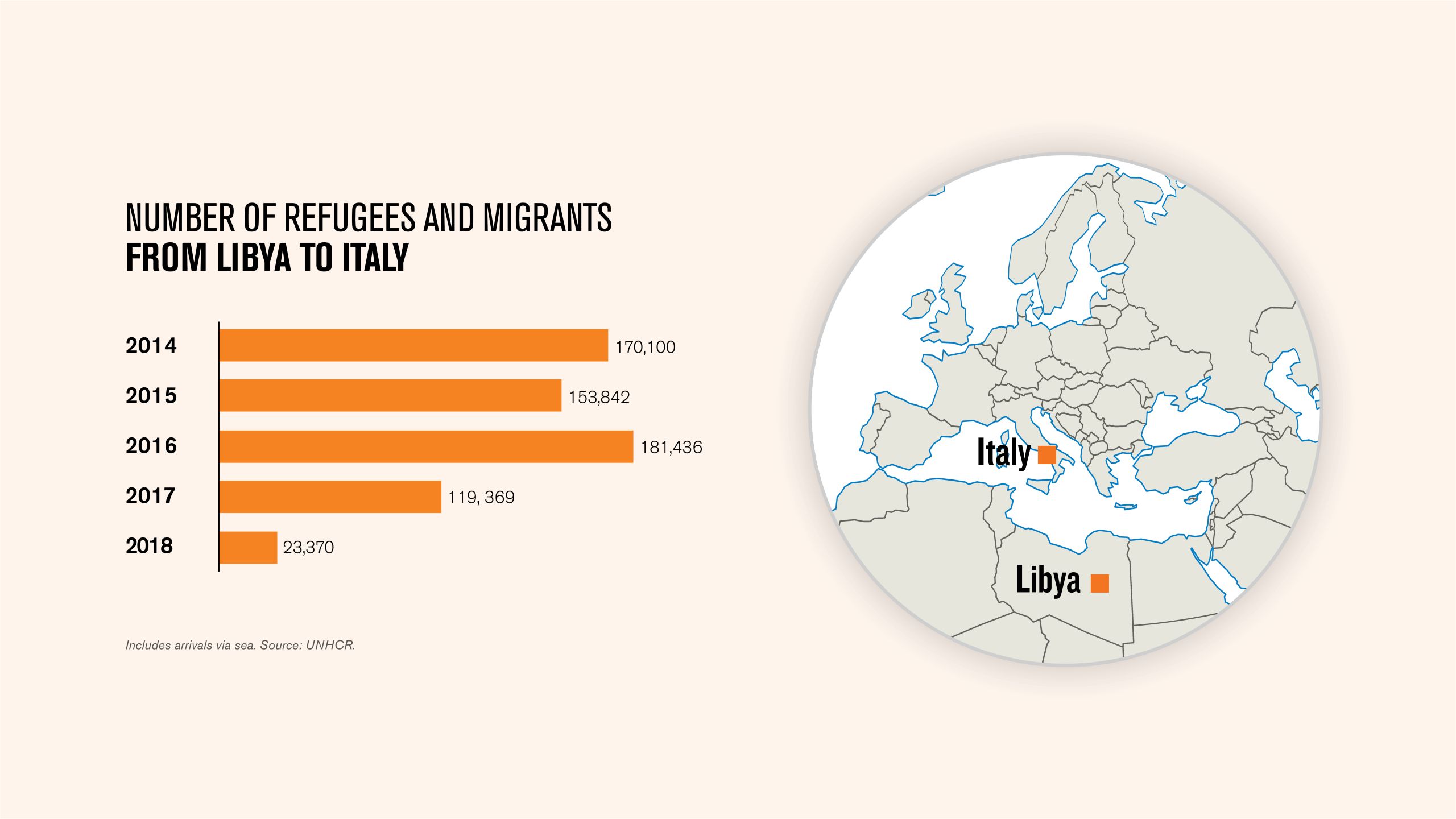

Italy has welcomed hundreds of thousands of refugees and migrants in recent years, and is, next to Greece, the country that has seen the greatest effects of Europe’s lack of will to share responsibly. The large number of refugees and migrants that Italy is expected to take care of has contributed to a growing support for political parties critical of immigration, and led to Matteo Salvini becoming the country’s Minister of the Interior and Deputy Prime Minister in June 2018. He has used his position to limit immigration to the country by all means possible.

Refugees and migrants arriving in Trapani, western Sicily on 23 April 2018. Photo: NTB/Scanpix (EPA/Christophe Petit Tesson)

Italy, which the European Court of Human Rights previously ruled had violated human rights by returning migrants to Libya, now pays the Libyan coastguard to pick up boat refugees in the Mediterranean and return them to slave-like detention camps. In the past year, ships that have rescued refugees and migrants from drowning have been denied docking in Italy until other countries have committed to accept them. Other boats have had to travel to Spain to land refugees. Now Salvini is threatening volunteer organisations with hefty fines if they defy the ban.

A wooden boat used by 450 refugees and migrants, mostly from Eritrea, remains abandoned off the Libyan coast after they were rescued by Spanish aid workers 34 miles north of Kasr-El-Karabulli, Libya, in January 2018. Photo: NTB/Scanpix (AP Photo/Santi Palacios)

These dramatic measures reduced the number of refugees and migrants coming to Italy in 2018 to 23,400 – a decline of over 80 per cent from the previous year. The decline has continued in 2019, with fewer than 2,000 refugees and migrants arriving in the first five months of the year.

People demonstrate on the Sicilian port of Catania against Italian authorities’ refusal of letting 150 migrants on the Coast Guard "Diciotti" vessel disembark in August 2018. The refugees were disembarked after ten days standoff and political crisis. Photo: NTB/Scanpix (Alessio Mamo/redux)

People demonstrate on the Sicilian port of Catania against Italian authorities’ refusal of letting 150 migrants on the Coast Guard "Diciotti" vessel disembark in August 2018. The refugees were disembarked after ten days standoff and political crisis. Photo: NTB/Scanpix (Alessio Mamo/redux)

Refugees and migrants arriving in Trapani, western Sicily on 23 April 2018. Photo: NTB/Scanpix (EPA/Christophe Petit Tesson)

Refugees and migrants arriving in Trapani, western Sicily on 23 April 2018. Photo: NTB/Scanpix (EPA/Christophe Petit Tesson)

A wooden boat used by 450 refugees and migrants, mostly from Eritrea, remains abandoned off the Libyan coast after they were rescued by Spanish aid workers 34 miles north of Kasr-El-Karabulli, Libya, in January 2018. Photo: NTB/Scanpix (AP Photo/Santi Palacios)

A wooden boat used by 450 refugees and migrants, mostly from Eritrea, remains abandoned off the Libyan coast after they were rescued by Spanish aid workers 34 miles north of Kasr-El-Karabulli, Libya, in January 2018. Photo: NTB/Scanpix (AP Photo/Santi Palacios)

People smugglers are choosing new routes

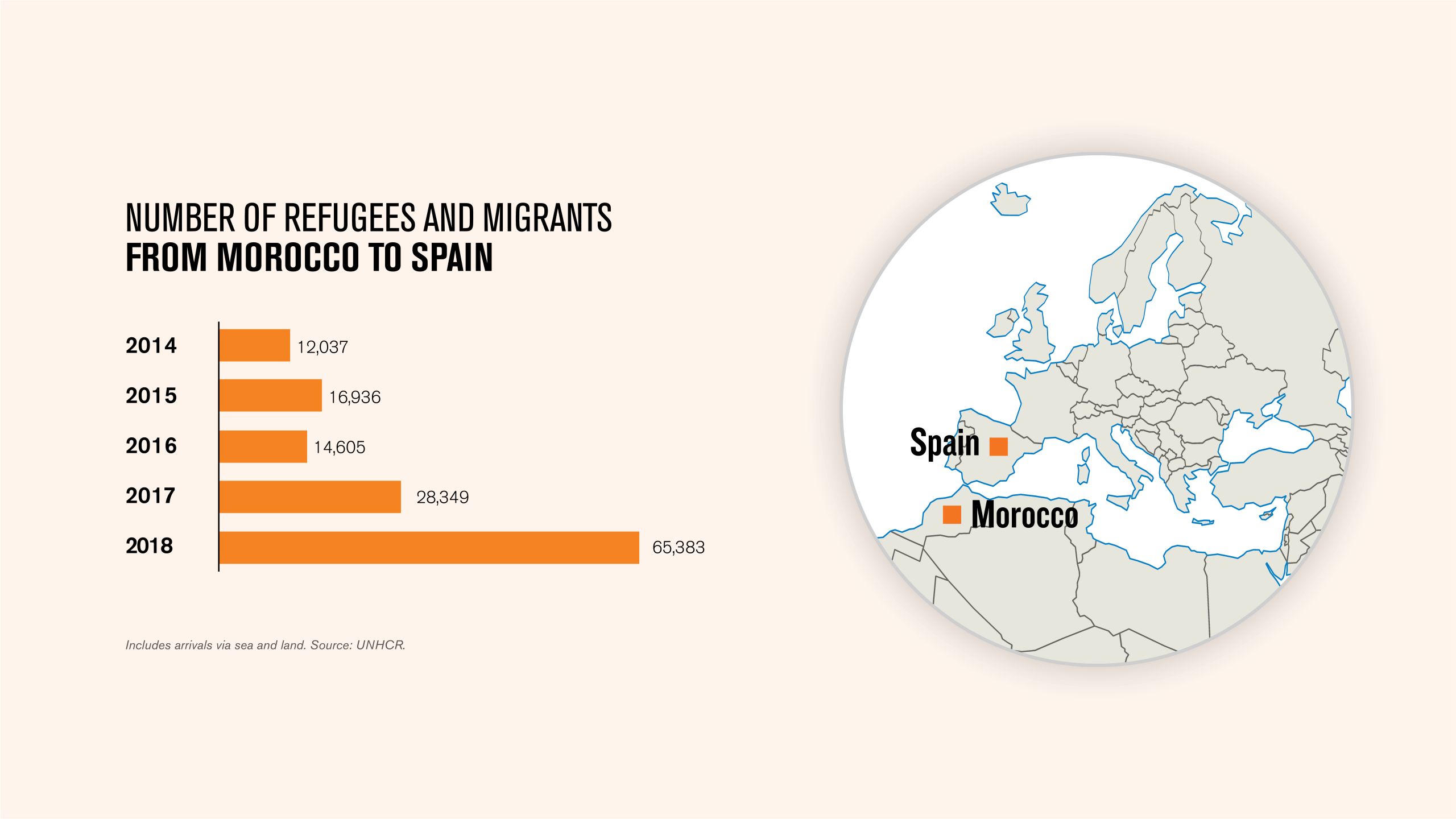

Since it has become more difficult to use the eastern and central Mediterranean routes, the western route from Morocco to Spain has become increasingly important, and in 2018 more than 50,000 refugees and migrants managed to make their way to Spain. Most of these came by sea, but there were also 18,000 who crossed the high border fences around the Spanish enclaves of Ceuta and Mellilla, located on the coast of Morocco.

Three men who were rescued from a dinghy in the Mediterranean Sea disembark from a rescue boat after their arrival at Port of Malaga, Spain, in 2018. Photo: NTB/Scanpix (Jesus Merida/Sopa Images/REX)

Spain saw a sharp increase in the number of asylum applications in 2018, but over half of the asylum seekers came from countries in Latin America and generally arrived by routes other than the Mediterranean. This suggests that those arriving in Spain via the western Mediterranean route are more able to move on to other European countries than is the case for those arriving in Italy and Greece. In addition, a significant number of people do not seek asylum, but instead look for work in the large informal labour market in Spain, particularly in the agriculture industry.

A woman is helped by a member of Spanish Red Cross after having arrived in Malaga, Spain, in May 2019. Photo: NTB/Scanpix (Jesus Merida/SOPA Images/REX)

In total, there were 24 per cent fewer people who journeyed over the Mediterranean in 2018 compared with 2017, and 84 per cent fewer than in 2015. The proportion of people losing their lives during the crossing has gone up because they have been forced to choose more dangerous routes, and the Libyan coastguard, which is now patrolling the coast, lacks the rescue skills of European rescue services. A total of seven percent of all those travelling over the Mediterranean lost their lives in 2018.

Three men who were rescued from a dinghy in the Mediterranean Sea disembark from a rescue boat after their arrival at Port of Malaga, Spain, in 2018. Photo: NTB/Scanpix (Jesus Merida/Sopa Images/REX)

Three men who were rescued from a dinghy in the Mediterranean Sea disembark from a rescue boat after their arrival at Port of Malaga, Spain, in 2018. Photo: NTB/Scanpix (Jesus Merida/Sopa Images/REX)

A woman is helped by a member of Spanish Red Cross after having arrived in Malaga, Spain, in May 2019. Photo: NTB/Scanpix (Jesus Merida/SOPA Images/REX)

A woman is helped by a member of Spanish Red Cross after having arrived in Malaga, Spain, in May 2019. Photo: NTB/Scanpix (Jesus Merida/SOPA Images/REX)

Many are still seeking asylum in Europe

Despite the fact that in 2018 only 117,000 refugees and migrants crossed the Mediterranean, over 580,000 applied for asylum in the EU, a decrease of just 11 per cent from the previous year. This shows that people smugglers are finding new ways to enter Europe when other routes are closed. Although the figures for 2018 are half of what they were in 2015 and 2016, they are still much higher than the pre-2015 norm.

A young refugee waits to be registered in Moria refugee camp on the Greek island of Lesbos on 10 January 2016. Photo: NTB/Scanpix (Bartek Langer/Nurphoto/REX)

The vast majority of those seeking asylum in Europe do not come across the Mediterranean. There is no complete overview of how these people get to Europe. An increasing number from Venezuela and other Latin American countries have been seeking asylum in Europe in recent years, and most don’t need to apply for a visa. Nevertheless, it seems that most people who arrived in 2018 either crossed at regular border stations with false papers or managed to cross the border into the Schengen Area without being registered.

A young girl holds a puppy inside the official refugee camp of Moria on the Greek island of Lesbos, on March 20, 2019. Photo: NTB/Scanpix (Aris Messinis / AFP)

Germany received 162,000 asylum seekers in 2018 and remains the country in Europe that has taken in the highest number of refugees and migrants, despite a decline from the previous year. France had a slight increase from 2017, receiving 110,000. Greece, Spain and Italy had the next highest intakes. Cyprus and Spain had the largest increases from 2017, with rises of 70 and 60 per cent respectively. Italy and Austria had the largest declines: 61 and 49 per cent respectively.

Eritrean and Syrian refugees depart from Rome Ciampino airport for Sweden and Finland on 21 October 2015. Photo: NTB/Scanpix (Agf/REX)

Sweden, which received the second highest number of refugees and migrants in Europe during the 2015 influx, has subsequently seen a significant decline, receiving just 18,000 asylum seekers in 2018. This is due both to restrictions on the rights of asylum seekers and to the fact that border controls have made it more difficult for people to move north in Europe. Nevertheless, Sweden continues to accept far more than the other Nordic countries combined. Norway received only 2,655 asylum seekers in 2018, the lowest number since the mid-1990s.

A young refugee waits to be registered in Moria refugee camp on the Greek island of Lesbos on 10 January 2016. Photo: NTB/Scanpix (Bartek Langer/Nurphoto/REX)

A young refugee waits to be registered in Moria refugee camp on the Greek island of Lesbos on 10 January 2016. Photo: NTB/Scanpix (Bartek Langer/Nurphoto/REX)

A young girl holds a puppy inside the official refugee camp of Moria on the Greek island of Lesbos, on March 20, 2019. Photo: NTB/Scanpix (Aris Messinis / AFP)

A young girl holds a puppy inside the official refugee camp of Moria on the Greek island of Lesbos, on March 20, 2019. Photo: NTB/Scanpix (Aris Messinis / AFP)

Eritrean and Syrian refugees depart from Rome Ciampino airport for Sweden and Finland on 21 October 2015. Photo: NTB/Scanpix (Agf/REX)

Eritrean and Syrian refugees depart from Rome Ciampino airport for Sweden and Finland on 21 October 2015. Photo: NTB/Scanpix (Agf/REX)

A paradigm shift in refugee policy

In the wake of the migrant crisis in 2015, deep contradictions have arisen, both internally within individual countries and between EU countries, and there is major disagreement on how to handle the increased influx of refugees and migrants. Opposition to receiving refugees is particularly strong in Eastern European countries.

In many Western European countries, resistance to immigration has also increased, and political parties critical of immigration have grown in popularity. After the European Parliament elections, the National Rally (Rassemblement national) became France’s largest party, and in both Italy and Austria, strongly immigration-critical parties are part of the government coalition.

The most important change, however, is that the established parties near the centre have gradually changed their policies and have adopted political solutions that they themselves rejected only a few years ago. This has been most pronounced in Denmark, where the Social Democrats joined forces with the conservative government in 2019 and adopted a new immigration law that has been called a “paradigm shift”. This states that refugees who come to Denmark should, as a rule, return to their home country as soon as it is safe. The Social Democrats are thus placing less emphasis on integration than before, and the financial support for refugees has been renamed from “integration support” to “repatriation support”.

The most controversial aspect of the new law is that resettlement refugees (quota refugees) should also be sent back to their home country. No country has done this before, and it violates the principle of the refugee resettlement scheme, which is designed for refugees in need of permanent resettlement in a new country. The proposal received strong criticism from the UN High Commissioner for Refugees, but was adopted nevertheless.

In the 2019 Danish parliamentary elections on 5 June, the “red bloc” won, and there is great excitement for the upcoming government negotiations since all the smaller parties on the red-green side are opposed to the tightening of immigration policy. The Social Democrats, however, are threatening to force new elections if they don’t receive support for the main lines of their policy.

Limiting the right to seek asylum

Mette Frederiksen, leader of the Social Democrats, has signalled that she wants to make it impossible to seek asylum in Denmark in the future. Instead, she wants to increase support for refugees in the areas closer to their homeland, and wants to send refugees who come to Denmark to reception centres in partner countries in Africa and Asia. Refugees who come to Denmark must be selected as resettlement refugees. Denmark accepted zero resettlement refugees in 2018.

The Norwegian Labour Party has been inspired by its Danish sister party, and adopted a new migration and integration policy at their national party conference in 2019. The party wants to limit the number of individual asylum applications as much as possible, prioritising resettlement refugees instead, while reallocating more money to help refugees near to their home country by means of a “solidarity pot”. They want to negotiate agreements with so-called “safe third countries” through which refugees travel on their way to Europe, and send the asylum seekers back there.

The EU-Turkey agreement has only partially worked as intended, and returning asylum seekers to Turkey has been far more difficult than anticipated. Nevertheless, the EU regards it as a success, since new arrivals in Greece have been reduced by more than 90 per cent. As a result, leading European politicians, such as Angela Merkel and Emmanuel Macron, hope to negotiate similar agreements with other countries outside Europe.

In February 2019, the EU and the Arab League met in Egypt to discuss, among other things, increased cooperation on refugees and migration. The EU hoped to get countries such as Egypt, Tunisia and Morocco to agree on a deal, but the proposal received a lukewarm reception. Also, the African Union was highly critical of the idea that African countries should accept refugees who have been sent back from Europe in addition to all the refugees they already accommodate.

It is very unclear how the EU envisages that such agreements should be designed so as not to break its obligations under international conventions, especially since many of the relevant partner countries have not signed the Refugee Convention. Neither have the EU’s wishes been met with much understanding in large host countries such as Lebanon, which feels somewhat abandoned after receiving over 1.5 million Syrian refugees.

Picture in the background:

Chairman Mette Fredriksen of the Social Democrats in Denmark, presents the immigration proposal. Photo: NTB/Scanpix (Mads Claus Rasmussen/Ritzau Scanpix).

The EU’s headache

The background to the change in policy of established European political parties is twofold. Firstly, they are seeing an increasing scepticism among parts of the population towards what is perceived as uncontrolled immigration. They fear that voters will turn to the immigration-critical parties if they fail to show that they are taking their concerns seriously.

Secondly, there has been a growing concern in many parties that previous asylum policy has had dramatic humanitarian consequences. Several thousand refugees and migrants die each year in their attempt to cross the Mediterranean, and probably even more die before they come that far. People who want to seek protection in Europe are at the mercy of cynical and often brutal people smugglers, and European politicians know that people smuggling is an inevitable consequence of the policies they themselves have adopted.

Everyone has the right to seek asylum when they arrive in Europe, but by refusing a visa to those who might seek asylum and punishing airlines and ferries that take passengers without a visa, the authorities ensure that all legitimate ways to enter Europe are closed to most potential asylum seekers. It is a serious paradox that Europe’s refugee policy assumes that it is so dangerous and difficult to seek asylum that sufficiently few people take the chance to do so. History has also shown that as soon as a smuggling route is established that can transport large numbers of people to Europe, measures are taken to increase the risk and cost of travelling so that fewer people choose to do so.

While most European politicians acknowledge the weaknesses of the existing refugee policy, it has proved very difficult to agree on an alternative that is both in line with international conventions and able to gain sufficient political support. Very few consider it realistic to remove the visa requirement for refugees who wish to seek asylum in Europe, because it will lead to a higher number of arrivals than the countries are able to handle. Nor do the majority consider it realistic to remove the measures that have been implemented to prevent refugees and migrants from reaching Europe, following the experiences of 2015.

Consequently, they are continuing a policy that is making it increasingly dangerous and ever more expensive to seek protection in Europe. All while the market for people smugglers, which everyone claims they want to fight, will continue to grow.

Picture in the background:

A girl poses for a photo during a demonstration against the EU-Turkey deal in Athens on 17 March 2018. Photo: NTB/Scanpix (AP photo/Yorgos Karahalis, File).